The Mandarin Model of Growth

The Mandarin model is defined by two key features of the Chinese economy. First, the government takes a central role in driving the economy through its active investment in infrastructure. Second, the agency problems between the central and local governments can lead to a rich set of phenomena in the Chinese economy--not only rapid economic growth propelled by the tournament among local governors, but also short-termist behaviors of local governors that directly affect China’s economic and financial stability.

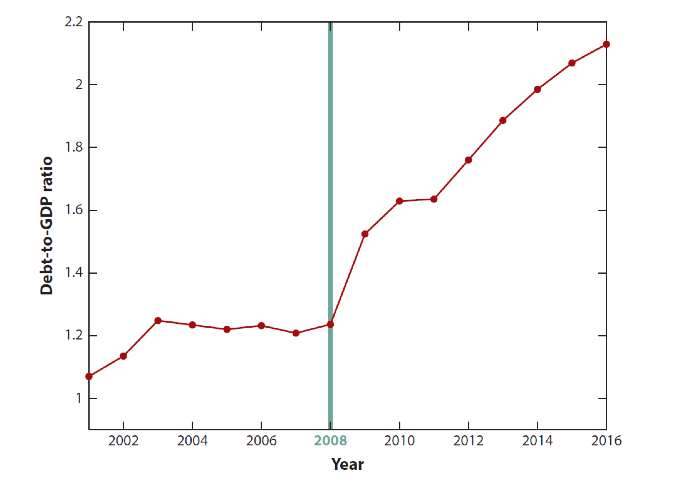

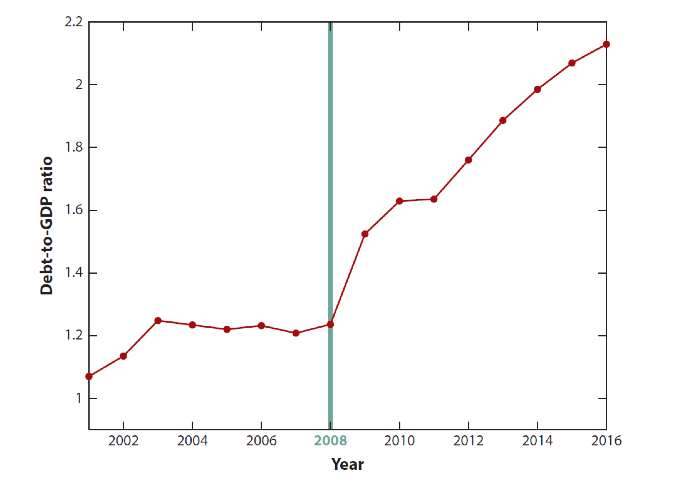

In recent years, policy makers and investment practitioners around the world have expressed growing concerns about China’s financial stability, ranging from China’s rising leverage and bubbly real estate market to its volatile capital flow and frenzied stock market [See Song and Xiong (2018) for a recent summary]. The most serious concern is related to China’s leverage. Figure 1 depicts the ratio of China’s outstanding debt (excluding the central government debt) relative to GDP between 2000 and 2016. It quickly rose above an alarming level of 2.1 in 2016, with a substantial part of the rising leverage originating from a booming shadow banking sector. This rapidly rising leverage has led to substantial concerns about a potential debt crisis in China that might eventually spill over to the rest of the world.

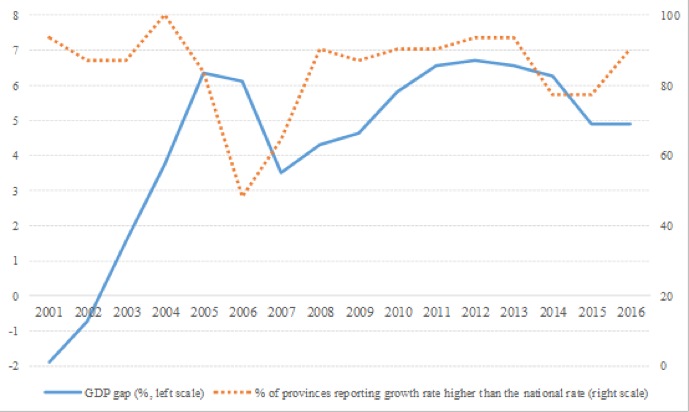

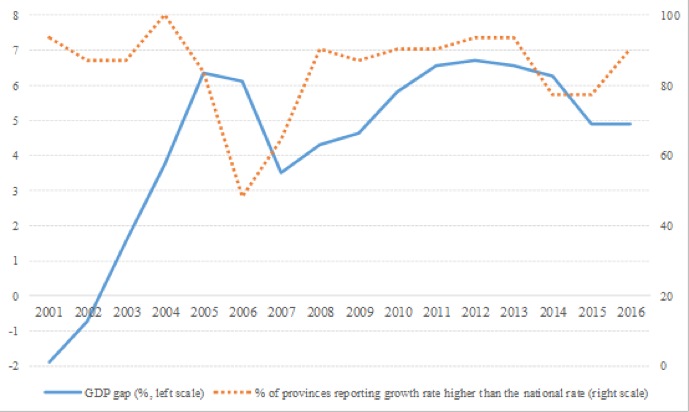

There are also widely held concerns about the reliability of China’s economic statistics. Hortacsu, Liang and Zhou (2017) and Bai et al. (2018) analyze a curious phenomenon in China’s provincial GDP. Figure 2 depicts the gap between the sum of provincial GDP (reported by provincial statistics bureaus) and the national GDP (reported by the National Bureau of Statistics) divided by the national GDP for each year in 2001-2016. Since 2004, the gap has been regularly higher than 5 percent. The figure also shows that in each year, over 80 percent of the provinces reported a GDP growth rate higher than the national growth rate, except in 2006 and 2007. This enormous discrepancy cannot simply be attributed to measurement errors and reflects a systematic issue with China’s economic statistics.

How can these concerns about China’s financial stability and economic statistics be systematically understood? It is important to recognize their common root cause in China’s government system. As pointed out by Bai, Hsieh and Song (2016) and Chen, He and Liu (2017), this leverage boom was primarily driven by China’s local governments, which only started to use debt financing from banks in 2008-2010 to implement China’s massive post-crisis stimulus program. Even though the central government discouraged local governments from any further use of debt after 2010, local governments managed to undertake even more debt, albeit from the less transparent shadow banking sector, to finance their booming investments. The discrepancy in China’s GDP statistics is related to China’s multilayered structure in reporting economic statistics: the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reports national statistics, while local statistics bureaus, which are subject to strong influence from local governments, report local statistics. Thus, the gap between the provincial GDP and the national GDP reflects systematic overreporting of the provincial governments.

To systematically analyze these issues, Xiong (2018) develops a “Mandarin model” by expanding a standard macroeconomic model to account for China’s government system. Even though the Chinese government has long abandoned central planning, it continues to play a central role in an increasingly market-driven economy, as emphasized by recent reviews of China’s economic reforms, e.g., Xu (2011) and Qian (2017). Specifically, China has a complex government system in which the central government works with regional governments at several levels: province, city, county, and township. Regional governments are major players in China’s economic development. First, regional governments carry out over 70% of fiscal spending in China and are responsible for developing economic institutions and infrastructure at the regional level, such as opening new markets and constructing roads, highways, and airports. Second, despite their autonomy in economic and fiscal issues, regional government leaders are appointed by the central government rather than being elected by the local electorate. As a key mechanism to incentivize regional leaders, the central government has established a tournament among officials across regions at the same level, promoting those who achieve fast economic growth and penalizing those who perform poorly. This system of fiscal federalism greatly stimulated China’s economic growth by giving local officials both fiscal budgets and career incentives to develop local economies. However, such powerful incentives may also lead to short-termist behaviors of local governors, as illustrated by the Mandarin model.

Specifically, the Mandarin model builds on the growth model of Barro (1990) to incorporate this institutional structure of China’s government system. The model considers an open economy with a number of regions. In each region, the representative firm has a Cobb-Douglas production function with three factors: labor, capital, and local infrastructure. By creating more infrastructure in the region, the local government can boost the productivity of the local firm. Infrastructure investment thus serves as the key channel for the local government to directly stimulate the local economy. However, the local government faces a tradeoff in allocating its fiscal budget into local infrastructure and consumption by government employees. In the absence of sufficient incentives to internalize household consumption, the local government has a tendency to underinvest in infrastructure relative to the social optimum. This underinvestment problem motivated the central government to adopt the aforementioned economic tournament—i.e., to use the output from all regions at the end of each period to jointly assess the ability and determine career advancement of all regional governors. As more investment in infrastructure improves regional output, the tournament generates an implicit incentive for each governor to invest in infrastructure through the “signal-jamming mechanism” coined by Holmstrolm (1982), due to the inability of the central government to fully separate the contribution of a governor’s ability and infrastructure investment to the regional output. This incentive serves as a powerful mechanism for driving China’s economic growth.

Furthermore, the Mandarin model shows that powerful incentives induced by the tournament may also lead local governments to engage in short-termist behaviors. First, career concerns motivate each regional governor to overreport regional output, at the expense of a higher tax transfers to the central government. This mechanism is similar in spirit to overreporting of earnings by executives of publicly listed firms, e.g., Stein (1989). Second, the tournament also motivates excessive leverage. Specifically, each regional governor faces an intertemporal tradeoff in using more debt to finance more infrastructure investment. Higher debt leads to higher growth in the current period but comes at a higher debt payment in the next period. Although a certain level of debt is socially beneficial when the local productivity growth rate is sufficiently high, a governor’s career incentives can lead to overinvestment by using excessive leverage. The model further shows that under certain assumptions, short-termist behaviors of one governor may adversely affect the relative performance evaluation of other governors, which, in turn, leads to a rat race between the governors in using leverage.

Overall, this “Mandarin” model is defined by two key features of the Chinese economy. First, the government takes a central role in driving the economy through its active investment in infrastructure, which can be interpreted more broadly as measures and policies by the government to support and stimulate economic development. Second, agency problems in the government system can lead to a rich set of phenomena in the Chinese economy—not only rapid economic growth propelled by the tournament among local governors, but also short-termist behaviors of local governors that directly affect China’s economic and financial stability.

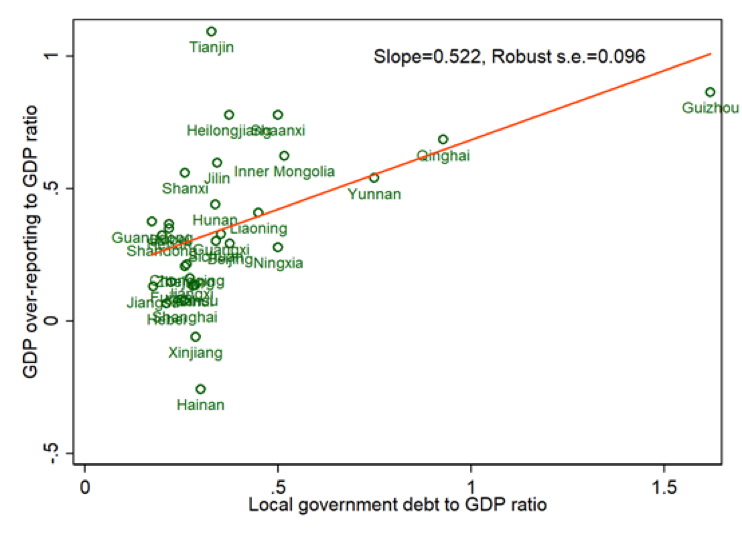

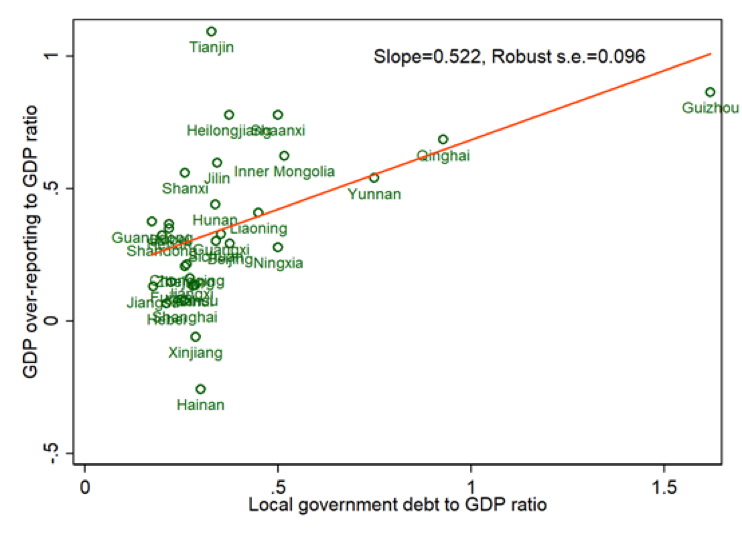

Figure 3 further highlights a strong connection in the data between two types of short-termist behaviors of local governments. Specifically, it provides a scatter plot of the ratio of provincial GDP overreporting to GDP, which is estimated by Bai et al. (2018), and local government debt-to-GDP ratio in 2015. Overall, there is an evident positive relationship between GDP overreporting and local government leverage with a t-statistic of 5.4. The literature has not previously related them with each other. In light of the Mandarin model, they may be driven by the same force—the career incentives of local governors.

Bai, Chong-En, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Song (2016), The long shadow of China’s fiscal expansion, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, 129-165.

Bai, Chong-En, Xilu Chen, Wei Chen, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Song (2018), A forensic examination of China’s national accounts, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, forthcoming.

Barro, Robert (1990), Government spending in a simple model of endogeneous growth, Journal of Political Economy 98(5, Part 2), S103-S125.

Chen, Zhuo, Zhiguo He, and Chun Liu (2017), The financing of local government in China: Stimulus loan wanes and shadow banking waxes, Working paper, University of Chicago.

Holmstrom, Bengt (1982), Managerial incentive problems: A dynamic perspective, in Essays in Economics and Management in Honor of Lars Wahlbeck, Helsinki: Swedish School of Economics.

Hortacsu, Ali, Shushu Liang, and Li-An Zhou (2017), Chinese local officials and GDP data manipulation: Evidence from night lights data, Working paper, University of Chicago and Peking University.

Qian, Yingyi (2017), How Reform Worked in China, MIT Press.

Song, Zheng and Wei Xiong (2018), Risks in China’s financial system, Annual Review of Financial Economics 10, 261-286.

Stein, Jeremy (1989), Efficient capital markets, inefficient firms: A model of myopic corporate behavior, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4), 655-669.

Xiong, Wei (2018), The Mandarin Model of Growth, Working paper, Princeton University.

In recent years, policy makers and investment practitioners around the world have expressed growing concerns about China’s financial stability, ranging from China’s rising leverage and bubbly real estate market to its volatile capital flow and frenzied stock market [See Song and Xiong (2018) for a recent summary]. The most serious concern is related to China’s leverage. Figure 1 depicts the ratio of China’s outstanding debt (excluding the central government debt) relative to GDP between 2000 and 2016. It quickly rose above an alarming level of 2.1 in 2016, with a substantial part of the rising leverage originating from a booming shadow banking sector. This rapidly rising leverage has led to substantial concerns about a potential debt crisis in China that might eventually spill over to the rest of the world.

Figure 1: Debt-to-GDP Ratio of China between 2000 and 2016.

Source: Song and Xiong (2018)

There are also widely held concerns about the reliability of China’s economic statistics. Hortacsu, Liang and Zhou (2017) and Bai et al. (2018) analyze a curious phenomenon in China’s provincial GDP. Figure 2 depicts the gap between the sum of provincial GDP (reported by provincial statistics bureaus) and the national GDP (reported by the National Bureau of Statistics) divided by the national GDP for each year in 2001-2016. Since 2004, the gap has been regularly higher than 5 percent. The figure also shows that in each year, over 80 percent of the provinces reported a GDP growth rate higher than the national growth rate, except in 2006 and 2007. This enormous discrepancy cannot simply be attributed to measurement errors and reflects a systematic issue with China’s economic statistics.

Figure 2: Provincial GDP Overreporting in China

Source: Xiong (2018)

How can these concerns about China’s financial stability and economic statistics be systematically understood? It is important to recognize their common root cause in China’s government system. As pointed out by Bai, Hsieh and Song (2016) and Chen, He and Liu (2017), this leverage boom was primarily driven by China’s local governments, which only started to use debt financing from banks in 2008-2010 to implement China’s massive post-crisis stimulus program. Even though the central government discouraged local governments from any further use of debt after 2010, local governments managed to undertake even more debt, albeit from the less transparent shadow banking sector, to finance their booming investments. The discrepancy in China’s GDP statistics is related to China’s multilayered structure in reporting economic statistics: the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reports national statistics, while local statistics bureaus, which are subject to strong influence from local governments, report local statistics. Thus, the gap between the provincial GDP and the national GDP reflects systematic overreporting of the provincial governments.

To systematically analyze these issues, Xiong (2018) develops a “Mandarin model” by expanding a standard macroeconomic model to account for China’s government system. Even though the Chinese government has long abandoned central planning, it continues to play a central role in an increasingly market-driven economy, as emphasized by recent reviews of China’s economic reforms, e.g., Xu (2011) and Qian (2017). Specifically, China has a complex government system in which the central government works with regional governments at several levels: province, city, county, and township. Regional governments are major players in China’s economic development. First, regional governments carry out over 70% of fiscal spending in China and are responsible for developing economic institutions and infrastructure at the regional level, such as opening new markets and constructing roads, highways, and airports. Second, despite their autonomy in economic and fiscal issues, regional government leaders are appointed by the central government rather than being elected by the local electorate. As a key mechanism to incentivize regional leaders, the central government has established a tournament among officials across regions at the same level, promoting those who achieve fast economic growth and penalizing those who perform poorly. This system of fiscal federalism greatly stimulated China’s economic growth by giving local officials both fiscal budgets and career incentives to develop local economies. However, such powerful incentives may also lead to short-termist behaviors of local governors, as illustrated by the Mandarin model.

Specifically, the Mandarin model builds on the growth model of Barro (1990) to incorporate this institutional structure of China’s government system. The model considers an open economy with a number of regions. In each region, the representative firm has a Cobb-Douglas production function with three factors: labor, capital, and local infrastructure. By creating more infrastructure in the region, the local government can boost the productivity of the local firm. Infrastructure investment thus serves as the key channel for the local government to directly stimulate the local economy. However, the local government faces a tradeoff in allocating its fiscal budget into local infrastructure and consumption by government employees. In the absence of sufficient incentives to internalize household consumption, the local government has a tendency to underinvest in infrastructure relative to the social optimum. This underinvestment problem motivated the central government to adopt the aforementioned economic tournament—i.e., to use the output from all regions at the end of each period to jointly assess the ability and determine career advancement of all regional governors. As more investment in infrastructure improves regional output, the tournament generates an implicit incentive for each governor to invest in infrastructure through the “signal-jamming mechanism” coined by Holmstrolm (1982), due to the inability of the central government to fully separate the contribution of a governor’s ability and infrastructure investment to the regional output. This incentive serves as a powerful mechanism for driving China’s economic growth.

Furthermore, the Mandarin model shows that powerful incentives induced by the tournament may also lead local governments to engage in short-termist behaviors. First, career concerns motivate each regional governor to overreport regional output, at the expense of a higher tax transfers to the central government. This mechanism is similar in spirit to overreporting of earnings by executives of publicly listed firms, e.g., Stein (1989). Second, the tournament also motivates excessive leverage. Specifically, each regional governor faces an intertemporal tradeoff in using more debt to finance more infrastructure investment. Higher debt leads to higher growth in the current period but comes at a higher debt payment in the next period. Although a certain level of debt is socially beneficial when the local productivity growth rate is sufficiently high, a governor’s career incentives can lead to overinvestment by using excessive leverage. The model further shows that under certain assumptions, short-termist behaviors of one governor may adversely affect the relative performance evaluation of other governors, which, in turn, leads to a rat race between the governors in using leverage.

Overall, this “Mandarin” model is defined by two key features of the Chinese economy. First, the government takes a central role in driving the economy through its active investment in infrastructure, which can be interpreted more broadly as measures and policies by the government to support and stimulate economic development. Second, agency problems in the government system can lead to a rich set of phenomena in the Chinese economy—not only rapid economic growth propelled by the tournament among local governors, but also short-termist behaviors of local governors that directly affect China’s economic and financial stability.

Figure 3: Provincial GDP Overreporting Versus Local Government Leverage

Source: Xiong (2018)

Figure 3 further highlights a strong connection in the data between two types of short-termist behaviors of local governments. Specifically, it provides a scatter plot of the ratio of provincial GDP overreporting to GDP, which is estimated by Bai et al. (2018), and local government debt-to-GDP ratio in 2015. Overall, there is an evident positive relationship between GDP overreporting and local government leverage with a t-statistic of 5.4. The literature has not previously related them with each other. In light of the Mandarin model, they may be driven by the same force—the career incentives of local governors.

(Wei Xiong, Department of Economics, Princeton University.)

Bai, Chong-En, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Song (2016), The long shadow of China’s fiscal expansion, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, 129-165.

Bai, Chong-En, Xilu Chen, Wei Chen, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Song (2018), A forensic examination of China’s national accounts, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, forthcoming.

Barro, Robert (1990), Government spending in a simple model of endogeneous growth, Journal of Political Economy 98(5, Part 2), S103-S125.

Chen, Zhuo, Zhiguo He, and Chun Liu (2017), The financing of local government in China: Stimulus loan wanes and shadow banking waxes, Working paper, University of Chicago.

Holmstrom, Bengt (1982), Managerial incentive problems: A dynamic perspective, in Essays in Economics and Management in Honor of Lars Wahlbeck, Helsinki: Swedish School of Economics.

Hortacsu, Ali, Shushu Liang, and Li-An Zhou (2017), Chinese local officials and GDP data manipulation: Evidence from night lights data, Working paper, University of Chicago and Peking University.

Qian, Yingyi (2017), How Reform Worked in China, MIT Press.

Song, Zheng and Wei Xiong (2018), Risks in China’s financial system, Annual Review of Financial Economics 10, 261-286.

Stein, Jeremy (1989), Efficient capital markets, inefficient firms: A model of myopic corporate behavior, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4), 655-669.

Xiong, Wei (2018), The Mandarin Model of Growth, Working paper, Princeton University.

Xu, Chenggang (2011), The fundamental institutions of China’s reforms and development, Journal of Economic Literature 49(4), 1076-1151.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email