Shadow Banking in a Crisis: Evidence from Fintech During COVID-19

We evaluate the performance of Chinese fintech and bank credit providers during COVID-19. Comparing samples of fintech and bank loan records across the pandemic outbreak, we find that fintech companies are more likely to expand credit access to new and financially constrained borrowers after the start of the pandemic. However, the delinquency rate of fintech loans triples after the outbreak, but there is no significant change in the delinquency rate of bank loans. These results shed light on the benefits of shadow banking in a crisis and hint at the potential fragility of such institutions when delinquency rates spike.

China has developed one of the largest shadow banking industries in the form of fintech lending. Thousands of fintech lenders have mushroomed since 2017, but their rapid development was severely affected by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite their importance in the lending market, there is little empirical research that evaluates the performance of these shadow banks in a crisis. We fill this gap by comparing the performance of Chinese fintech lenders with traditional banks before and after the start of the pandemic. Specifically, we collect loan records from three leading fintech lenders and a state-owned commercial bank to evaluate the quantity and quality of loans provided by these two types of credit providers.

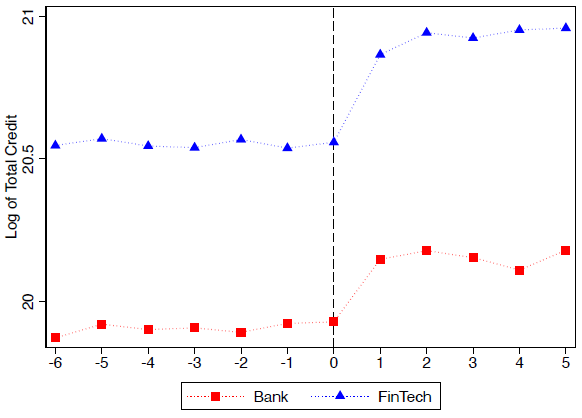

We first study the quantity of loans provided by fintech companies and banks, following Fisman, Paravisini, and Vig (2017) and Di Maggio and Yao (2020). We begin the analysis by showing the (unconditional) new credit access before and after the pandemic outbreak for fintech and bank loans. The horizontal axis of Figure 1 measures time (in a month) relative to the outbreak of COVID-19 in China in January 2020. The event time t = 0 represents the month when COVID-19 was first identified in the country, and the negative and positive numbers represent the months before and after the outbreak, respectively. We take the log of the total new credit issued by the fintech companies and the bank and observe that the size of new credit granted by both the fintech companies and the bank surges after the start of the pandemic, though the increase in loans is higher for fintech providers.

Figure 1: Log of total credit issued by fintech and banks

Notes: This figure takes the log of the total new credit issued by the fintech companies and the bank before and after the outbreak of COVID-19. The sample period is 2019:07 to 2020:06. The horizontal axis displays event time, in months, where t = 0 corresponds to 2020:01 when the disease was first identified in China.

In more detailed analyses, we find that the beneficiaries of the extra credit access vary between the fintech companies and the bank. The expansion in the credit provided by the bank is largely enjoyed by preexisting borrowers, while the increase in the fintech credit is shared between new and preexisting borrowers. Furthermore, the percentage of new users rises for the fintech companies but declines for the bank after the pandemic outbreak. We also partition the new users according to their income level and find that the proportion of low-income users elevates in the fintech sample, which is opposite to the bank. We further discover that fintech companies are more likely to provide credit to borrowers who are financially constrained and those who reside in places with higher infection rates during the pandemic. These results indicate that the fintech industry outperforms banks in providing credit to those who need it most during the unexpected health crisis.

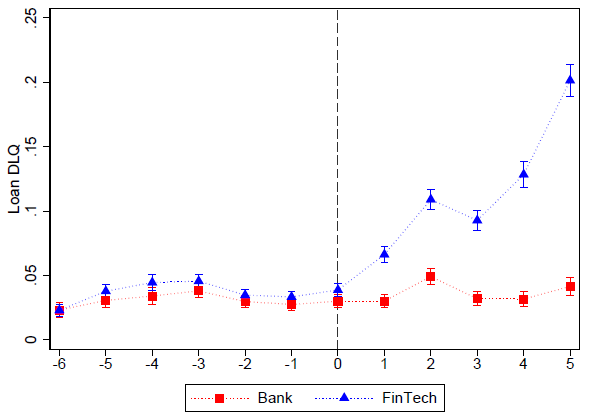

We then expand the focus on the quality of loans granted by these two types of financial intermediaries before and after the pandemic outbreak. We study the quality of loans using the delinquency rate, defined as the number of borrowers who breached their financial commitments over the total number of borrowers, following Dobbie et al. (2020) and Hertzberg, Liberti, and Paravisini (2010).

Figure 2 is analogous to Figure 1, except here we plot the delinquency rates for fintech and bank lenders before and after the pandemic outbreak. Before the pandemic, both fintech and bank loans have a similar delinquency rate between 2% and 5%, and there is no statistical difference for each monthly pairwise comparison. After the outbreak, the rate for bank loans stays at the same level, while the rate for fintech loans jumps up sharply and becomes significantly higher than the rate for bank loans. Remarkably, five months after the outbreak, the delinquency rate for fintech loans exceeds 20%, but the rate remains at 4% for bank loans; such a difference is significant in both statistical and economic senses. Our data reveal that while fintech and bank loans have similar delinquency rates before the pandemic, there is a dramatic increase in the rate for the fintech companies, but not for the bank during the periods of instability.

Figure 2: Delinquency rate for bank and fintech loans before and after COVID-19

Notes: This figure plots average values of the delinquency rate for both bank and fintech loans before and after COVID-19 with the 95% confidence interval. The sample period is 2019:07 to 2020:06. The horizontal axis displays event time in months, where t = 0 corresponds to 2020:01 (the start of the pandemic).

We then perform additional tests to show that preexisting differences in borrower characteristics do not purely drive the differences in the performances between these two types of credit providers. Interestingly, the sharp increase in fintech loan delinquency rates cannot be fully explained by the presence of first-time borrowers (as opposed to those who had credit records before the observation window) or the severity of the pandemic in borrowers’ residential cities. Fintech loans are more susceptible to moral hazard, as we find that borrowers holding both loan types prioritize the payment of bank loans. Additionally, we note that the interest rate is a good predictor of the delinquency probability for both loan types before the outbreak, but such predictability perishes for fintech loans after the outbreak. This set of results reveals the potential challenge of maintaining a sustainable delinquency rate for the fintech industry during the pandemic.

To conclude, we find that fintech companies are more likely to expand credit access to new and financially constrained borrowers after the start of the pandemic. However, this increased credit provision may not be sustainable; the delinquency rate of fintech loans triples after the outbreak, but there is no significant change in the delinquency of bank loans. These results shed light on the benefits of shadow banking in a crisis and hint at the potential fragility of such institutions when delinquency rates spike. We contribute to the literature on the regulation of financial innovation. Despite the radical changes in the regulatory regime for the fintech lending industry in China, little empirical evidence informs these amendments of regulations. We first document the strengths and weaknesses of the Chinese fintech industry to advise policymakers. Interested readers are referred to our academic publication for the complete results and discussions.

(Zhengyang Bao, Department of Finance at School of Economics and Wang Yanan Institute for Studies in Economics, Xiamen University; Difang Huang, Department of Econometrics and Business Statistics, Monash Business School.)

References

Bao, Zhengyang, and Difang Huang. “Shadow Banking in a Crisis: Evidence from Fintech During COVID-19.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis (forthcoming). https://jfqa.org/2021/06/16/shadow-banking-in-a-crisis-evidence-from-fintech-during-covid-19/.

Di Maggio, Marco, and Vincent W. Yao. 2020. “Fintech Borrowers: Lax Screening or Cream-Skimming?” Review of Financial Studies. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhaa142.

Dobbie, Will, Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham, Neale Mahoney, and Jae Song. 2020. “Bad Credit, No Problem? Credit and Labor Market Consequences of Bad Credit Reports.” Journal of Finance 75 (5): 2377–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12954.

Fisman, Raymond, Daniel Paravisini, and Vikrant Vig. 2017. “Cultural Proximity and Loan Outcomes.” American Economic Review 107 (2): 457–92. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20120942.

Hertzberg, Andrew, Jose Maria Liberti, and Daniel Paravisini. 2010. “Information and Incentives Inside the Firm: Evidence from Loan Officer Rotation.” Journal of Finance 65 (3): 795–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01553.x.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email