Impacts of Monetary-Fiscal Policy Interaction

China’s 2009 stimulus presents an ideal case for exploring the impacts of monetary-fiscal interaction on credit allocation and investment. During this stimulus period, monetary stimulus itself did not favor SOEs over non-SOEs in credit access. Fiscal expansion, however, enhanced the monetary transmission to bank credit that was allocated to local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) for infrastructure and at the same time weakened the impacts of monetary stimulus on bank credit to non-SOEs in other sectors.

The interaction between monetary and fiscal policies is one of the foremost economic issues facing the world today. Since the seminal work of Leeper (1991), economists and policymakers alike have increasingly recognized the relevance of fiscal policy for central banking. The fiscal relevance to the effectiveness of monetary policy is especially strong when the economy recovers from recessions. After the 2008 global financial crisis, policymakers around the world used both monetary stimulus and massive public spending to boost economic growth. This monetary-fiscal policy interaction has played an even more important role in economic recoveries around the world from the current coronavirus crisis. The 2020 Report of Government Work of China’s State Council called for “pursuing a more proactive and impactful fiscal policy” for financing infrastructure investment, which set the stage for loosening monetary policy through “a variety of tools to enable M2 money supply and aggregate financing to grow at notably higher rates than last year.” The U.S. government has proposed spending a trillion dollars on infrastructure investment as one effective way to stimulate the economy in addition to the Federal Reserve’s monetary stimulus. One important question is how monetary stimulus, by interacting with expansionary public investment, translates into credit allocation to firms and businesses. An answer to this question not only contributes to the macro-finance literature but is also informative for policymakers.

China as a case study

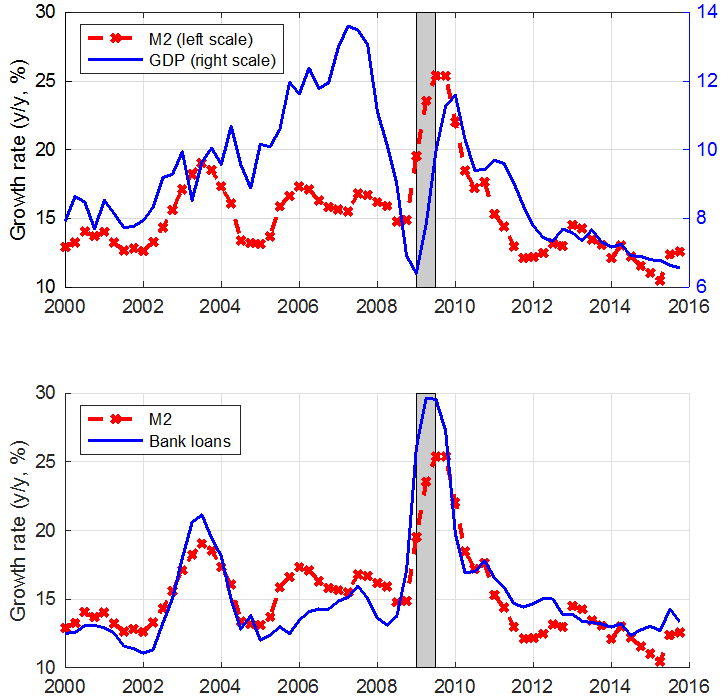

China’s monetary-fiscal policy mix during its 2009 economic stimulus makes it an ideal case study to gain a general perspective on this issue. To stem the sharp fall of aggregate output growth, the People’s Bank of China (PBC) switched to an extremely accommodative monetary policy regime (top chart of Figure 1). The PBC expanded M2 by 4.2 trillion RMB in the first quarter of 2009 and by a total of 11.5 trillion RMB during the first three quarters of 2009. As a result, the growth rate of total bank loans increased by more than 25% during the same period (bottom chart of Figure 1). At the same time, growth in infrastructure investment peaked in 2009Q1-Q2, after the government announced an increase of infrastructure investment as a large part of its stimulus package in November 2008. Local governments’ infrastructure investment has always played a crucial role in China’s economic growth (Xiong, 2019). Under the stimulus plan, new bank credit was disproportionately allocated to state-owned firms rather than to productive private firms (Bai, Hsieh, and Song, 2015; Cong, Gao, Ponticelli, and Yang, 2019; and Huang, Pagano, and Panizza, 2020). What has not been studied is how monetary and fiscal policies interacted with each other to influence credit allocation and business investment.

Figure 1. The time series of annual growth rates of GDP, M2, and bank lending

The shaded bar marks the monetary stimulus period of 2009Q1-Q3. Source: Chen, Gao, Higgins, Waggoner, and Zha (2020).

In a recent paper (Chen, Gao, Higgins, Waggoner, and Zha, 2020), we take a first step in studying how the interaction between monetary and fiscal policies can influence the banking system and the real economy. We use China’s 2009 stimulus as a case study to explore the impacts of monetary-fiscal policy interaction by addressing two questions. First, how did the 2009 monetary stimulus alone translate into credit allocations between different types of firms? Second, how did infrastructure investment affect the monetary transmission? The key finding is that, except for the manufacturing sector, monetary stimulus itself did not favor state-owned enterprises (SOEs) over private firms in credit access. Fiscal expansion, however, enhanced the monetary transmission to bank credit allocated to local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) for infrastructure and at the same time weakened the impacts of monetary stimulus on bank credit to private firms in other sectors. Through this credit channel, monetary stimulus was transmitted into capital investment by crowding in investment by SOEs and crowding out investment by private firms.

Although our analysis in this article is specific to China, its broad policy implications shed light on how monetary and fiscal policies interact in the United States and other economies. One empirical challenge is to isolate monetary stimulus from other policies that drive the fluctuation of infrastructure investment. As argued in the literature, fiscal policy plays an important role in infrastructure investment and large fiscal expansions are often accompanied by a “tsunami of bank credit expansion” (Leeper, Walker, and Yang, 2010; Brunnermeier, Sockin, and Xiong, 2017). If the impacts of monetary stimulus are not separated from those of infrastructure investment driven by fiscal stimulus, estimates of the effects of monetary stimulus and its interaction with infrastructure investment would be biased.

To separate the effects of these two polices, we propose two empirical steps. In the first stage, a structural model is needed to identify exogenous monetary policy shocks. This allows us to decompose changes in infrastructure investment into changes caused by exogenous monetary policy shocks and changes caused by shocks orthogonal to monetary policy shocks, such as fiscal policy shocks. In the second stage, with the series of monetary policy shocks and the series of infrastructure investment driven by non-monetary shocks (both series obtained in the first stage), one can estimate the direct effects of monetary policy as well as its interaction with infrastructure investment on new loan issuance with the micro data.

Quantifying the impacts of monetary-fiscal policy interaction in China

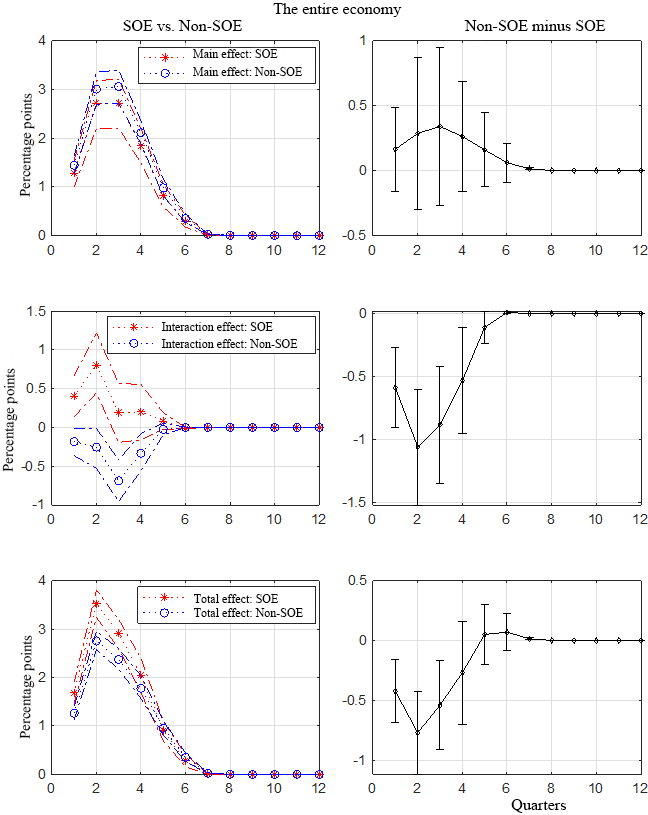

According to Chen, Gao, Higgins, Waggoner, and Zha (2020), the 2009 monetary stimulus alone disproportionately favored credit access by SOEs in the manufacturing sector. At the same time, infrastructure investment driven by non-monetary shocks, such as fiscal policy shocks, weakened the monetary effect on bank credit to private manufacturing firms. In non-manufacturing sectors, firms enjoyed implicit government loan guarantees because a majority of private firms were large and capital intensive (Chang, Chen, Waggoner and Zha, 2015). For the entire economy, therefore, monetary stimulus alone did not favor SOEs over private firms in credit access. In fact, without fiscal stimulus, the cumulative effect of monetary stimulus is larger on loans to private firms than on loans to SOEs (top chart of Figure 2).

Figure 2. Dynamic impacts of the main monetary stimulus (no interaction) and its interaction with infrastructure investment on bank loans to the average SOE firm and the average non-SOE firm

The right column displays the non-SOE loan response relative to the SOE loan response. The dynamic responses are expressed as percentage changes from the initial quarter 0 (i.e., changes from the non-stimulus period). Dash-dotted lines and error bars represent the corresponding .90 probability bands computed from the econometric model. Quarter 1 corresponds to 2009Q1 and quarter 12 corresponds to 2011Q4.

Source: Chen, Gao, Higgins, Waggoner, and Zha (2020).

Fiscal stimulus, however, crowded out bank credit to private firms in sectors other than infrastructure and crowded in loans to SOEs. LGFVs played a crucial role in SOEs. Because bank loans to LGFVs had explicit local government guarantees (especially during the period prior to the enactment of Article No. 43 issued by the State Council in September 2014), the positive effects of monetary-fiscal interaction on bank credit to SOEs were entirely driven by loans to LGFVs. While fiscal stimulus via infrastructure spending amplified the monetary effect on investment by SOEs, it dampened that effect on investment by private firms (middle chart of Figure 2). The total response of SOE investment to the 2009 monetary stimulus was larger than that of private investment (bottom chart of Figure 2). Fiscal stimulus, therefore, was key to understanding the effect of the 2009 monetary stimulus on reallocation of both credit and investment from private firms to SOEs.

Going forward

During the current COVID-19 crisis, there has been a resurgence of using joint monetary-fiscal stimulus to boost economic growth in China, the United States, and other countries. Infrastructure investment has again played a central role in the Chinese government’s stimulus plan. Annual growth of M2 increased from 8.7% at the end of 2019 to 10.9% in September 2020, and annual growth of total social finance (including shadow banking) increased from 10.7% at the end of 2019 to 13.5% in September 2020. At the same time, according to the Ministry of Finance, local government bonds issued in 2020 reached 3.2 trillion RMB by May 2020, with all funds from bond issuance flowing to the infrastructure sector and public services. The growth rate of infrastructure investment was about 8 percent in June, July, and August 2020.

The experience of the 2009 monetary stimulus teaches us that fiscal expansion financed by either bank loans or bond issuances will have similar effects on the transmission of monetary policy. In 2015, the Ministry of Finance issued a notice allowing local governments to issue bonds totaling 14.34 trillion RMB over the next three years to repay maturing bank loans the local governments undertook during the stimulus period. Most of the bonds were purchased by commercial banks, which in turn forced the PBC to inject liquidity into the banking system, via medium-term lending facilities, to finance these bond purchases. With implicit or explicit government guarantees on bank lending in China, fiscal stimulus via public investment may undermine the effectiveness of monetary policy in channeling funds from commercial banks into private firms. The United States and other developed countries have different economies. A vast majority of firms are private firms and there are no implicit or explicit government guarantees on bank loans to private firms. Whether fiscal expansion via public investment will enhance or undermine the transmission of monetary policy into the banking system and business investment remains an important topic to study in the future.

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta or the Federal Reserve System.

(Kaiji Chen, Economics Department, Emory University and Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta; Haoyu Gao, Central University of Finance and Economics; Patrick Higgins, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta; Daniel F. Waggoner, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta; Tao Zha, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and Emory University.)

References

Bai, C.-E., C.-T. Hsieh, and Z. M. Song (2016): “The Long Shadow of a Fiscal Expansion,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, 129–181.

Brunnermeier, M. K., M. Sockin, and W. Xiong (2017): “China’s Gradualistic Economic Approach: Does It Work for Financial Development?,” American Economic Review Papers & Proceedings, 107, 608–613.

Chang, C., K. Chen, D. Waggoner and T. Zha (2016), “Trends and Cycles in China's Macroeconomy,” NBER Macroeconomics Annual, Vol. 30 (lead article), 1–84.

Cong, L. W., H. Gao, J. Ponticelli, and X. Yang (2019): “Credit Allocation Under Economic Stimulus: Evidence from China,” Review of Financial Studies, 32, 3412–3460.

Hsieh, C.-T., and P. J. Klenow (2009): “Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP in China and India,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, CXXIV(4), 1403–1448.

Huang, Y., M. Pagano, and U. Panizza (Forthcoming): “Local Crowding Out in China,” Journal of Finance.

Leeper, E. M. (1991): “Equilibria under ‘Active’ and ‘Passive’ Monetary and Fiscal Policies,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 27, 129–147.

Leeper, E. M., T. B. Walker, and S.-C. S. Yang (2010): “Government Investment and Fiscal Stimulus,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 57, 1000–1012.

Xiong, W. (2019): “The Mandarin Model of Growth,” Unpublished Manuscript, Princeton University.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email