“I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For”: Evidence of Directed Search from a Field Experiment

We explore the impact of wage offers on job applications, testing implications of the directed search model and trying to distinguish it from random search. We use a field experiment conducted on an online Chinese job board, with real jobs for which we randomly varied the wage offers across three ranges. We find that higher wage offers raise application rates overall, which is consistent with directed search, but can also arise with random search. We also find that higher wage offers raise application rates for job seekers with wage offers above reservation wages, and that—among the latter—the increase in application rates is stronger for those with higher reservation wages. The latter two types of evidence are consistent with directed search but not random search. Hence, our evidence lends support to directed search models.

Existing models of the labor market in the search and matching literature often describe a specific way in which workers search for jobs and employers attract workers, i.e., either random search or directed search. Random search models assume that job seekers and employers meet exogenously and at random (e.g., Diamond 1982; Mortensen 1982, 1986; Pissarides 1985). Whether a meeting results in a hire, and at what wage (and/or other terms of trade), is endogenously determined by post-meeting bargaining. As a consequence, changing these terms has no influence on attracting workers to jobs. In contrast, models of directed search (also known as competitive search) assume that agents target their search toward particular counterparts based on the terms posted, and therefore these terms, such as higher wages, influence who meets whom (e.g., see Wright et al. 2021 for a review). The nearly mutually exclusive assumptions of these two types of models lead to different predictions for market efficiency and the effectiveness of certain labor market policies.

Researchers tend to choose random or directed search for analytical convenience (although theoretical implications can differ), rather than basing their work on the best characterization of job seekers’ behavior. In labor markets with informational frictions, job seekers’ search behavior may involve both randomness, such as which job ads to open, and direction, such as which job ads to apply to conditional on opening them. Thus, the question is not so much whether the evidence is completely consistent with one model or the other, but which model provides a better characterization of job seekers’ behavior—and, in particular, whether there is evidence that the random search assumption is too simple and we therefore must allow for directed search.

In recent years, some studies tried to test empirically which type of model best characterizes job seekers’ behavior by looking at the relationship between offered wage and job application. The prediction that is derived from directed search models with heterogeneous firms (e.g., in terms of productivity or technology, hence offering different wages) but homogeneous workers (e.g., in terms of reservation wage or quality) is that holding other things equal, the number of applications firms receive should (not) vary with the wage offered—consistent with directed search (random search) (Moen 1997). The studies based on observational data (Faberman and Menzio 2018, Banfi and Villena-Roldán 2019, Marinescu and Wolthoff 2020) face the challenge that variation in wages tends to be correlated with other features of jobs, generating potential bias; and the studies based on field experiments (Dal Bo et al. 2013, Deserranno 2019, Hedblom et al. 2019, Abebe et al. 2021) tend to ignore the role of reservation wages that tend to generate spurious evidence in favor of directed search, i.e. if job seekers use random search but only apply for jobs with offered wages higher than their reservation wages, one will still find evidence of more applications when offered wages are higher. Belot et al. (2018) is the only other study of which we are aware that tries to address both of these issues in testing for directed search. Although innovative, their research design may encounter a potential threat to external validity, sample selection bias, and an experimenter demand effect.

In a recent paper, we try to address these challenges and contribute new evidence to this question by conducting a large-scale natural field experiment. We generate random variation across job seekers in invitations to apply for jobs that differ in terms of wage offers, in three ranges: High (20,000-25,000 CNY), Medium (15,000-20,000 CNY), and Low (10,000-15,000 CNY). The experimental data allow the estimation of application responses for job ads that are otherwise identical, free from the potential bias that can arise in observational data when wage variation is correlated with other job characteristics. We also use the current/most recent wage from job seekers’ resumes as a proxy for their reservation wage for accepting a new job. Combining these data allows the estimation of application responses to exogenous wage variation that is above the job seekers’ reservation wages, which is important for distinguishing between random and directed search.

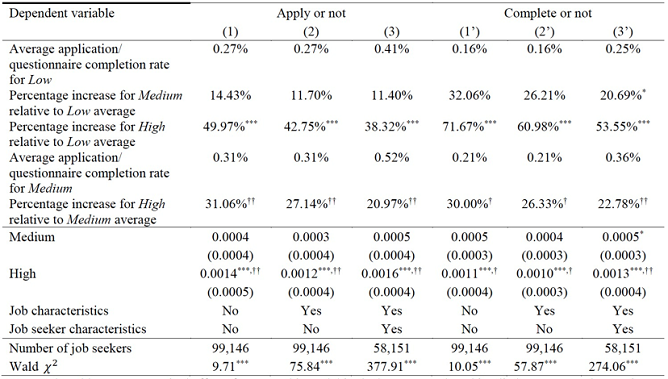

Our analysis proceeds in three steps. First, we follow the common practice in existing empirical studies of testing whether higher wage offers attract more applications. Table 1 reports the differential effects of the wage offers on application and a more intensive measure of questionnaire completion decisions, with Low wage as the reference group. The percentage changes in the application or completion rate (reported in the top panel), implied from the probit model estimates (reported in the bottom panel), relative to the comparison groups, show that job seekers are more likely to apply for higher wage jobs, in line with most previous empirical studies. This evidence could be more consistent with direct search than random search. However, an affirmative answer to this question alone—without considering reservation wages—cannot provide decisive evidence of directed search.

Table 1. Random search vs. directed search

Notes: The table reports marginal effects from a probit model in the bottom panel, and implied percentage changes in the upper panel. The dependent variable is indicated in column headings. The sample includes only sampled job seekers who were sent job ad emails and app messages. All applications made to job positions other than those applicants were sent are excluded. Job characteristics include job flexibility and job position dummy variables, and job seeker characteristics include gender, marital status, age and its square, highest educational degree in category, years of work experience and its square, overseas work/study experience, current work status, job tenure and its square, Beijing Hukou, type of job sought (full-timne, part-time, or intern), and expect to work in Beijing. Job seekers with missing or inconsistent data on individual characteristics are excluded. Robust standard errors allowing for heteroskedasticity are reported in parentheses. The * symbols attached to Medium and High wage variables in the lower panel and to percentage increase in the upper panel are for the statistical significance of the High and Medium relative to Low estimates, and the † symbols are for the statistical significance of the High relative to the Medium estimates. Three, two, or one symbols indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level, respectively. Wald-statistic is for Wald test of joint significance of all regressors.

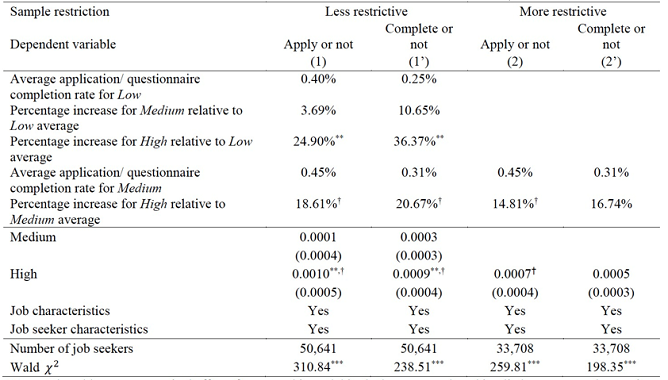

Second, we examine whether higher wage offers attract more job applications when wage offers are always above reservation wages. By restricting the sample to the job seekers with reservation wages capped at the upper limit of the Low wage offer range (i.e., 15,000 CNY), we eliminate the possibility that the number of applications increases with higher wages because the share of job seekers for whom the offered wage exceeds the reservation wage increases. Table 2 shows that job seekers are still more likely to apply for higher wage jobs even when the offered wage variation is always above their reservation wages. This provides more definitive evidence in favor of directed search.

Table 2. Random search vs. directed search conditional on reservation wage no more than 15,000 CNY

Notes: The table reports marginal etiects trom a probit model in the bottom panel, and implied percentage changes in the top panel. The sample restriction and dependent variable are indicated in column headings. The RW is measured by the current/most recent wage. The sample in all models is restricted to sampled job seekers who had RW no more than 15,000 CNY. In addition, the “less restrictive” sample includes sampled job seekers who were sent Low, Medium, or High wage offers, whereas the “more restrictive” sample only includes sampled job seckers who were sent Medum or High wage offers. All models include control variables for job and job seeker characteristics as in columns (3) and (3’) of Table 2. See also notes to Table 2.

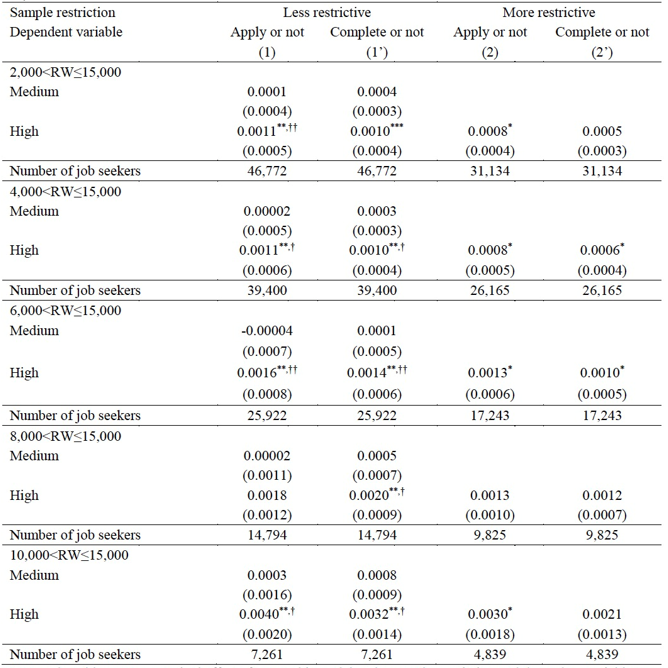

Third, we test whether, among the job seekers with wage offers always above their reservation wages, the response to wage offers varies with the reservation wage. The prediction of directed search models with heterogeneous firms and heterogeneous workers is that job seekers direct their search effort to a particular (sub)market where employers post wage offers specifically to attract them (Shi 2002; Menzio et al. 2016). We assume that higher-quality job seekers have higher reservation wages, so that the probability of getting a job, conditional on the same wage offer, should increase with the reservation wage, and hence the response to higher offered wages should be stronger for those with higher reservation wages. Table 3 indicates that as we raise the lower reservation wage cutoff from 2,001 to 10,001 CNY, the treatment effects (especially the effects of High wage offers) become stronger in both magnitude and statistical significance. Thus, this final analysis addresses how search responds to competition, and provides additional evidence in favor of directed search over random search by confirming the above assumptions.

Table 3. Random search vs. directed search by RW range conditional on reservation wage no more than 15,000 CNY

Notes: The table reports marginal effects from probit models. The sample restriction and dependent variable are indicated in colum headings. The RW is measured by the curren/most recent wage. The sample in all models is restricted to sampled job seekers who had RW no more than 15,000 CNY. In addition, the “less restrictive” sample includes sampled job seekers who were sent Low, Medium, or High wage offers, whereas the “more restrictive” sample only includes sampled job seekers who were sent Medium or High wage offers. Each panel from the top to the bottiom increases the RW lower limit. All models include control variables for job and job seeker characteristics as in columns (3) and (3’) of Table 2. See also notes to Table 2.

Taken together, our findings provide evidence in favor of directed search over random search. Our findings are consistent with evidence from labor markets in the US (Marinescu and Wolthoff 2020, Hedblom et al. 2019), Edinburgh (Belot et al. 2018), Mexico (Dal Bo et al. 2013), Chile (Banfi and Villena-Roldán 2019), Uganda (Deserranno 2019), and Ethiopia (Abebe et al. 2021). This suggests that directed search is a phenomenon that exists in many labor markets, and in many economies at varying levels of development.

(Haoran He is Professor of Economics and Co-Director of the Center for Game Theory Decision and Behavior at Beijing Normal University; David Neumark is Distinguished Professor of Economics and Co-Director of the Center for Population, Inequality, and Policy at UCI; Qian Weng is an Associate Professor in the School of Labor and Human Resources at Renmin University of China.)

References

Abebe, Girum, A. Stefano Caria, and Esteban Ortiz-Ospina. 2021. “The Selection of Talent: Experimental and Structural Evidence from Ethiopia.” American Economic Review 111 (6): 1757–1806. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20190586.

Banfi, Stefano, and Benjamin Villena-Roldán. 2019. “Do High-Wage Jobs Attract More Applicants? Directed Search Evidence from the Online Labor Market.” Journal of Labor Economics 37 (3): 715–46. https://doi.org/10.1086/702627.

Belot, Michele, Philipp Kircher, and Paul Muller. 2018. “How Wage Announcements Affect Job Search—a Field Experiment.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 11814. http://ftp.iza.org/dp11814.pdf.

Dal Bo, Ernesto, Frederico Finan, and Martín A. Rossi. 2013. “Strengthening State Capabilities: The Role of Financial Incentives in the Call to Public Service.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 128 (3): 1169–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjt008.

Deserranno, Erika. 2019. “Financial Incentives as Signals: Experimental Evidence from the Recruitment of Village Promoters in Uganda.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11 (1): 277–317. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20170670.

Diamond, Peter A. 1982. “Wage Determination and Efficiency in Search Equilibrium.” Review of Economic Studies 49 (2): 217–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297271.

Faberman, R. Jason, and Guido Menzio. 2018. “Evidence on the Relationship Between Recruiting and the Starting Wage.” Labour Economics 50: 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2017.01.003.

Hedblom, Daniel, Brent R. Hickman, and John A. List. 2019. “Toward an Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility: Theory and Field Experimental Evidence.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 26222. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26222.

Marinescu, Ioana, and Ronald Wolthoff. 2020. “Opening the Black Box of the Matching Function: The Power of Words.” Journal of Labor Economics 38 (2). https://doi.org/10.1086/705903.

Menzio, Guido, Irina A. Telyukova, and Ludo Visschers. 2016. “Directed Search over the Life Cycle.” Review of Economic Dynamics 19: 38–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2015.03.002.

Moen, Espen R. 1997. “Competitive Search Equilibrium.” Journal of Political Economy 105 (2): 385–411. https://doi.org/10.1086/262077.

Mortensen, Dale T. 1982. “Property Rights and Efficiency in Mating, Racing, and Related Games.” American Economic Review 72 (5): 968–79. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1812016.

Mortensen, Dale T. 1986. “Job Search and Labor Market Analysis.” In Handbook of Labor Economics, vol. 2, edited by Orley Ashenfelter and David Card, 849–919. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Pissarides, Christopher A. 1985. “Short-Run Equilibrium Dynamics of Unemployment, Vacancies, and Real Wages.” American Economic Review 75 (4): 676–90. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1821347.

Shi, Shouyong. 2002. “A Directed Search Model of Inequality with Heterogeneous Skills and Skill-Biased Technology.” Review of Economic Studies 69 (2): 467–91. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1556739.

Wright, Randall, Philipp Kircher, Benoit Julien, and Veronica Guerrieri. 2021. “Directed Search and Competitive Search: A Guided Tour.” Journal of Economic Literature 59 (1), 90–148. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20191505.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email