Misallocation of Managerial Talent in China’s Housing Boom

The housing boom in China has raised great concerns about capital and credit misallocation. Recent research by IMF Economist Yu Shi finds that China’s imperfect financial market and regulations in the land market have also led to a misallocation of managerial talent, dampening productivity and growth in the non-real estate sectors. Productive managers in other sectors moved to the real estate sector, leaving behind the unproductive managers who were unable to accumulate enough wealth to overcome the entry barrier in the land market. Research shows that without this misallocation, the total factor productivity growth in the manufacturing sector would have improved by 0.5% per year.

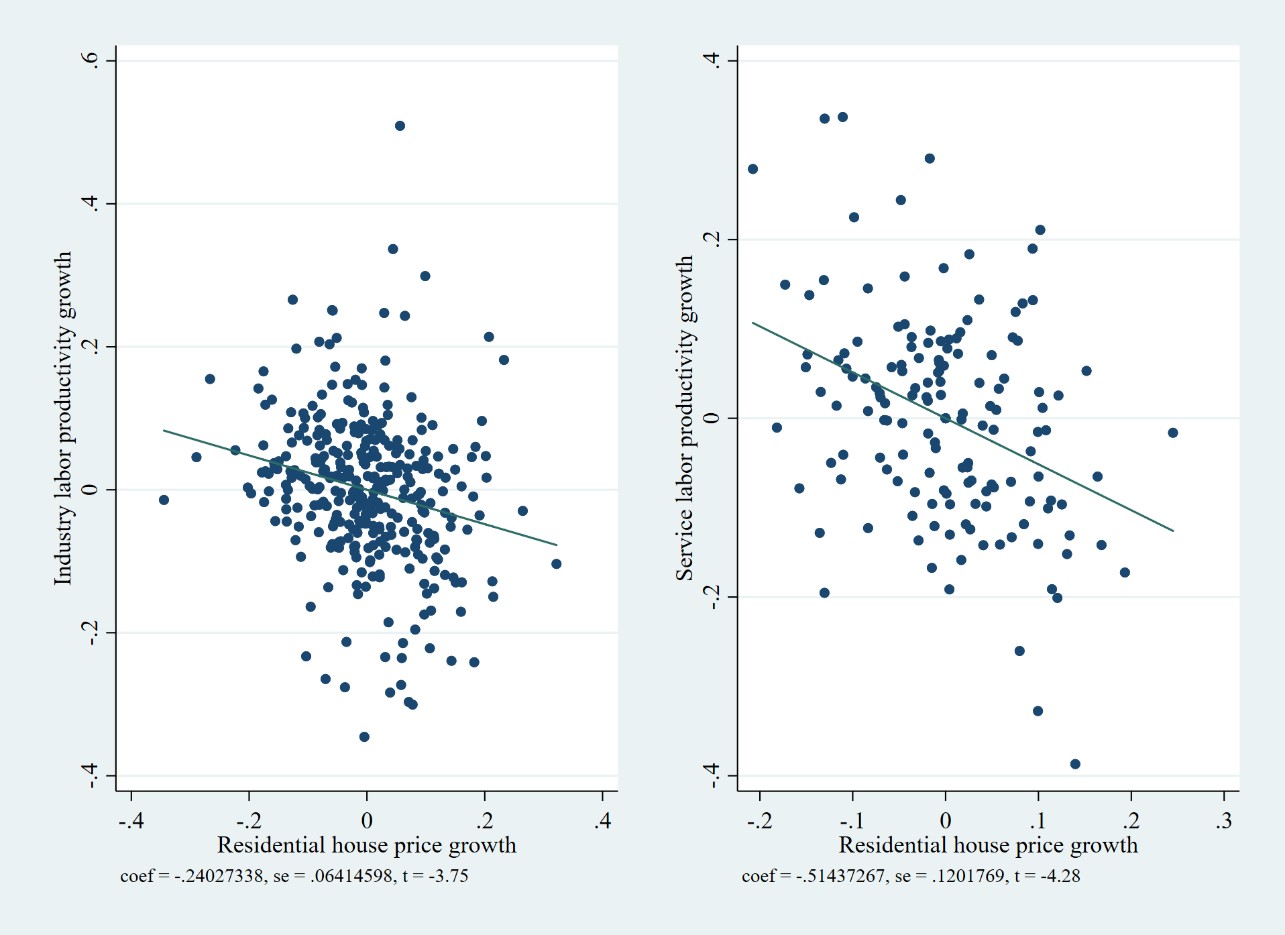

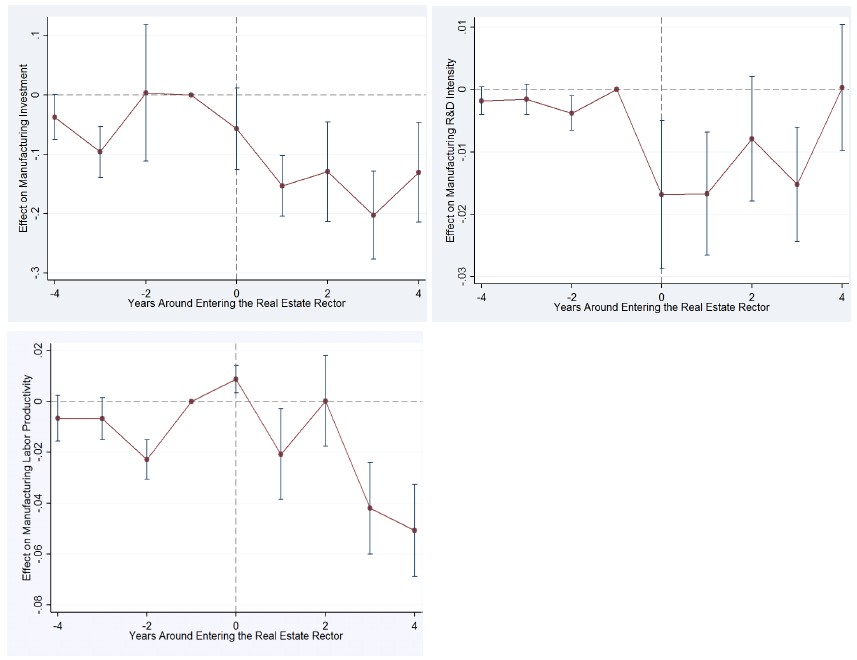

House prices have become an increasingly important indicator for monitoring systemic risks and the need for macro-prudential policy measures (Claessens, 2014). While policymakers are concerned about things like the effect of high house prices on affordability or the ramifications of a burst housing bubble for household and corporate balance sheets (Mian and Sufi, 2011; Mian, Sufi, and Rao, 2013), there could also exist the very real concern of labor and capital misallocations during the run-up of house prices. The literature has looked into possible misallocations in housing booms (Charles, Hurst, and Notowidigdo, 2018; Chen and Wen, 2017; Chen et al., 2017), but it has found them to have limited discussions on productivity. Using prefecture-level official statistics, I find that cities that have experienced higher growth in residential house prices also tend to have more stagnated productivity growth in the (non-booming) non-real estate sector (Figure 1). This evidence suggests that a real estate boom could distort productivity growth in the non-booming sectors and create a “Dutch disease”-like effect.

Note: Figure 1 shows the partial regression plots of industry and service sector labor productivity over local house price growth, controlling for city and year fixed effects. Each dot indicates a city-year observation. The sample covers all Chinese prefectures from 2002 to 2015 depending on data availability. Labor productivity is measured as output over employment at the sector level; house prices are price per square meters of floor area provided by the China Real Estate Index System. Source: City yearbooks and China Real Estate Index System

What would give rise to this effect? Misallocation of managerial talent could be one explanation. Managerial talent misallocation, in this case, meant that following the Chinese real estate boom, there were managers who moved (or reallocated their capital) to the booming real estate sector but who did not have a comparative advantage in managing real estate businesses. In an economy without barriers to entry, managers would choose projects that generate maximum returns to capital. In equilibrium, the firm decision of reallocating capital to the real estate sector would depend solely on managers’ comparative advantage. However, with financial frictions and barriers to entry into the real estate sector, managers in less wealthy firms would be constrained by the entry barrier and thus forced to stay in their original sector. A misallocation of managerial talent would occur, as long as these constrained managers do not have the comparative advantage in the original non-real estate sector.

To establish the misallocation of managerial talent, I start by looking at the patterns of capital reallocation to the real estate sector among private firms. State-owned enterprises are considered less financially constrained in China (Song, Storesletten, and Zilibotti, 2011), and they do not have a strong presence in the land market. I then formally assess the misallocation with a theoretical model and a structural estimation. I calibrate a dynamic model to quantify the aggregate loss of manufacturing total factor productivity (TFP) due to the real estate boom and, finally, analyze policy tools.

Reallocation to the Real Estate Sector

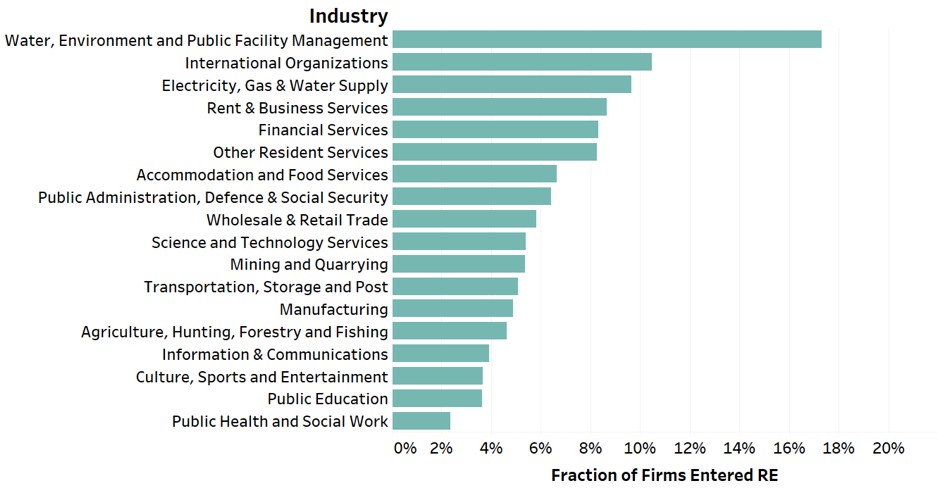

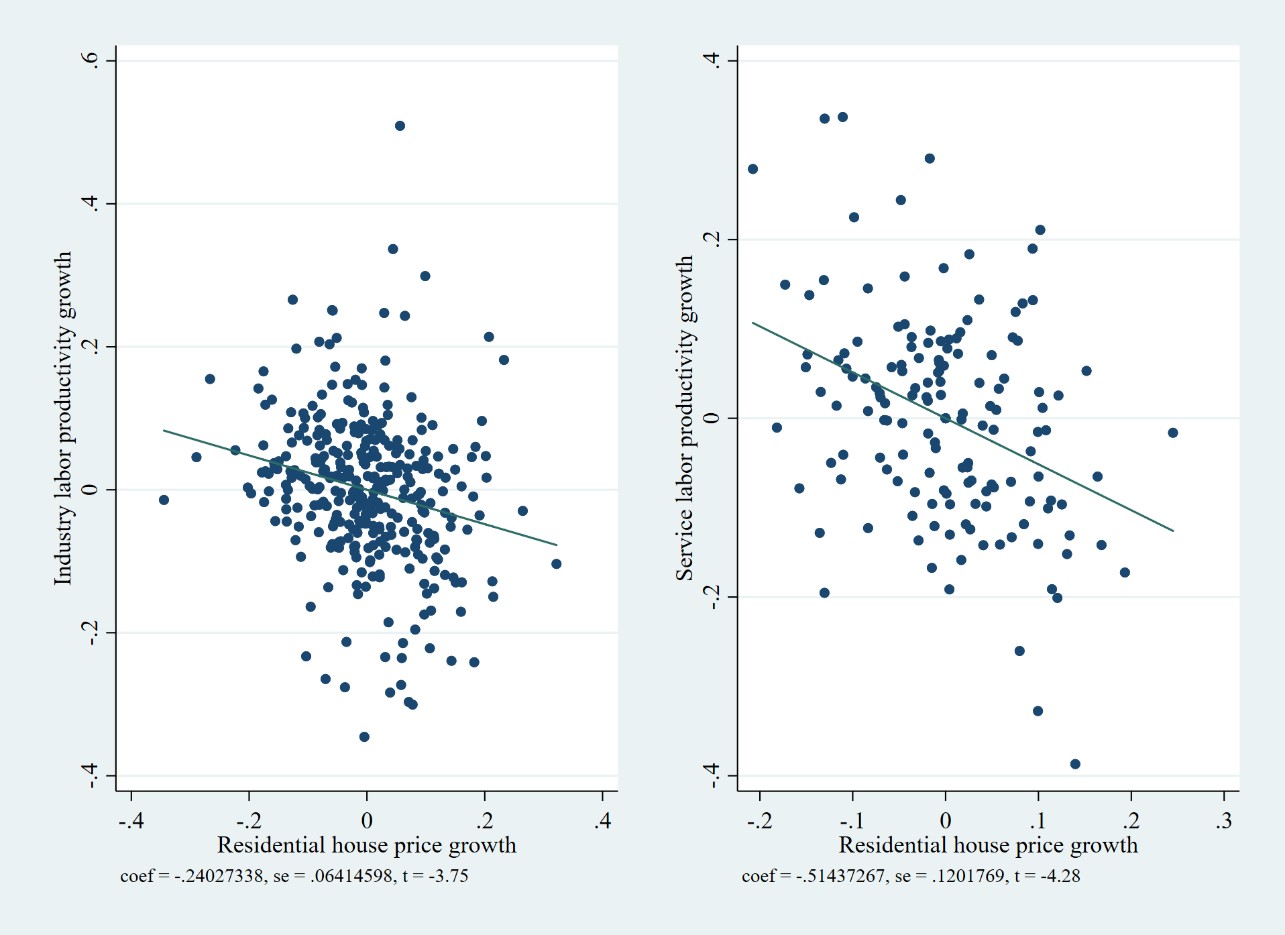

Since the early 2000s, Chinese residential house prices have persistently increased at an annual rate of more than 10% (Fang et al., 2016; Wu, Gyourko, and Deng, 2016). I find from the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC) Firm Registration Data that a sizable number of existing private firms started operating in the real estate sector during the boom. They were involved in real estate development through either the creation of new firms or the acquisition of an existing real estate firm. Figure 2 shows the fraction of firms that had entered the real estate sector by 2010 in 18 non-real estate sectors. More than 8% of firms in sectors including utilities, financial and business services, environmental services have invested heavily in real estate.

Source: The Firm Registration Data of State Administration for Industry and

Commerce and author’s calculations

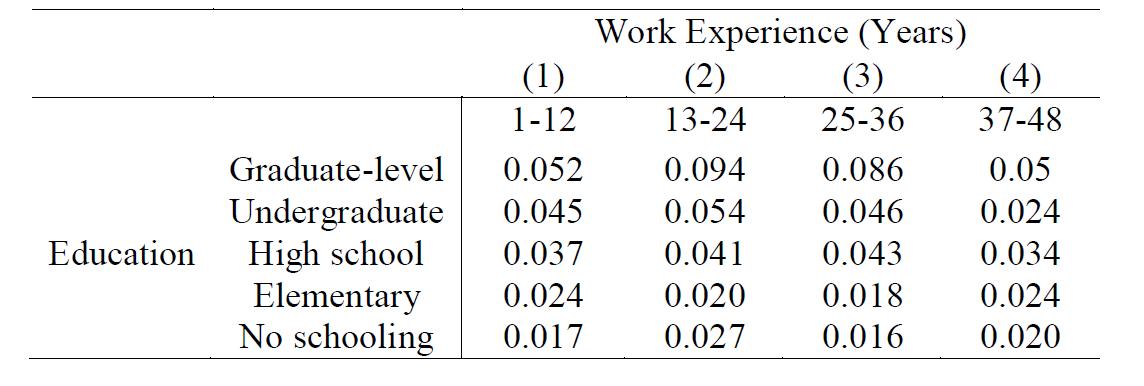

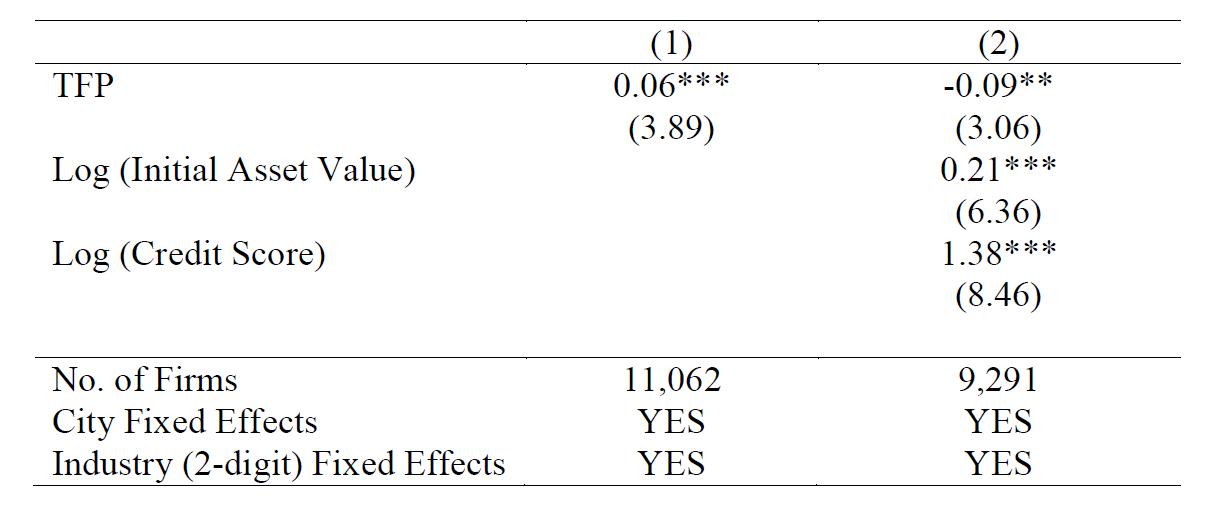

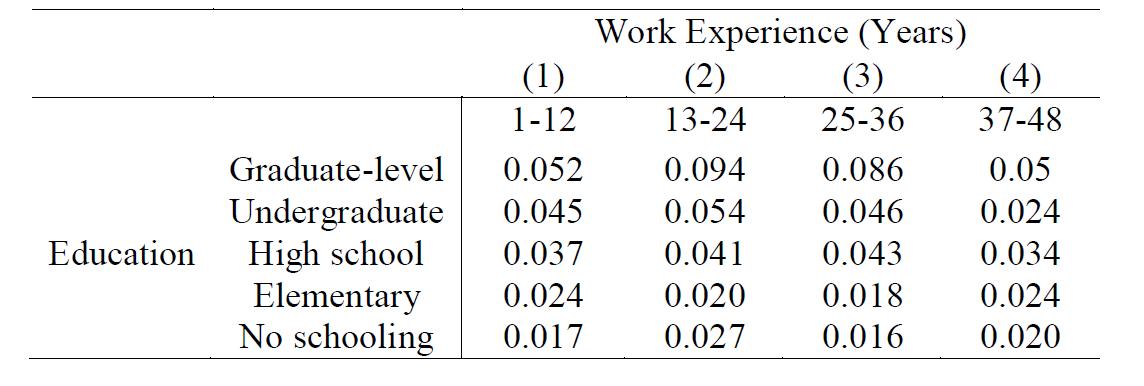

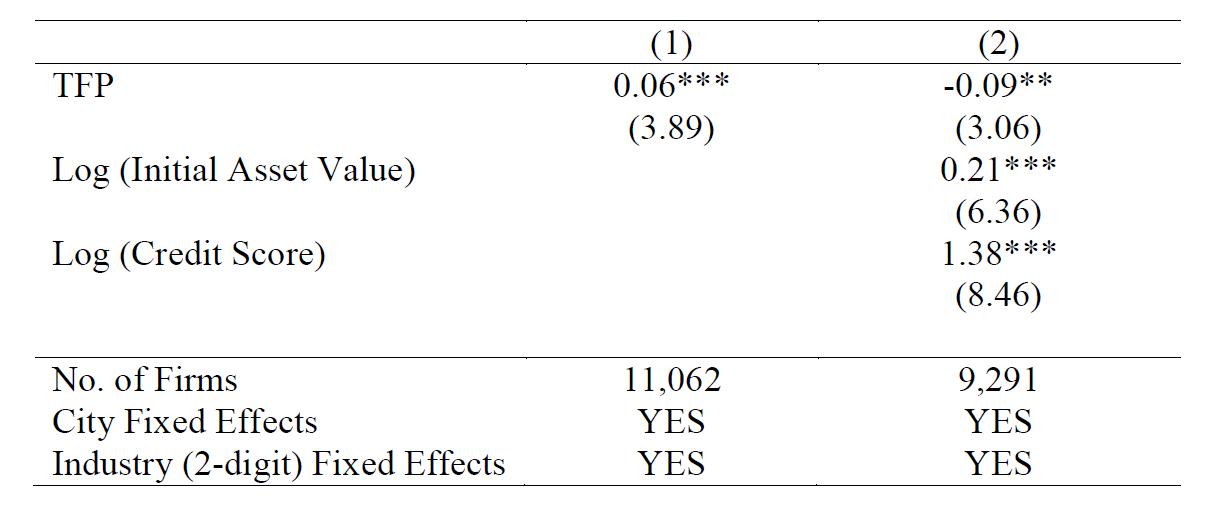

The selection of private firms into the real estate sector is not random. On average, firms that began real estate businesses are larger with higher profit margins, higher credit scores, and tend to invest more in fixed assets and R&D activities. More importantly, these firms are also more productive within their original sector. Table 1 shows that a larger fraction of managers among the group that has more experience and higher levels of education entered the real estate sector during the boom. There is also a positive correlation between pre-boom TFP and the likelihood of entering the real estate sector (column (1) of Table 2), indicating that firms that produce more efficiently tend to move away from their original businesses and into the real estate business. One possible explanation is that better-performing firms could face less binding financial constraints. Controlling for firm-specific pre-boom asset value and credit score, I show in column (2) of Table 2 that the pattern in column (1) is reversed: firms with inferior performance or more inexperienced managers are more likely to start up real estate businesses in the boom given similar financing abilities.

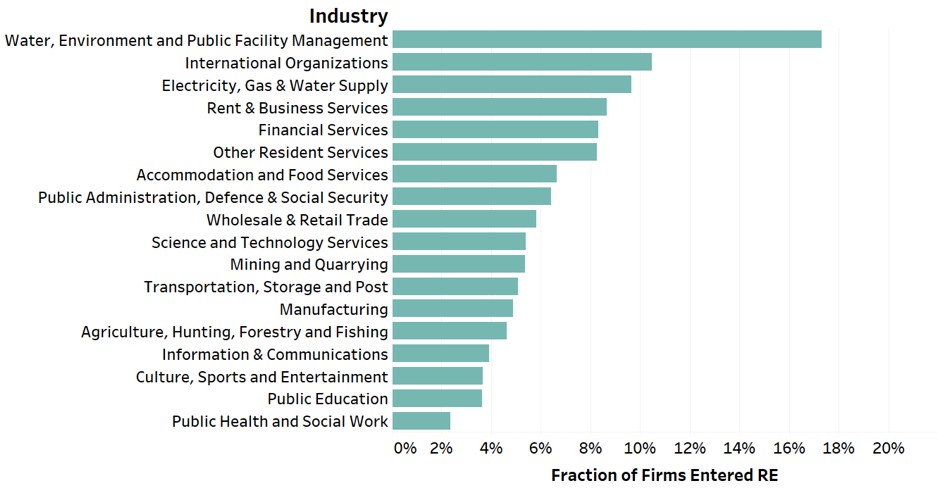

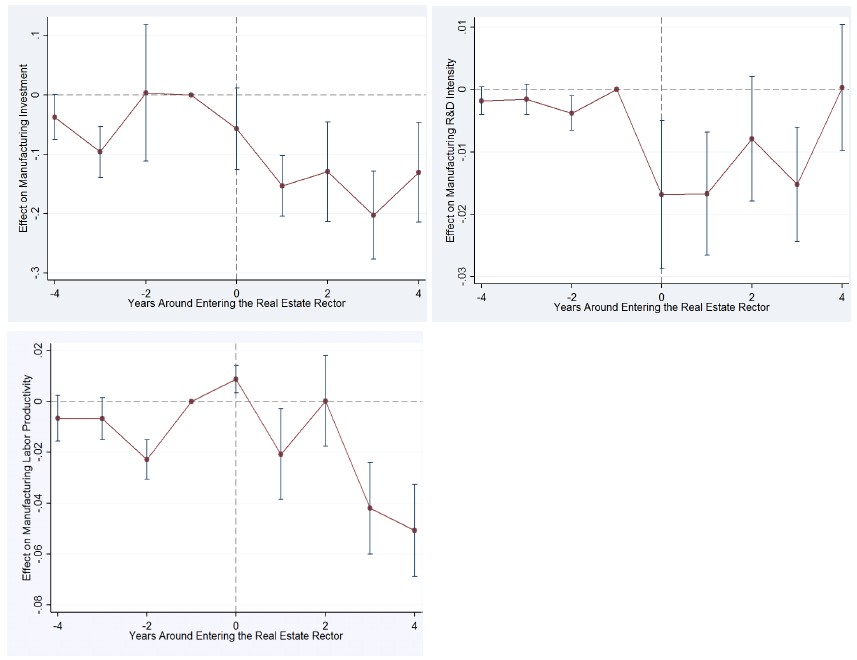

Within private firms, the boom also led to a reallocation of capital to the real estate sector instead of a simple business expansion. Manufacturing sector investment, R&D, and labor productivity declined significantly following a firm’s entry into the real estate sector. Thus, the entries observed in Figure 2 changed the allocation of managerial talent across sectors. Admittedly, a key challenge to this argument is the possibility that declining manufacturing opportunities are what drove the real estate sector entries and explain the declining investment in the manufacturing businesses. I provide causal evidence of within-firm capital reallocation using an instrumental variables approach which exploits factors that are only crucial to real estate businesses: specifically, how managers’ possible connections with the local land bureau (based on their ethnic enclaves) interacted with local land supply constraints (following Saiz, 2010). The instrument is valid as long as manufacturing firms with better access to land are not relatively more advantageous in the manufacturing sector when land supply is adequate. Figure 3 provides the event study analyses on entering the real estate sector. The decline in labor productivity does not happen immediately after entering the real estate sector. This is likely due to the internal capital market selection, which eliminates the relatively unproductive projects within the manufacturing sector causing labor productivity to go up temporarily.

The empirical evidence characterizes the capital reallocation decisions of private business owners and highlights the importance of financial market imperfections. Being financially constrained, a private manager would face the trade-off between real estate and manufacturing investment opportunities. Since the real estate sector is more profitable but also has a substantial entry barrier, each manager’s financing ability becomes a key determinant for starting up real estate businesses. Upon the decision to enter the real estate sector, costly land acquisitions might result in declines in investment, R&D expenditures, and productivity in firms’ manufacturing businesses.

Misallocation and Social Inefficiency

To formally establish the misallocation of managerial talent, I develop a theoretical model and structurally estimate the comparative advantage of private firm managers. The model captures the private firms’ problem: each firm’s maximum borrowing capacity increases with its net worth, and managers have heterogeneous talents in both the manufacturing sector and the real estate sector. The real estate boom in China is assumed to follow privatization in the real estate sector. After the privatization, each firm produces in the manufacturing sector and the real estate sector to maximize its profit, but the real estate sector has an entry barrier that varies with land price. In this model, a firm’s borrowing constraint implies that firm wealth was proportional to managers’ manufacturing talent before the real estate boom. When these managers’ comparative advantages lie in the manufacturing sector, a misallocation of talent occurs because the ones with a comparative advantage in the real estate sector were forced to stay outside due to a lack of wealth. In addition, given that the actual size of the entry barrier varies with land prices, there is a pecuniary externality, which leads the competitive equilibrium to deviate from the second-best scenario.

To estimate the comparative advantage of private firm managers, I revisit the firms that started conducting real estate businesses during the boom and compare their performance in both the manufacturing sector and the real estate sector. Firms with a higher average return to capital in the manufacturing sector do not generate even higher returns in the real estate sector. This evidence suggests that the wealthy and also better-performing manufacturing firms do not have a comparative advantage in the real estate sector, so they should not have moved.

The Aggregate Effect on Manufacturing Productivity Growth

To estimate the aggregate effect of the real estate boom on the productivity growth of the manufacturing sector, I generalize the theoretical model to the infinite horizon. This quantitative exercise extends the model in Song et al. (2011) by including multiple groups of entrepreneurs with heterogeneous talent and multiple sectors. My estimation shows that the real estate boom led to at least a 0.5% decline in manufacturing TFP growth, and a lower land price at the beginning of the boom due to the lack of competition in the land market.

Finally, based on the quantitative framework, I analyze three policy tools that are potentially welfare-improving: liberalizing the financial market, reducing the entry barrier in the real estate sector, and taxing the returns from operating in the real estate sector. Liberalizing the financial market, equivalent to relaxing firm borrowing constraints, improves social welfare but also aggravates social inefficiency. With more effective financial intermediaries, the already wealthy firms can borrow more, which further increases land prices. As a result, more firms with low wealth and the comparative advantage in the real estate sector are constrained by the entry barrier. Lowering the entry barrier in the real estate sector has an ambiguous impact on welfare. It creates more investment opportunities, so generally, untalented managers continue to run their businesses, resulting in a decline in total credit supply. Taxation on real estate returns can improve both social welfare and efficiency. The gains are economically significant: a 3% tax on real estate returns improves post-boom manufacturing productivity growth by 0.3% on average.

Conclusion

I show new empirical evidence that during the Chinese real estate boom, more productive manufacturing firms diverted their resources to the real estate sector, resulting in a decline in R&D, investment, and productivity growth in their manufacturing businesses. This implies a misallocation of managerial talent since the more productive managers do not have the comparative advantage in the real estate sector. A new insight emerging from this discussion is that productivity loss may exist even in the absence of a housing bubble, which differs from related works (Charles, Hurst, and Notowidigdo, 2018; Chen and Wen, 2017; Mian, Sufi, and Rao, 2013). The model can also be used to study other booming sectors, as long as they also require both a costly barrier to entry and that existing business owners reallocate from other sectors to the booming sectors. For instance, the talent misallocation channel can help examine the natural resource booms (the “Dutch disease”) observed when countries with abundant natural resources experience a significant productivity slowdown following a positive shock to commodity prices.

Charles, Kerwin Kofi, Erik Hurst, and Matthew J. Notowidigdo (2018). “Housing booms and busts, labor market opportunities, and college attendance.” American Economic Review 108.10: 2947-94.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20151604

Chen, Kaiji, and Yi Wen (2017). “The great housing boom of China.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 9.2: 73-114.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/mac.20140234

Chen, Ting, et al. (2017). “Real Estate Boom and Misallocation of Capital in China.” Unpublished Manuscript, Princeton University.

https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=CICF2018&paper_id=915

Claessens, Stijn (2014). An overview of macroprudential policy tools. No. 14-214. International Monetary Fund.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2014/wp14214.pdf

Fang, Hanming, et al. (2016). “Demystifying the Chinese housing boom.” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 30.1: 105-166.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/685953

Mian, Atif, and Amir Sufi (2011). “House prices, home equity-based borrowing, and the US household leverage crisis.” American Economic Review 101.5: 2132-56.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.101.5.2132

Mian, Atif, Kamalesh Rao, and Amir Sufi (2013). “Household balance sheets, consumption, and the economic slump.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128.4: 1687-1726.

https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-pdf/128/4/1687/17094805/qjt020.pdf

Song, Zheng, Kjetil Storesletten, and Fabrizio Zilibotti (2011). “Growing like China.” American Economic Review 101.1: 196-233.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.101.1.196

Wu, Jing, Joseph Gyourko, and Yongheng Deng (2016). “Evaluating the risk of Chinese housing markets: What we know and what we need to know.” China Economic Review 39: 91-114.

House prices have become an increasingly important indicator for monitoring systemic risks and the need for macro-prudential policy measures (Claessens, 2014). While policymakers are concerned about things like the effect of high house prices on affordability or the ramifications of a burst housing bubble for household and corporate balance sheets (Mian and Sufi, 2011; Mian, Sufi, and Rao, 2013), there could also exist the very real concern of labor and capital misallocations during the run-up of house prices. The literature has looked into possible misallocations in housing booms (Charles, Hurst, and Notowidigdo, 2018; Chen and Wen, 2017; Chen et al., 2017), but it has found them to have limited discussions on productivity. Using prefecture-level official statistics, I find that cities that have experienced higher growth in residential house prices also tend to have more stagnated productivity growth in the (non-booming) non-real estate sector (Figure 1). This evidence suggests that a real estate boom could distort productivity growth in the non-booming sectors and create a “Dutch disease”-like effect.

Figure 1: House Prices and Non-Real Estate Labor Productivity

What would give rise to this effect? Misallocation of managerial talent could be one explanation. Managerial talent misallocation, in this case, meant that following the Chinese real estate boom, there were managers who moved (or reallocated their capital) to the booming real estate sector but who did not have a comparative advantage in managing real estate businesses. In an economy without barriers to entry, managers would choose projects that generate maximum returns to capital. In equilibrium, the firm decision of reallocating capital to the real estate sector would depend solely on managers’ comparative advantage. However, with financial frictions and barriers to entry into the real estate sector, managers in less wealthy firms would be constrained by the entry barrier and thus forced to stay in their original sector. A misallocation of managerial talent would occur, as long as these constrained managers do not have the comparative advantage in the original non-real estate sector.

To establish the misallocation of managerial talent, I start by looking at the patterns of capital reallocation to the real estate sector among private firms. State-owned enterprises are considered less financially constrained in China (Song, Storesletten, and Zilibotti, 2011), and they do not have a strong presence in the land market. I then formally assess the misallocation with a theoretical model and a structural estimation. I calibrate a dynamic model to quantify the aggregate loss of manufacturing total factor productivity (TFP) due to the real estate boom and, finally, analyze policy tools.

Reallocation to the Real Estate Sector

Since the early 2000s, Chinese residential house prices have persistently increased at an annual rate of more than 10% (Fang et al., 2016; Wu, Gyourko, and Deng, 2016). I find from the State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC) Firm Registration Data that a sizable number of existing private firms started operating in the real estate sector during the boom. They were involved in real estate development through either the creation of new firms or the acquisition of an existing real estate firm. Figure 2 shows the fraction of firms that had entered the real estate sector by 2010 in 18 non-real estate sectors. More than 8% of firms in sectors including utilities, financial and business services, environmental services have invested heavily in real estate.

Figure 2: Existing Firms Entry into the Real Estate Sector

Commerce and author’s calculations

The selection of private firms into the real estate sector is not random. On average, firms that began real estate businesses are larger with higher profit margins, higher credit scores, and tend to invest more in fixed assets and R&D activities. More importantly, these firms are also more productive within their original sector. Table 1 shows that a larger fraction of managers among the group that has more experience and higher levels of education entered the real estate sector during the boom. There is also a positive correlation between pre-boom TFP and the likelihood of entering the real estate sector (column (1) of Table 2), indicating that firms that produce more efficiently tend to move away from their original businesses and into the real estate business. One possible explanation is that better-performing firms could face less binding financial constraints. Controlling for firm-specific pre-boom asset value and credit score, I show in column (2) of Table 2 that the pattern in column (1) is reversed: firms with inferior performance or more inexperienced managers are more likely to start up real estate businesses in the boom given similar financing abilities.

Table 1: Fraction of Managers Entered the Real Estate Sector

Table 2: Probability of Entering the Real Estate Sector

Within private firms, the boom also led to a reallocation of capital to the real estate sector instead of a simple business expansion. Manufacturing sector investment, R&D, and labor productivity declined significantly following a firm’s entry into the real estate sector. Thus, the entries observed in Figure 2 changed the allocation of managerial talent across sectors. Admittedly, a key challenge to this argument is the possibility that declining manufacturing opportunities are what drove the real estate sector entries and explain the declining investment in the manufacturing businesses. I provide causal evidence of within-firm capital reallocation using an instrumental variables approach which exploits factors that are only crucial to real estate businesses: specifically, how managers’ possible connections with the local land bureau (based on their ethnic enclaves) interacted with local land supply constraints (following Saiz, 2010). The instrument is valid as long as manufacturing firms with better access to land are not relatively more advantageous in the manufacturing sector when land supply is adequate. Figure 3 provides the event study analyses on entering the real estate sector. The decline in labor productivity does not happen immediately after entering the real estate sector. This is likely due to the internal capital market selection, which eliminates the relatively unproductive projects within the manufacturing sector causing labor productivity to go up temporarily.

Figure 3: The Effects of Entry into the Real Estate Sector

The empirical evidence characterizes the capital reallocation decisions of private business owners and highlights the importance of financial market imperfections. Being financially constrained, a private manager would face the trade-off between real estate and manufacturing investment opportunities. Since the real estate sector is more profitable but also has a substantial entry barrier, each manager’s financing ability becomes a key determinant for starting up real estate businesses. Upon the decision to enter the real estate sector, costly land acquisitions might result in declines in investment, R&D expenditures, and productivity in firms’ manufacturing businesses.

Misallocation and Social Inefficiency

To formally establish the misallocation of managerial talent, I develop a theoretical model and structurally estimate the comparative advantage of private firm managers. The model captures the private firms’ problem: each firm’s maximum borrowing capacity increases with its net worth, and managers have heterogeneous talents in both the manufacturing sector and the real estate sector. The real estate boom in China is assumed to follow privatization in the real estate sector. After the privatization, each firm produces in the manufacturing sector and the real estate sector to maximize its profit, but the real estate sector has an entry barrier that varies with land price. In this model, a firm’s borrowing constraint implies that firm wealth was proportional to managers’ manufacturing talent before the real estate boom. When these managers’ comparative advantages lie in the manufacturing sector, a misallocation of talent occurs because the ones with a comparative advantage in the real estate sector were forced to stay outside due to a lack of wealth. In addition, given that the actual size of the entry barrier varies with land prices, there is a pecuniary externality, which leads the competitive equilibrium to deviate from the second-best scenario.

To estimate the comparative advantage of private firm managers, I revisit the firms that started conducting real estate businesses during the boom and compare their performance in both the manufacturing sector and the real estate sector. Firms with a higher average return to capital in the manufacturing sector do not generate even higher returns in the real estate sector. This evidence suggests that the wealthy and also better-performing manufacturing firms do not have a comparative advantage in the real estate sector, so they should not have moved.

The Aggregate Effect on Manufacturing Productivity Growth

To estimate the aggregate effect of the real estate boom on the productivity growth of the manufacturing sector, I generalize the theoretical model to the infinite horizon. This quantitative exercise extends the model in Song et al. (2011) by including multiple groups of entrepreneurs with heterogeneous talent and multiple sectors. My estimation shows that the real estate boom led to at least a 0.5% decline in manufacturing TFP growth, and a lower land price at the beginning of the boom due to the lack of competition in the land market.

Finally, based on the quantitative framework, I analyze three policy tools that are potentially welfare-improving: liberalizing the financial market, reducing the entry barrier in the real estate sector, and taxing the returns from operating in the real estate sector. Liberalizing the financial market, equivalent to relaxing firm borrowing constraints, improves social welfare but also aggravates social inefficiency. With more effective financial intermediaries, the already wealthy firms can borrow more, which further increases land prices. As a result, more firms with low wealth and the comparative advantage in the real estate sector are constrained by the entry barrier. Lowering the entry barrier in the real estate sector has an ambiguous impact on welfare. It creates more investment opportunities, so generally, untalented managers continue to run their businesses, resulting in a decline in total credit supply. Taxation on real estate returns can improve both social welfare and efficiency. The gains are economically significant: a 3% tax on real estate returns improves post-boom manufacturing productivity growth by 0.3% on average.

Conclusion

I show new empirical evidence that during the Chinese real estate boom, more productive manufacturing firms diverted their resources to the real estate sector, resulting in a decline in R&D, investment, and productivity growth in their manufacturing businesses. This implies a misallocation of managerial talent since the more productive managers do not have the comparative advantage in the real estate sector. A new insight emerging from this discussion is that productivity loss may exist even in the absence of a housing bubble, which differs from related works (Charles, Hurst, and Notowidigdo, 2018; Chen and Wen, 2017; Mian, Sufi, and Rao, 2013). The model can also be used to study other booming sectors, as long as they also require both a costly barrier to entry and that existing business owners reallocate from other sectors to the booming sectors. For instance, the talent misallocation channel can help examine the natural resource booms (the “Dutch disease”) observed when countries with abundant natural resources experience a significant productivity slowdown following a positive shock to commodity prices.

(Yu Shi, Economist in the IMF’s Research Department.)

Charles, Kerwin Kofi, Erik Hurst, and Matthew J. Notowidigdo (2018). “Housing booms and busts, labor market opportunities, and college attendance.” American Economic Review 108.10: 2947-94.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20151604

Chen, Kaiji, and Yi Wen (2017). “The great housing boom of China.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 9.2: 73-114.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/mac.20140234

Chen, Ting, et al. (2017). “Real Estate Boom and Misallocation of Capital in China.” Unpublished Manuscript, Princeton University.

https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=CICF2018&paper_id=915

Claessens, Stijn (2014). An overview of macroprudential policy tools. No. 14-214. International Monetary Fund.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2014/wp14214.pdf

Fang, Hanming, et al. (2016). “Demystifying the Chinese housing boom.” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 30.1: 105-166.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/685953

Mian, Atif, and Amir Sufi (2011). “House prices, home equity-based borrowing, and the US household leverage crisis.” American Economic Review 101.5: 2132-56.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.101.5.2132

Mian, Atif, Kamalesh Rao, and Amir Sufi (2013). “Household balance sheets, consumption, and the economic slump.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128.4: 1687-1726.

https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-pdf/128/4/1687/17094805/qjt020.pdf

Song, Zheng, Kjetil Storesletten, and Fabrizio Zilibotti (2011). “Growing like China.” American Economic Review 101.1: 196-233.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.101.1.196

Wu, Jing, Joseph Gyourko, and Yongheng Deng (2016). “Evaluating the risk of Chinese housing markets: What we know and what we need to know.” China Economic Review 39: 91-114.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1043951X16300384

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email