The Effect of Computer-Assisted Learning on Students’ Long-Term Development

We examine the effect of computer-assisted learning on students’ long-term development. We explore the implementation of the largest ed-tech intervention in the world to date, which connected China’s best teachers to more than 100 million rural students through satellite internet. Exposure to the program improved students’ academic achievement, labor performance, and computer usage for at least ten years after program implementation. These findings indicate that education technology can have long-lasting, positive effects on a variety of outcomes and can be effective in reducing the rural-urban education gap.

In most countries, there tends to be a large gap between urban and rural education outcomes. For example, according to data by the World Inequality Database on Education, the urban secondary-education completion rate is higher than the rural completion rate by 288% in low-income countries, by 62% in lower middle-income countries, by 46% in upper middle-income countries, and by 18% in high-income countries (see Note 1).

The traditional solution intended to narrow this urban-rural gap relied on monetary subsidies to rural schools to allow them to acquire better resources, especially higher-quality teaching personnel. However, this type of program is usually unsuccessful because high-quality urban teachers are often reluctant to relocate to rural areas. In more recent years, education technology provided new and better solutions to this problem by allowing high-quality teachers in urban locations to connect with rural students through remote learning.

In China, the setting of one of our recent studies (Bianchi, Lu, and Song 2020), rural schools face a variety of challenges, including poorly qualified teachers, insufficient resources, and large classes. In 2000, only 14.3% of teachers in rural secondary schools had a bachelor’s degree, compared with 32% of teachers in urban secondary schools. Rural schools also had an average student–teacher ratio of 17.13, much higher than the 12.43 student¬–teacher ratio in urban schools. As a result, only 7.1% of students in rural middle schools enrolled in high school, while high-school enrollment was 9.4 times higher in urban schools (2000 Chinese Census).

In Bianchi, Lu, and Song (2020), we study a 2004 Chinese reform—the “Modern Distance Education Program in Rural China”—that connected high-quality teachers in urban areas with more than 100 million students in rural primary and middle schools through the use of satellite internet.

Specifically, the program was based on three separate pedagogical “modes” (Wang, Zeng, Wang 2015). First, it delivered 440,142 DVD player sets, comprising TVs and DVD players. These sets were used to play lectures and learning materials prepared by some of the best teachers in the country. Second, the program installed 264,905 satellite receiving sets, comprising satellite antennas, satellite TV equipment, computers, and other related devices. These satellite sets allowed the Chinese government to deliver new lectures and learning materials through the internet, instead of relying on physical media. Moreover, it allowed local teachers to use computers and the internet to prepare their own lectures. Third, the program built 40,858 computer classrooms, which included a network of computers and a projector. In these computer rooms, students could follow from their own device the new teaching materials prepared by the central government. Moreover, the computer rooms could be used to introduce computer science in the curriculum of receiving schools.

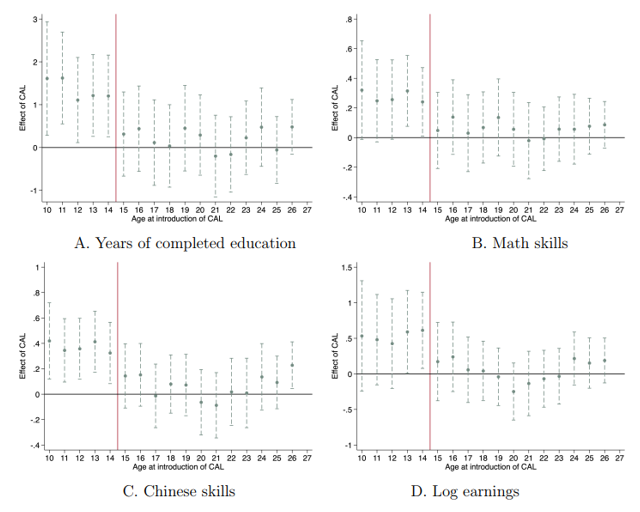

To isolate the effects of computer-assisted learning (CAL), we exploit both time and geographical variation in the implementation of the reform. Along the time dimension, we compare cohorts who were at most 14 years old at the time of the policy implementation to cohorts who were at least 15 years old. The first group attended middle school after the reform and was exposed to CAL, while the second group was either already attending a higher grade or was in the labor market when the policy went into effect. Along the geographical dimension, we instead exploit the staggered implementation in different counties across four years. The program reached 678 counties in 2004, 893 counties in 2005, 493 counties in 2006, and 380 counties in 2007. In addition, it was not implemented in 416 counties.

As a practical example of our identification strategy, we can compare education and labor outcomes between individuals born in 1990 in Jinzhai County and individuals born in the same year in Taihu County. The former group attended middle school after the policy implementation in 2004 and was exposed to CAL. In contrast, the latter group had already completed middle school when the program reached Taihu in 2006. Comparing the long-term outcomes of these two groups, however, does not isolate the effect of the program. If residents of Jinzhai, for example, tend to always complete more years of education, a single cross-county comparison could lead to biased estimates for the effect of the CAL reform. In addition to comparing outcomes along the first dimension, we can therefore compare the outcomes of individuals not exposed to the policy in either county (for example, those born in 1988). The differences in outcomes between the two groups capture cross-county variation that is constant across cohorts. By subtracting this last result from the first comparison, we can isolate the effect of CAL.

We report three key findings. The first is that exposure to the reform in middle school significantly increased students’ academic achievement in the long run. Completed education increased by 0.85 years (+9%), math skills measured at the time of the survey (seven to ten years after exposure) increased by 0.18 standard deviations (σ), and Chinese skills increased by 0.23σ (Figure 1). The second key finding is that the reform significantly improved students’ labor-market outcomes. Students who were exposed to CAL were more likely to be employed in occupations that focused on cognitive skills, instead of manual skills. They also earned, on average, 59% more than individuals living in the same county but not exposed to the new education technology. The third key finding is that the reform increased internet and computer usage by 15% several years after middle school. Overall, exposure to the policy can explain a 21% reduction in the preexisting urban–rural education gap and a 78% reduction in the preexisting earning gap.

Figure 1. Leads and Lags in the Effect of Computer-Assisted Learning (CAL)

Out of several pedagogical changes introduced by the reform, access to high-quality teachers through remote learning seems to have played the main role in increasing human capital. Unlike other components of the program, the deployment of recorded lectures was highly standardized across different geographical areas. Therefore, the lack of cross-county heterogeneity in the treatment effects is in and of itself evidence in favor of the hypothesis that access to high-quality teachers through recorded lectures was important.

Prior research on remote learning highlighted how online education requires a level of self-discipline that most students might not have (McPherson and Bacow 2015). Moreover, it might induce students to postpone studying until just before the exam, leading to suboptimal learning (Figlio, Rush, and Yin 2013). In our context, however, remote learning happened in the classroom under the direct supervision of local teachers. These implementation features limited distractions and procrastination.

Overall, the results of our recent study make three main contributions to the debate on CAL. First, they show that the effects of CAL can last for several years after the initial exposure to education technology. These findings complement existing evidence that indicates how CAL might improve test scores in the months immediately after its implementation. Second, they show that the positive effects of education technology can be tracked across different outcomes. In our setting, CAL affected education outcomes, labor-market performance, and internet usage. Third, they showed how technology can be an effective way to close the rural–urban gap in education.

As proven by the Chinese experience, technology is able to connect students in rural schools to the best teachers in the country without teacher relocation. Considering that the rural-urban gap is a phenomenon common in both developed and developing countries, these findings have important policy implications that transcend the Chinese experience.

Note 1: https://www.education-inequalities.org/

(Nicola Bianchi is an assistant professor at Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, and a faculty research fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research; Yi Lu is a professor at the School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University; Hong Song is an associate professor at the School of Economics, Fudan University.)

References

Bianchi, Nicola, Yi Lu, and Hong Song. 2020. “The Effect of Computer-Assisted Learning on Students’ Long-Term Development.” NBER Working Paper 28180. https://doi.org/10.3386/w28180.

Figlio, David, Mark Rush, and Lu Yin. 2013. “Is It Live or Is It Internet? Experimental Estimates of the Effects of Online Instruction on Student Learning.” Journal of Labor Economics 31 (4): 763–84. https://doi.org/10.1086/669930.

McPherson, Michael S., and Lawrence S. Bacow. 2015. “Online Higher Education: Beyond the Hype Cycle.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 29 (4): 135–54. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.4.135.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2000. “2000 Chinese Census.” http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/Statisticaldata/CensusData/.

Wang, Zhuzhu, Haijun Zeng, and Ying Wang. 2015. “ICT Integration in Rural Classrooms.” In Approach of ICT in Education for Rural Development, edited by Haijun Zeng, Weifeng Xia, Jinghua Wang, and Rong Wang, 67–125. SAGE China Studies.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email