Can Information Influence the Social Insurance Participation of China’s Rural Migrants?

We use a randomized information intervention to shed light on whether poor understanding of social insurance—in terms of both the enrollment process and the associated costs and benefits—drives the relatively low rates of participation in urban health insurance and pension programs among China's rural-urban migrants. Among workers without a contract, the information intervention has a strong positive effect on participation in health insurance and, among younger age groups, in pension programs. Migrants are responsive to price: in cities where the premiums are low relative to earnings, information induces health insurance participation, while declines are observed in cities with high relative premiums.

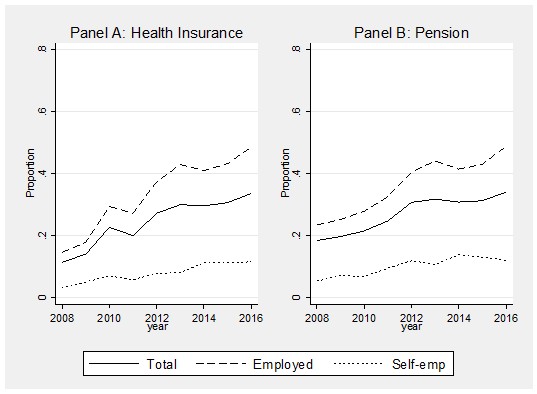

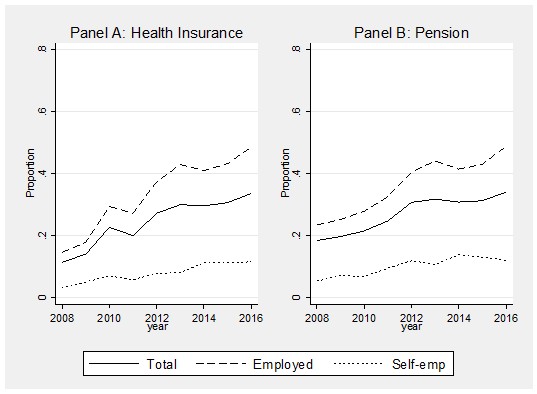

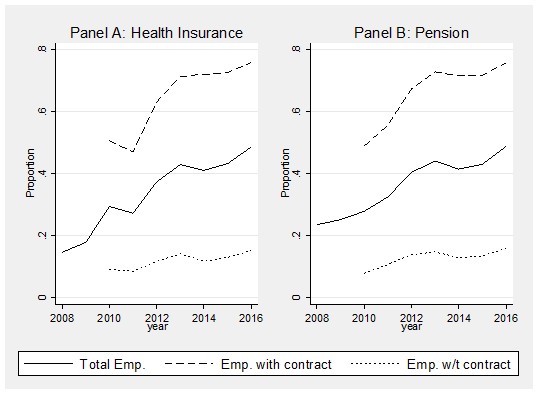

Over the past three decades, with the growth of China’s economy, hundreds of millions of rural workers moved to cities for work. By 2017, there were 172 million rural migrant workers in Chinese cities (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2017). Despite their considerable contributions to China’s economic growth, the rural-urban migrants are not treated equally to their urban counterparts. In particular, the majority of rural workers are not covered under the city social welfare system. While the central government has passed laws promoting increases in the social insurance participation rates of migrant workers, such as the Labour Control Law in 2008 and the Social Insurance Law in 2011, participation rates of migrants in the urban program remains very low (see Figure 1).

Note: The solid line denotes the full migrant sample. The dash line denotes the employed (wage-salary earners) sample, and the dotted line denotes the self-employed sample.

Source: RUMiC Survey 2008-2016

There are several reasons for low participation rates. First, although the central government has passed laws and regulations to increase migrant participation rates, implementation details and enforcement of these laws and regulations are left to local governments. As local leaders are generally evaluated on how well they meet growth targets, the prospect of rising labor costs is a frequent concern for them and reduces their incentives to enforce laws requiring employers to make payroll contributions to social insurance funds. Furthermore, unless they are particularly law-abiding, employers also have no incentive to make voluntary contributions when enforcement is not effective. Second, the financing of social insurance schemes is also left to local governments, but decentralized administration continues to limit the portability of social insurance accounts, and thus limits the willingness of migrants to participate. While payments made by firms and by young, healthy migrants are positive contributions to local health insurance and pension funds, most local governments are reluctant to transfer funds to other regions when migrants relocate, as this would have immediate budgetary consequences. Third, existing rural programs may be viewed as substitutes for “expensive” urban insurance schemes, even though rural programs provide much lower benefits relative to urban programs. Finally, rural migrants may lack the information and knowledge of urban social insurance programs and therefore not seek to participate. No one really knows the relative importance of these various factors to low participation.

We conducted a field experiment to examine this last potential reason: the role of information on migrants’ participation in urban social pension and health insurance programs, based on the Rural-Urban Migration in China (RUMiC) survey. The RUMiC survey follows 5,000 migrant households in 15 cities over the period of 2008-2016. The experiment was conducted over the period of 2015 and 2016 waves. It consists of three stages: the baseline wave (i.e., the 2015 wave of the RUMiC survey), the intervention, and the follow-up wave (i.e., the 2016 wave). During the intervention stage, around one third of the migrant households of the baseline wave were randomly selected to receive pamphlets which provide simplified and easy-to-follow information on the city-specific costs, benefits, and portability of the social pension and health insurance programs. We evaluated the effect of the information intervention by comparing the treatment group who received the pamphlets with the control group who did not receive the pamphlets.

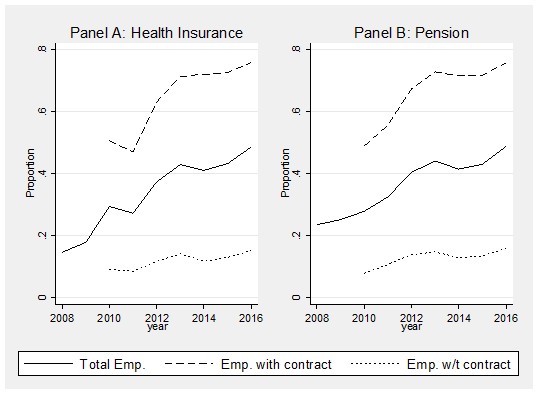

Over the full sample, the average information intervention effect is not statistically significantly different from zero, which suggests that, across-the-board, lack of information may not be an important factor for low participation rate. However, this “zero average effect” masks considerable and interesting heterogeneity across workers in the formal and informal sectors and across cities. For individuals with an employment contract (i.e., formal sector employment), program participation rates were already quite high at 76% for health insurance and 74% for pension programs in 2015 (see Figure 2). In our sample, however, over 68% of migrants were employed in the informal sector (without employment contracts). Perhaps responses to the information differed by groups.

Heterogeneity of Treatment with Workers in Formal and Informal Sectors

For the subgroup of migrants employed in the formal sector (with a contract), the intervention had little effect on either pension or health insurance participation. For the workers in the informal sector, however, the information intervention led to a 3.2 percentage point increase in enrollment in health insurance, which is a 23% increase from the baseline 13.8% enrollment rate. The effect of the intervention on pension program participation was also positive and significant for those informal sector workers who were young enough to contribute for the fifteen-year minimum necessary to reap full benefits from the program. We find a 3.9 percentage point increase for young informal employees, which is an economically significant 26% increase from their baseline 15% enrollment rate. These are very large increases in response to a very simple intervention.

More interestingly, for those older workers who could not work long enough to reap full pension benefits, we observed a 7.2% increase in wages (no similar increase is observed from the “young” workers) by comparing the treatment and control groups, which is roughly half the minimum required employer contribution to individual pension accounts. As this occurs with no participation effect for older workers, it provides some evidence of collusion between employers and employees. Older informal sector workers, who could not benefit as much from participation, effectively bargained with employers over wages, and employers benefited by avoiding the full cost of paying into the mandated urban employee pension program for older employees.

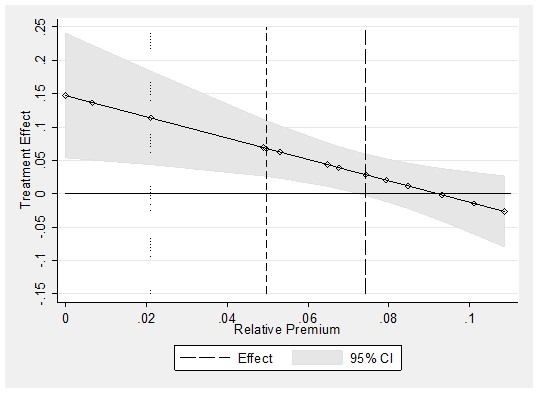

Heterogeneity of Treatment with the Relative Premium

Apart from possessing a contract, differences in relative premium levels across cities may also introduce heterogeneity in the treatment effect. Among the 15 cities in the RUMiC survey, there were large variations in the relative premium (defined as the premium over city-level average migrant wages). For example, in the case of health insurance premiums, some cities’ employee contributions only account for less than 1% of the city average wages, while in other cities the required contributions account for more than 11%. The variation across cities for the pension scheme is between 9% and 22% of the city-level average wages.

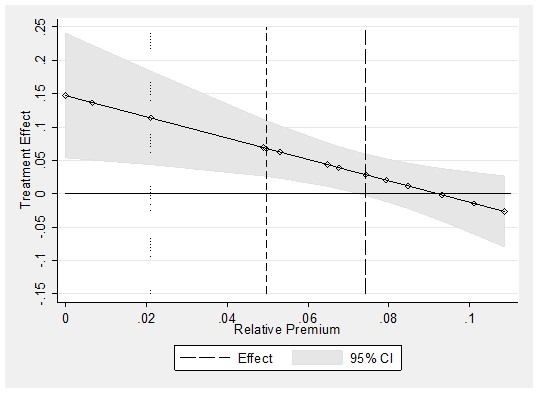

We find that the required individual contribution affects the take-up rate: the larger the contribution, the less the information intervention affects take-up. On average the price elasticity of the health premium on the treated group is a negative 1.18, indicating that a 1% increase in the relative health insurance premium reduces participation by 1.18 percentage points. Further investigation into formal and informal sectors reveals that the informal sector migrants in cities with low relative premiums were even more responsive to the information intervention. We observe 6.7 and 11.2 percentage point increases in health insurance participation among migrants in cities at the 25th and 10th percentiles of the relative premium distribution, respectively (see Figure 3).

In contrast with the decision to participate in health insurance, pension program participation is not sensitive to the city-wide relative premium. One explanation for the difference in responsiveness may derive from the fact that the health insurance available from rural counties (through the New Rural Cooperative Medical System policy) is a closer substitute for urban employee health insurance than the subsidized new rural pension is for urban employee pensions. Another possible explanation is that participation in the pension scheme requires people to plan over a longer time horizon.

Conclusions

In both China and the international policy communities, there is a broad recognition that social insurance has an important role to play in the process of economic development and urbanization. However, there is a tendency for those providing policy advice to simply assume that “mandating participation” in a social insurance scheme will be sufficient to cover informal sector workers. The experience of China should offer caution to the belief that mandates alone will suffice to raise participation. Informal sector workers are often not participating in urban employee social insurance schemes for a number of reasons. Finding a way to bring informal sector workers into social insurance systems may pose a challenge for policy makers in many settings. Results from our research suggest that lack of information may contribute to reducing participation among informal sector workers, and that providing information may be a relatively low cost means of raising coverage.

Information interventions alone, however, are unlikely to bring full urban health insurance coverage to the rural migrant population. A one year boost in coverage of 3.2 percentage points still leaves more than 80 percent of migrants without employment contracts lacking health insurance coverage in the cities where they work. While further research may demonstrate the potential for information interventions to have a cumulative effect over time and to be reinforced by steps to reduce the transaction costs associated with enrolling, it is likely that greater institutional reforms will be necessary for achieving full coverage. In particular, there may be a need to unify health insurance programs across urban and rural areas, in order to increase the portability of schemes, and to provide premium subsidies for lower income workers.

References

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2017). 2017年农民工监测调查报告. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201804/t20180427_1596389.html

Over the past three decades, with the growth of China’s economy, hundreds of millions of rural workers moved to cities for work. By 2017, there were 172 million rural migrant workers in Chinese cities (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2017). Despite their considerable contributions to China’s economic growth, the rural-urban migrants are not treated equally to their urban counterparts. In particular, the majority of rural workers are not covered under the city social welfare system. While the central government has passed laws promoting increases in the social insurance participation rates of migrant workers, such as the Labour Control Law in 2008 and the Social Insurance Law in 2011, participation rates of migrants in the urban program remains very low (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pension and Health Insurance Program Participation Rates for Migrant Workers

Note: The solid line denotes the full migrant sample. The dash line denotes the employed (wage-salary earners) sample, and the dotted line denotes the self-employed sample.

Source: RUMiC Survey 2008-2016

There are several reasons for low participation rates. First, although the central government has passed laws and regulations to increase migrant participation rates, implementation details and enforcement of these laws and regulations are left to local governments. As local leaders are generally evaluated on how well they meet growth targets, the prospect of rising labor costs is a frequent concern for them and reduces their incentives to enforce laws requiring employers to make payroll contributions to social insurance funds. Furthermore, unless they are particularly law-abiding, employers also have no incentive to make voluntary contributions when enforcement is not effective. Second, the financing of social insurance schemes is also left to local governments, but decentralized administration continues to limit the portability of social insurance accounts, and thus limits the willingness of migrants to participate. While payments made by firms and by young, healthy migrants are positive contributions to local health insurance and pension funds, most local governments are reluctant to transfer funds to other regions when migrants relocate, as this would have immediate budgetary consequences. Third, existing rural programs may be viewed as substitutes for “expensive” urban insurance schemes, even though rural programs provide much lower benefits relative to urban programs. Finally, rural migrants may lack the information and knowledge of urban social insurance programs and therefore not seek to participate. No one really knows the relative importance of these various factors to low participation.

We conducted a field experiment to examine this last potential reason: the role of information on migrants’ participation in urban social pension and health insurance programs, based on the Rural-Urban Migration in China (RUMiC) survey. The RUMiC survey follows 5,000 migrant households in 15 cities over the period of 2008-2016. The experiment was conducted over the period of 2015 and 2016 waves. It consists of three stages: the baseline wave (i.e., the 2015 wave of the RUMiC survey), the intervention, and the follow-up wave (i.e., the 2016 wave). During the intervention stage, around one third of the migrant households of the baseline wave were randomly selected to receive pamphlets which provide simplified and easy-to-follow information on the city-specific costs, benefits, and portability of the social pension and health insurance programs. We evaluated the effect of the information intervention by comparing the treatment group who received the pamphlets with the control group who did not receive the pamphlets.

Over the full sample, the average information intervention effect is not statistically significantly different from zero, which suggests that, across-the-board, lack of information may not be an important factor for low participation rate. However, this “zero average effect” masks considerable and interesting heterogeneity across workers in the formal and informal sectors and across cities. For individuals with an employment contract (i.e., formal sector employment), program participation rates were already quite high at 76% for health insurance and 74% for pension programs in 2015 (see Figure 2). In our sample, however, over 68% of migrants were employed in the informal sector (without employment contracts). Perhaps responses to the information differed by groups.

Figure 2: Participation Rates among Formal and Informal Employees

For the subgroup of migrants employed in the formal sector (with a contract), the intervention had little effect on either pension or health insurance participation. For the workers in the informal sector, however, the information intervention led to a 3.2 percentage point increase in enrollment in health insurance, which is a 23% increase from the baseline 13.8% enrollment rate. The effect of the intervention on pension program participation was also positive and significant for those informal sector workers who were young enough to contribute for the fifteen-year minimum necessary to reap full benefits from the program. We find a 3.9 percentage point increase for young informal employees, which is an economically significant 26% increase from their baseline 15% enrollment rate. These are very large increases in response to a very simple intervention.

More interestingly, for those older workers who could not work long enough to reap full pension benefits, we observed a 7.2% increase in wages (no similar increase is observed from the “young” workers) by comparing the treatment and control groups, which is roughly half the minimum required employer contribution to individual pension accounts. As this occurs with no participation effect for older workers, it provides some evidence of collusion between employers and employees. Older informal sector workers, who could not benefit as much from participation, effectively bargained with employers over wages, and employers benefited by avoiding the full cost of paying into the mandated urban employee pension program for older employees.

Heterogeneity of Treatment with the Relative Premium

Apart from possessing a contract, differences in relative premium levels across cities may also introduce heterogeneity in the treatment effect. Among the 15 cities in the RUMiC survey, there were large variations in the relative premium (defined as the premium over city-level average migrant wages). For example, in the case of health insurance premiums, some cities’ employee contributions only account for less than 1% of the city average wages, while in other cities the required contributions account for more than 11%. The variation across cities for the pension scheme is between 9% and 22% of the city-level average wages.

We find that the required individual contribution affects the take-up rate: the larger the contribution, the less the information intervention affects take-up. On average the price elasticity of the health premium on the treated group is a negative 1.18, indicating that a 1% increase in the relative health insurance premium reduces participation by 1.18 percentage points. Further investigation into formal and informal sectors reveals that the informal sector migrants in cities with low relative premiums were even more responsive to the information intervention. We observe 6.7 and 11.2 percentage point increases in health insurance participation among migrants in cities at the 25th and 10th percentiles of the relative premium distribution, respectively (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: The Treatment Effects on Informal Sector Workers across Cities with Different Relative Health Insurance Premiums

In contrast with the decision to participate in health insurance, pension program participation is not sensitive to the city-wide relative premium. One explanation for the difference in responsiveness may derive from the fact that the health insurance available from rural counties (through the New Rural Cooperative Medical System policy) is a closer substitute for urban employee health insurance than the subsidized new rural pension is for urban employee pensions. Another possible explanation is that participation in the pension scheme requires people to plan over a longer time horizon.

Conclusions

In both China and the international policy communities, there is a broad recognition that social insurance has an important role to play in the process of economic development and urbanization. However, there is a tendency for those providing policy advice to simply assume that “mandating participation” in a social insurance scheme will be sufficient to cover informal sector workers. The experience of China should offer caution to the belief that mandates alone will suffice to raise participation. Informal sector workers are often not participating in urban employee social insurance schemes for a number of reasons. Finding a way to bring informal sector workers into social insurance systems may pose a challenge for policy makers in many settings. Results from our research suggest that lack of information may contribute to reducing participation among informal sector workers, and that providing information may be a relatively low cost means of raising coverage.

Information interventions alone, however, are unlikely to bring full urban health insurance coverage to the rural migrant population. A one year boost in coverage of 3.2 percentage points still leaves more than 80 percent of migrants without employment contracts lacking health insurance coverage in the cities where they work. While further research may demonstrate the potential for information interventions to have a cumulative effect over time and to be reinforced by steps to reduce the transaction costs associated with enrolling, it is likely that greater institutional reforms will be necessary for achieving full coverage. In particular, there may be a need to unify health insurance programs across urban and rural areas, in order to increase the portability of schemes, and to provide premium subsidies for lower income workers.

(John Giles, World Bank; Xin Meng, Australian National University; Guochang Zhao, Southwestern University of Finance and Economics, China; Sen Xue, Jinan University.)

References

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2017). 2017年农民工监测调查报告. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201804/t20180427_1596389.html

Giles, John, Xin Meng, Sen Xue and Guochang Zhao (2018). “Can information influence the social insurance participation decision of China’s rural migrants?” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, WPS8658. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/581891543521508488/Can-Information-Influence-the-Social-Insurance-Participation-Decision-of-Chinas-Rural-Migrants

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email