The Impact of Corporate Taxes on Firm Innovation: Evidence from the Corporate Tax Collection Reform in China

We explore a tax reform on manufacturing firms in China in order to

study the impact of taxes on firm innovation. The reform switched

corporate income tax collection from a local to state tax bureau and

reduced the effective tax rate by 10 percent. The reform only applied to

firms established after January 2002, allowing us to use a regression

discontinuity design as the identification strategy. The results show

that lower taxes improved both the quantity and quality of firm

innovation. Moreover, the reform had a bigger impact on firms that are

financially constrained and firms that engage more in tax evasion.

Innovation has been increasingly recognized as the main engine for economic growth (Romer, 1990; Aghion and Howitt, 1992; Aghion, Akcigit, and Howitt, 2014). To escape the middle-income trap, China’s government launched various policies to stimulate research and development (R&D) activities (Chen et al., 2018). However, we know very little about its impact of such policies on firm innovation and the underlying mechanisms (Ufuk et al., 2018; Djankov et al., 2011).

Theoretically, taxes can have either positive or negative impacts on firm innovation. On the one hand, lower taxes can increase the after-tax profit of firms, so that they have a better capacity to invest in new technologies or products. Moreover, lower taxes may reduce the resources that firms spend on tax evasion, such as the cost of bribing tax officers, which can be instead used on innovation activities. On the other hand, lower taxes may also have a negative impact on innovation because they decrease government revenue, and in turn may reduce government spending on public goods such as research, education, and infrastructure. As a result, it is unclear whether tax incentives improve firm innovation.

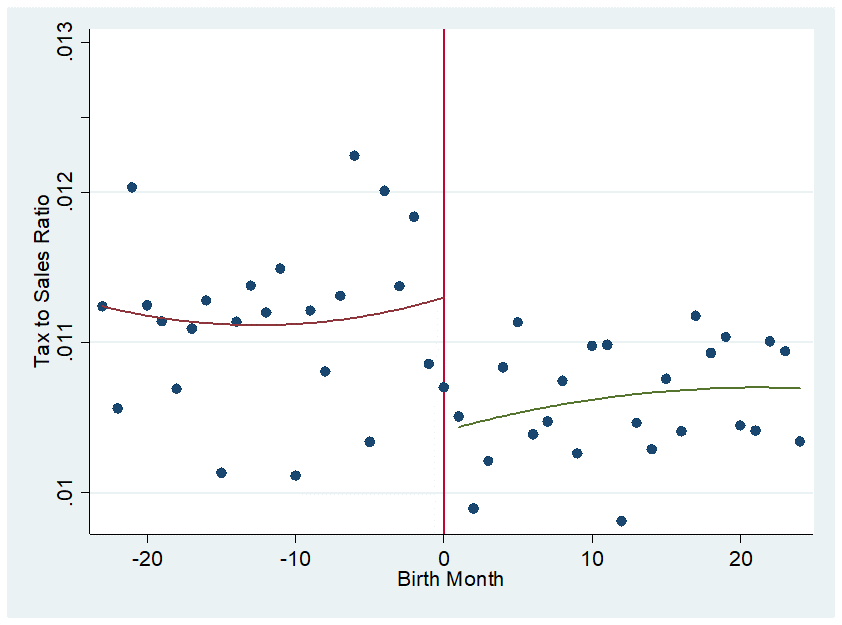

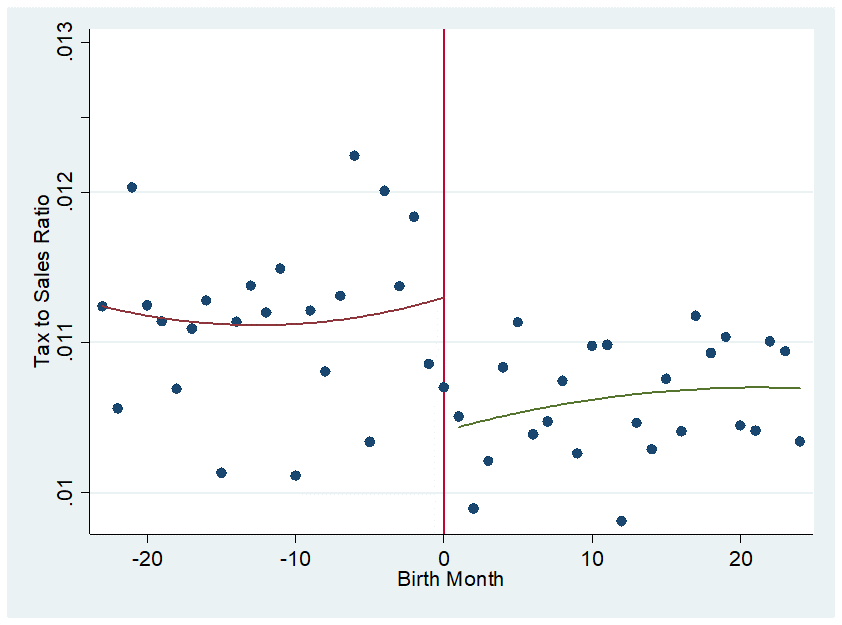

In this study, we investigate the impact of taxes on firm innovation using a natural experiment in China. In November 2001, China implemented a tax collection reform on all manufacturing firms established on or after January 2002, which switched the collection of corporate income taxes from a local tax bureau to a state tax bureau. After the reform, firms established before 2002 paid very different effective tax rates than firms established after 2002 due to the differences in the management of and incentives offered by the two types of tax bureaus. Figure 1 shows that the reform changed the enforcement of tax collection, resulting in a reduction of effective corporate income tax rates by almost 10 percent among newly established firms. Since firms registered before 2002 were not affected by the reform, the policy change created exogenous variations in the effective tax rate among similar firms established before and after 2002. We can thus apply a regression discontinuity design (RD) and use the generated variation in the effective tax rate to identify the impact of taxes on firm innovation.

To test the impact of taxes on innovation, we combine a comprehensive dataset of all medium and large enterprises in China in business between 1998 and 2007 with patent data from the State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) including all patents applied for in China by the year 2014. We use the data to measure three dimensions of innovation activities: input (R&D expenditure and skilled labor ratio), output (number of patent applications), and quality (type and characteristics of patent application).

The key assumption of the RD analysis is that a firm cohort should have a significant impact on the effective corporate tax rate; however, all other unobserved determinants of firm innovation are not correlated with the firm cohort. We provide three pieces of evidence to validate the estimation strategy. First, the reform significantly reduced the effective tax rate: the tax rate is almost 10 percent lower among firms established after 2002 compared with those registered before 2002. Second, there is no significant difference in firm entry around 2002, suggesting that the reform was a surprise to firms and they did not selectively postpone their registration date. Third, there is not a significantly higher rate of firm re-registration after 2002.

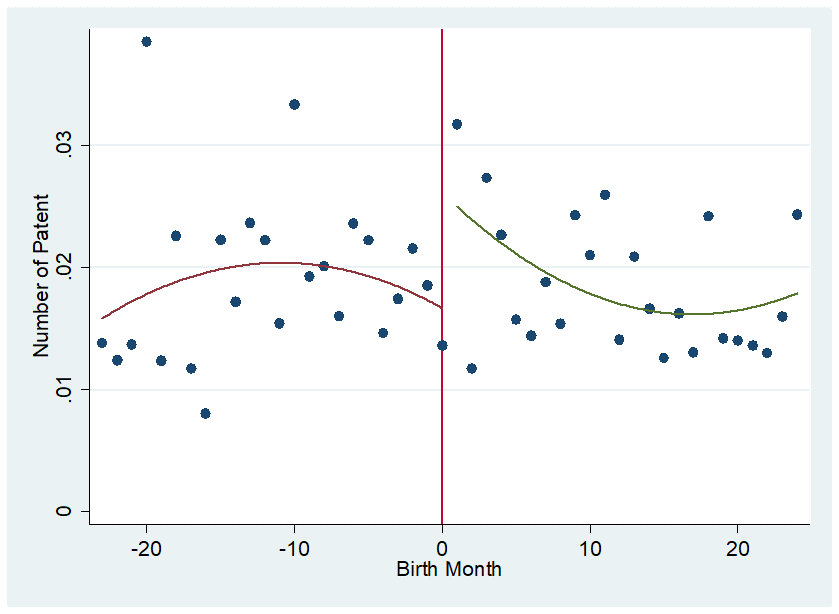

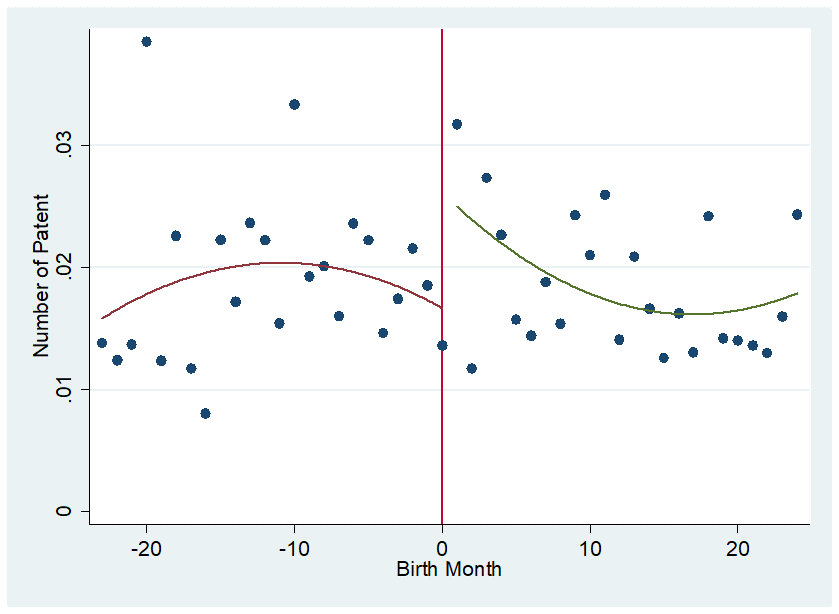

Our analysis yields several interesting results. First, we show a strong and robust causal relationship between the tax rate and firm innovation: decreasing the effective tax rate by one standard deviation (0.01) increases the average number of patent applications by a significant 5.7 percent (see Figure 2 for the graphical evidence). The reform also stimulated R&D expenditures and increased the skilled-labor ratio by 14 percent. Second, a lower tax rate also improved the quality of the patents. The impact of tax reform on patent applications mainly originates from its effect on invention and utility patents: decreasing the effective tax rate by one standard deviation improves the probability of having an invention patent application by 4.4 percent and increases the number of utility patent applications by 4.7 percent. This suggests that the improvement in innovation outcomes is not merely driven by the low-quality design patents. We also use the detailed information of patent applications as proxies for the patent quality, including the number of overall claims, number of independent claims, and the amount of effort that was spent on the patent application (based on the length of the application document, number of figures, and length of abstract). In our patent data, only invention and utility patents have the above information and results suggest that a reduction in the tax rate significantly improved patent quality; the effect is significant for both invention and utility patents.

Note: This figure is based on data in the year 2007 and compares the number of patent applications (weighted by firm size) by firms established before and after the policy change. Birth month of firms established in January 2002 is normalized to 0.

Furthermore, we try to study why firm innovation is affected by the tax reform. We test two potential mechanisms in the paper: a financial constraint channel and a tax evasion channel. First, we test whether reducing tax costs can help by alleviating financial constraints; allowing firms to use the money saved to carry out innovation activities. Under a neoclassical framework, if R&D expenditure is fully deductible, the tax rate should not affect innovation since it does not change the after-tax marginal benefit and cost of innovation. However, when the financial market is incomplete or inefficient and a firm mostly relies on its own after-tax profit, a lower effective tax rate could affect innovation investment. We use the interest payment as the proxy for the degree of financial constraint and provide suggestive evidence that a low tax rate can stimulate a firm’s innovation by alleviating financial constraints.

Second, in principal, a lower effective tax rate may also release resources that firms spend on tax avoidance, which firms can in turn use on innovation. To test this potential channel, we follow Cai and Liu (2009) to measure tax evasion activity and find firms that are involved in more tax evasion and can therefore release more resources for innovation after the reform.

This paper contributes to the existing literature in several ways. While there are a growing number of papers studying the impact of taxes on firm decision-making, we are among the first to analyze the effect of corporate taxes on firm innovation in China. More importantly, we are the first paper to look at the impact of the changes in tax enforcement rather than the explicit tax reduction on firms’ innovation behavior. This paper also contributes to the literature on tax enforcement. The tax-to-GDP ratio is substantially lower in poor countries compared with developed countries. One important reason for low tax revenue is weak tax enforcement. Our study adds to the tax enforcement literature by showing that the management of and incentives offered by tax collection agencies play an important role in tax enforcement and the tax capacity of a country.

Aghion, Philippe, and Peter Howitt, “A Model of Growth through Creative Destruction,” Econometrica 60:2 (1992): 323-351.

Aghion, Philippe, Ufuk Akcigit, and Peter Howitt, “What Do We Learn from Schumpeterian Growth Theory?”. In the Handbook of Economic Growth. Edited by Philippe Aghion and Steven N. Furlauf. Edition 1, Volume 2, 515-563. Amsterdam, North Holland: Elsevier, 2014.

Akcigit, Ufuk, John Grigsby, Tom Nicholas, and Stepanie Stantcheva, “Taxation and Innovation in the 20th Century,” NBER Working Paper No. 24982, 2018.

Cai, Jing , Yuyu Chen, and Xuan Wang, “The Impact of Corporate Taxes on Firm Innovation: Evidence from the Corporate Tax Collection Reform in China” NBER Working Paper No. 25146, 2018.

Cai, Hongbin, and Qiao Liu, “Competition and Corporate Tax Avoidance: Evidence from Chinese Industrial Firms,” Economic Journal 119 (2009): 764-795.

Chen, Zhao, Juan Carlos Suarez Serrato, Zhikuo Liu, and Daniel Yi Xu, “Notching R&D Investment with Corporate Income Tax Cuts in China,” NBER Working Paper No. 24749, 2018.

Djankov, Simeon, Tim Ganser, Caralee McLiesh, Rita Ramalho, and Andrei Shleifer, “The Effect of Corporate Taxes on Investment and Entrepreneurship,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2:3 (2011): 31–64.

Innovation has been increasingly recognized as the main engine for economic growth (Romer, 1990; Aghion and Howitt, 1992; Aghion, Akcigit, and Howitt, 2014). To escape the middle-income trap, China’s government launched various policies to stimulate research and development (R&D) activities (Chen et al., 2018). However, we know very little about its impact of such policies on firm innovation and the underlying mechanisms (Ufuk et al., 2018; Djankov et al., 2011).

Theoretically, taxes can have either positive or negative impacts on firm innovation. On the one hand, lower taxes can increase the after-tax profit of firms, so that they have a better capacity to invest in new technologies or products. Moreover, lower taxes may reduce the resources that firms spend on tax evasion, such as the cost of bribing tax officers, which can be instead used on innovation activities. On the other hand, lower taxes may also have a negative impact on innovation because they decrease government revenue, and in turn may reduce government spending on public goods such as research, education, and infrastructure. As a result, it is unclear whether tax incentives improve firm innovation.

In this study, we investigate the impact of taxes on firm innovation using a natural experiment in China. In November 2001, China implemented a tax collection reform on all manufacturing firms established on or after January 2002, which switched the collection of corporate income taxes from a local tax bureau to a state tax bureau. After the reform, firms established before 2002 paid very different effective tax rates than firms established after 2002 due to the differences in the management of and incentives offered by the two types of tax bureaus. Figure 1 shows that the reform changed the enforcement of tax collection, resulting in a reduction of effective corporate income tax rates by almost 10 percent among newly established firms. Since firms registered before 2002 were not affected by the reform, the policy change created exogenous variations in the effective tax rate among similar firms established before and after 2002. We can thus apply a regression discontinuity design (RD) and use the generated variation in the effective tax rate to identify the impact of taxes on firm innovation.

Figure 1: Effective Tax Rate by Firms’ Birth Month

Note: This figure is based on data in the year 2007 and compares the effective tax rate (defined as corporate income tax to sales ratio) paid by firms established before and after the policy change. The birth month of firms established in January 2002 is normalized to 0.

To test the impact of taxes on innovation, we combine a comprehensive dataset of all medium and large enterprises in China in business between 1998 and 2007 with patent data from the State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) including all patents applied for in China by the year 2014. We use the data to measure three dimensions of innovation activities: input (R&D expenditure and skilled labor ratio), output (number of patent applications), and quality (type and characteristics of patent application).

The key assumption of the RD analysis is that a firm cohort should have a significant impact on the effective corporate tax rate; however, all other unobserved determinants of firm innovation are not correlated with the firm cohort. We provide three pieces of evidence to validate the estimation strategy. First, the reform significantly reduced the effective tax rate: the tax rate is almost 10 percent lower among firms established after 2002 compared with those registered before 2002. Second, there is no significant difference in firm entry around 2002, suggesting that the reform was a surprise to firms and they did not selectively postpone their registration date. Third, there is not a significantly higher rate of firm re-registration after 2002.

Our analysis yields several interesting results. First, we show a strong and robust causal relationship between the tax rate and firm innovation: decreasing the effective tax rate by one standard deviation (0.01) increases the average number of patent applications by a significant 5.7 percent (see Figure 2 for the graphical evidence). The reform also stimulated R&D expenditures and increased the skilled-labor ratio by 14 percent. Second, a lower tax rate also improved the quality of the patents. The impact of tax reform on patent applications mainly originates from its effect on invention and utility patents: decreasing the effective tax rate by one standard deviation improves the probability of having an invention patent application by 4.4 percent and increases the number of utility patent applications by 4.7 percent. This suggests that the improvement in innovation outcomes is not merely driven by the low-quality design patents. We also use the detailed information of patent applications as proxies for the patent quality, including the number of overall claims, number of independent claims, and the amount of effort that was spent on the patent application (based on the length of the application document, number of figures, and length of abstract). In our patent data, only invention and utility patents have the above information and results suggest that a reduction in the tax rate significantly improved patent quality; the effect is significant for both invention and utility patents.

Figure 2: Number of Patent Applications by Firms’ Birth Month

Furthermore, we try to study why firm innovation is affected by the tax reform. We test two potential mechanisms in the paper: a financial constraint channel and a tax evasion channel. First, we test whether reducing tax costs can help by alleviating financial constraints; allowing firms to use the money saved to carry out innovation activities. Under a neoclassical framework, if R&D expenditure is fully deductible, the tax rate should not affect innovation since it does not change the after-tax marginal benefit and cost of innovation. However, when the financial market is incomplete or inefficient and a firm mostly relies on its own after-tax profit, a lower effective tax rate could affect innovation investment. We use the interest payment as the proxy for the degree of financial constraint and provide suggestive evidence that a low tax rate can stimulate a firm’s innovation by alleviating financial constraints.

Second, in principal, a lower effective tax rate may also release resources that firms spend on tax avoidance, which firms can in turn use on innovation. To test this potential channel, we follow Cai and Liu (2009) to measure tax evasion activity and find firms that are involved in more tax evasion and can therefore release more resources for innovation after the reform.

This paper contributes to the existing literature in several ways. While there are a growing number of papers studying the impact of taxes on firm decision-making, we are among the first to analyze the effect of corporate taxes on firm innovation in China. More importantly, we are the first paper to look at the impact of the changes in tax enforcement rather than the explicit tax reduction on firms’ innovation behavior. This paper also contributes to the literature on tax enforcement. The tax-to-GDP ratio is substantially lower in poor countries compared with developed countries. One important reason for low tax revenue is weak tax enforcement. Our study adds to the tax enforcement literature by showing that the management of and incentives offered by tax collection agencies play an important role in tax enforcement and the tax capacity of a country.

(Jing Cai, University of Maryland; Yuyu Chen, Guanghua School of Management, Peking University; Xuan Wang, University of Michigan.)

Aghion, Philippe, and Peter Howitt, “A Model of Growth through Creative Destruction,” Econometrica 60:2 (1992): 323-351.

Aghion, Philippe, Ufuk Akcigit, and Peter Howitt, “What Do We Learn from Schumpeterian Growth Theory?”. In the Handbook of Economic Growth. Edited by Philippe Aghion and Steven N. Furlauf. Edition 1, Volume 2, 515-563. Amsterdam, North Holland: Elsevier, 2014.

Akcigit, Ufuk, John Grigsby, Tom Nicholas, and Stepanie Stantcheva, “Taxation and Innovation in the 20th Century,” NBER Working Paper No. 24982, 2018.

Cai, Jing , Yuyu Chen, and Xuan Wang, “The Impact of Corporate Taxes on Firm Innovation: Evidence from the Corporate Tax Collection Reform in China” NBER Working Paper No. 25146, 2018.

Cai, Hongbin, and Qiao Liu, “Competition and Corporate Tax Avoidance: Evidence from Chinese Industrial Firms,” Economic Journal 119 (2009): 764-795.

Chen, Zhao, Juan Carlos Suarez Serrato, Zhikuo Liu, and Daniel Yi Xu, “Notching R&D Investment with Corporate Income Tax Cuts in China,” NBER Working Paper No. 24749, 2018.

Djankov, Simeon, Tim Ganser, Caralee McLiesh, Rita Ramalho, and Andrei Shleifer, “The Effect of Corporate Taxes on Investment and Entrepreneurship,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2:3 (2011): 31–64.

Romer, Paul, “Endogenous Technological Change,” Journal of Political Economy 98 (1990): 71-102.

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email