China’s Digital Economy: Opportunities and Risks

China’s digital economy has expanded rapidly in recent years, including both the emergence of new digital industries and the digitalization of traditional sectors. This brings significant opportunities but also potential risks. The blog discusses the pros and cons of digitalization and how the government can do better in maximizing the benefit while minimizing the risks.

Information and communication technologies have grown rapidly over the decades, from microelectronics in the 1940s to the introduction of the internet and smart phones in the 1990s and 2000s. Now, as blockchain, artificial intelligence, and robotics emerge, fast-evolving technologies are creating new sectors, including e-commerce, fintech, big data.

In this new digital economy, China is becoming a global leader in some sectors, particularly e-commerce and fintech. As is seen in other economies, the explosion of new technologies is challenging the boundaries of the digital economy and spurring discussion of its implications.

A narrow definition of the digital economy refers to the information and communications (ICT) sector only, including telecommunications, internet, IT services, hardware and software, and so on. A newer, broader definition includes ICT and those parts of traditional sectors that have been integrated with digital technology. The G20 (see Note 1) uses this broad concept and has defined the digital economy as “a broad range of economic activities that includes using digitized information and knowledge as the key factor of production, and modern information networks as the important activity space.”

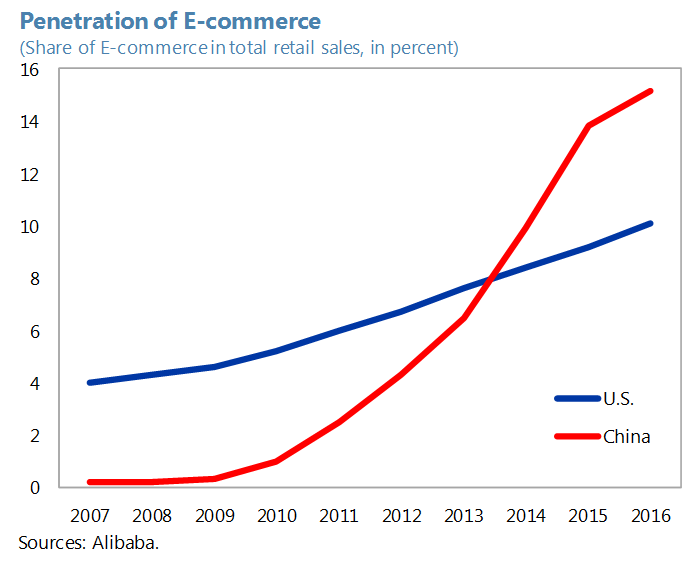

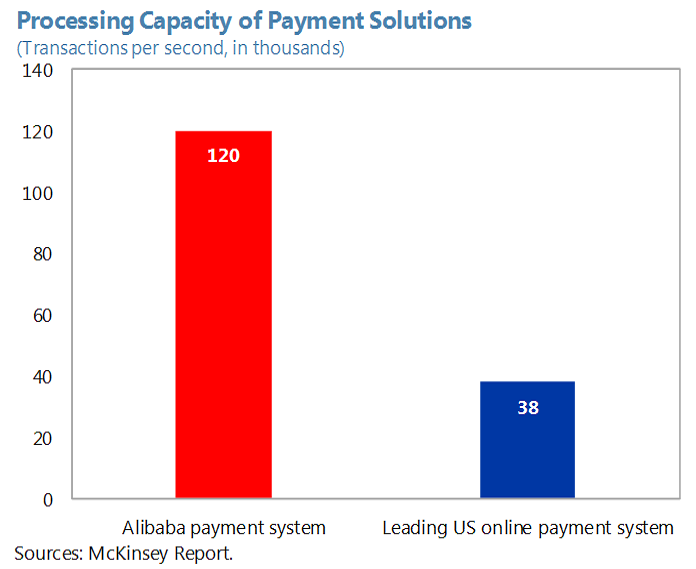

For e-commerce, the latest figures indicate that its penetration in China stands at 15 percent of total retail sales, compared to 10 percent in the United States. Meanwhile, Alibaba’s mobile payment processing capacity is roughly 3 times that of its leading U.S. counterpart.

While China has become a global leader in several new sectors, much scope remains for further digitalization of the overall economy. OECD estimates based on a narrow definition puts China’s digital economy at 6 percent of GDP, compared to 8–10 percent in Japan and Korea, where IT sectors are more developed and dominant. Under the broader definition, China’s digital economy stands at about 30 percent of GDP — based on estimates by the China Academy of Information and Communication Technology — compared to 59 percent in the United States, 46 percent in Japan, and about 20 percent in major emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, and South Africa.

The degree of digitalization also varies across provinces and sectors and is broadly in line with income level, reflecting the diverse stages of economic development across the country. In Beijing and Shanghai, for example, the digital economy is close to 45 percent of GDP, which is similar to Japan; while in central Henan province, the size is only 15 percent of provincial GDP. By sector, overall services are most digitalized, with ICT contributing to 33 percent of value-added in 2017; the industrial (17 percent) and agricultural sectors (7 percent) are lagging. Subsectors also vary substantially. In services, the most ICT-intensive subsectors are mostly in financial services and entertainment; in the industrial sector, advanced manufacturing is more digitalized.

Digitalization has given a major boost to China’s productivity growth. Zhang and Chen (2019) show that a 1 percentage point increase in the economy’s overall digitalization is associated with an increase of a 0.3 percentage point of GDP growth. Digitalization has improved efficiency through several channels. First, lower transaction costs. For example, financial transactions that had required visiting bank branches can now be completed in seconds on mobile phones. Second, reduced information asymmetry and better matching of demand and supply. The ecosystem established by the tech giants in China provides small suppliers with instant access to a large pool of consumers. Big data analytics also reveal consumer preferences and help target service provision. Third, enhanced production efficiency. In the manufacturing sector, automation has led to shorter cycle times and improved quality and reliability.

While digitalization has created new jobs, it has also disrupted employment in some sectors. This is most evident in the industrial sector, while the impact on the service sector has been limited. Industrial employment has fallen by 9 million since 2012 — a result of overcapacity cuts, and, to some extent, automation-driven industrial upgrading. For example, Foxconn, a leading ICT company, replaced 60,000 workers with 40,000 robots.

Meanwhile, the booming e-commerce sector and the sharing economy have driven a new engine of job creation. Alibaba’s platform has almost 11 million SMEs, which have created over 30 million jobs over the past decade. The Didi taxi platform (China’s equivalent of Uber) is connected to 13 million drivers. Overall, the net impact of digitalization on employment is likely positive in China.

Finally, digitalization has promoted economic rebalancing. The rapid penetration of digital apps has supported the development of the service industry as tech giants’ “super apps” provide consumers one-stop shops for all services, ranging from entertainment, dining, education, and health. Digitalization has also promoted green development, making it easier to track and thus reduce carbon emissions. For example, Ant Financial’s Ant Forest, a mobile application, integrates carbon emission tracking with users’ daily consumption activities, linking the gaining of green points to actual tree planting. By the end of 2017, the app had 288 million users, helping to reduce more than 2 million tons of carbon emissions and leading to the planting of more than 13 million trees.

Digitalization is also associated with many new challenges and risks. In the labor market, it could increase labor market polarization, or a “hallowing out” of the medium-skilled, thus boosting the wages and employment of high- and low-skilled labor relative to those in the middle. The rise of fintech, meanwhile, has transformed the provision of financial services and its market structure, but has in turn created regulatory challenges. Issues related to data privacy and cybersecurity have become more prominent in the digital era. The dominance of tech giants in digital sectors raises concerns about the impact of monopoly power on innovation and market stability, creating challenges for policy makers.

The government can play a vital role in maximizing the benefits of digitalization while helping to minimize the related costs and risks. To better prepare the labor market for the digital age, government can promote proactive training of the labor force and strengthen social safety nets. It should also promote healthy competition and data sharing across different digital platforms, strengthening the protection of intellectual property rights and data privacy, and harmonizing regulation by adopting an activity-based regulatory approach on fintech. Given the advances made by many Chinese fintech firms, China could play an important role in international policy forums by helping set standards on governance in cybersecurity and digital transactions and on policies designed to harness digital dividends and help workers manage the economic transition.

Note 1: G20 Digital Economy Development and Cooperation Initiative.

The blog is based on the IMF working paper, “China’s Digital Economy: Opportunities and Risks,” by Longmei Zhang and Sally Chen,

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/01/17/Chinas-Digital-Economy-Opportunities-and-Risks-46459.

(Longmei Zhang, an economist in Asia and Pacific Department, International Monetary Fund; Sally Chen, IMF’s Resident Representative for Hong Kong SAR.)

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email