Measuring Chinese Shadow Banking: Banks’ Shadow and Traditional Shadow Banking

Chinese shadow banking is dominated by commercial banks, due to the bank-dominated financial system in China. A key characteristic of shadow banking in China is that banks hide loans as alternative accounting subjects. Motivated by this important characteristic, this article distinguishes Banks’ Shadow from Traditional Shadow Banking (mainly non-bank financial institutions), from the perspective of the bank’s credit money creation. I investigate specific channels that contribute to both Banks' Shadow and Traditional Shadow Banking, providing accurate measurements and analyzing the evolution of these channels as banks respond to government regulations. As a resulting policy implication, I emphasize that regulators should apply different restrictions on Banks' Shadow and Traditional Shadow Banking, and focus on the balance sheet items that banks might use for hiding their shadow banking operations.

Banks’ Shadow entails banking activities which provide funding for real sectors through asset expansion (which is inherently identical to bank loans) and related credit money creation (asset expansion simultaneously creates deposits), but which circumvents regulatory restrictions—such as credit allocation constraints—by hiding loans as alternative balance-sheet items. Banks’ Shadow is mainly channeled through third-party financial institutions, including other banks and non-bank financial institutions.

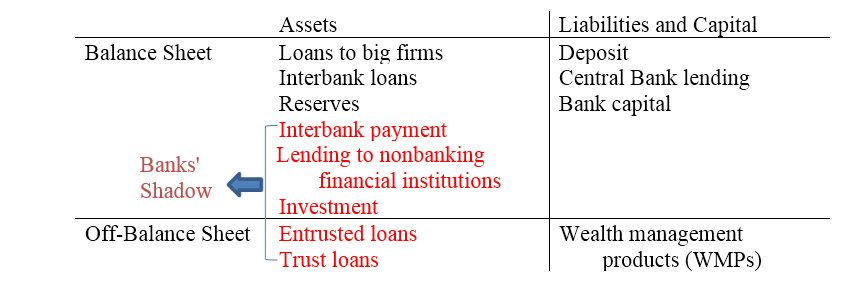

Figure 1 shows the main balance-sheet items and off-balance-sheet items (i.e., shadow banking related) of state banks in China. Banks’ Shadow, which creates money supply, includes the following on-balance-sheet and off-balance-sheet items: interbank payment (同业代付), lending to nonbanking financial institutions (同业拆放), investment (投资), entrusted loans (委托贷款), and trust loans by bank-trust cooperation (银信合作). Note that around 70% (estimated) of trust funds in China are originated by banks and further granted as trust loans through bank-trust-cooperation. (NB: In China, the trust company license allows participation in money market business, capital market business, and alternative investments. Trust companies can lend to restricted or high-risk industries (e.g., real estate, local government financing platforms (LGFP)) and are subject to less scrutiny, as they only act on behalf of their beneficiaries.)

Caution should be paid to wealth management products (WMPs), which lie on the liabilities side of the balance sheet. WMPs are “quasi-deposits,” which are effectively bank products sold to households. In the case of loans to local government financing platforms, state banks tend to move these loans off balance sheet as entrusted loans, and the corresponding deposits also off balance sheet as WMPs. This means that the money created by Banks’ Shadow should be canceled. The returns of WMPs are generally higher than deposit rates. For example, in June 2017, the average yield of a WMP was 4.66% (annualized), while the official deposit rate was 1.5%. The reasons for higher WMP returns include the fact that 1) WMPs are not subject to reserve requirements, and 2) WMPs are not covered by deposit insurance.

Traditional Shadow Banking involves credit creation activities undertaken by non-bank financial institutions, and it transfers money outside the banking system to provide funding for enterprises. It has similar credit creation mechanisms as in advanced economies. Without acting as a channel for banks, non-bank financial institutions invest funds that they raise to real sectors through trust loans (without bank-trust cooperation), asset management plans, equipment leasing, mortgages, credit loans, etc. In this process, credit increases but money supply remains unchanged, and it is only a transformation of money between different entities.

Funding from China’s shadow banking mainly flows into three types of borrowers, namely local government funding platforms (LGFP), enterprises with excess capacity, and real estate developers. For the purpose of illustrating the financing process, take channels of Banks’ Shadow as examples. State banks could lend to nonbanking financial institutions (同业拆放), which then lend to LGFP, enterprises with over-capacity, and real estate developers as entrusted loans. This is driven by the fact that risk weight for lending to financial institutions is lower than to enterprises. Besides, state banks could also provide loans indirectly to enterprises through small banks, by holding the claim to small banks as interbank payment. This is motivated by a regulation that the credit risk weight of interbank payment is 25%, which is much less than the 100% for loans to enterprises. Moreover, banks purchase financial products issued by non-banking financial institutions including trust companies, security firms, insurance companies, financial companies, and mutual fund (subsidiary companies), which again have lower risk weight than loans. The corresponding balance sheet items mainly include 1) receivable investment (the beneficial rights of trust, commercial paper, and bond) and 2) financial assets available for sale.

The fast growth of Chinese shadow banking has been largely stimulated by credit tightening policies introduced in 2010 and driven by China’s unique banking regulation system. In the second quarter of 2010, Chinese monetary authorities began to implement prudent monetary policy, introduced macro-prudential policies characterized by capital constraints to strengthen regulation, and applied specific credit regulations to sectors that have excess capacity (e.g., real estate). To circumvent regulations and meet financing need in certain sectors, shadow banking activities rose sharply, thus posing threats to financial stability.

The effectiveness of some regulatory policies and tools has been compromised or partially offset by the shadow banking system. For example, the Chinese government set credit limitations—such as on loans from traditional banks and the equity ratio of developers—on the real estate sector in order to prevent housing bubbles, but shadow banking provides alternative funding resources. A similar case holds for enterprises with excess capacity. Furthermore, the capital adequacy requirement for banks became less effective, since shadow banking activities enabled banks to move some assets off-balance sheet, such as entrusted loans and trust loans through bank-trust cooperation, as mentioned above.

Accurate measurements of China’s shadow banking with all of its channels are fundamental for banking supervision and regulation. It is important, therefore, to avoid double counting. As indicated in Figure 1, bank-trust-cooperation related bank assets overlap with trust loans. Double counting happens if one sums up trust loans and WMPs, since trust loans are on the asset side while WMPs are on the liability side.

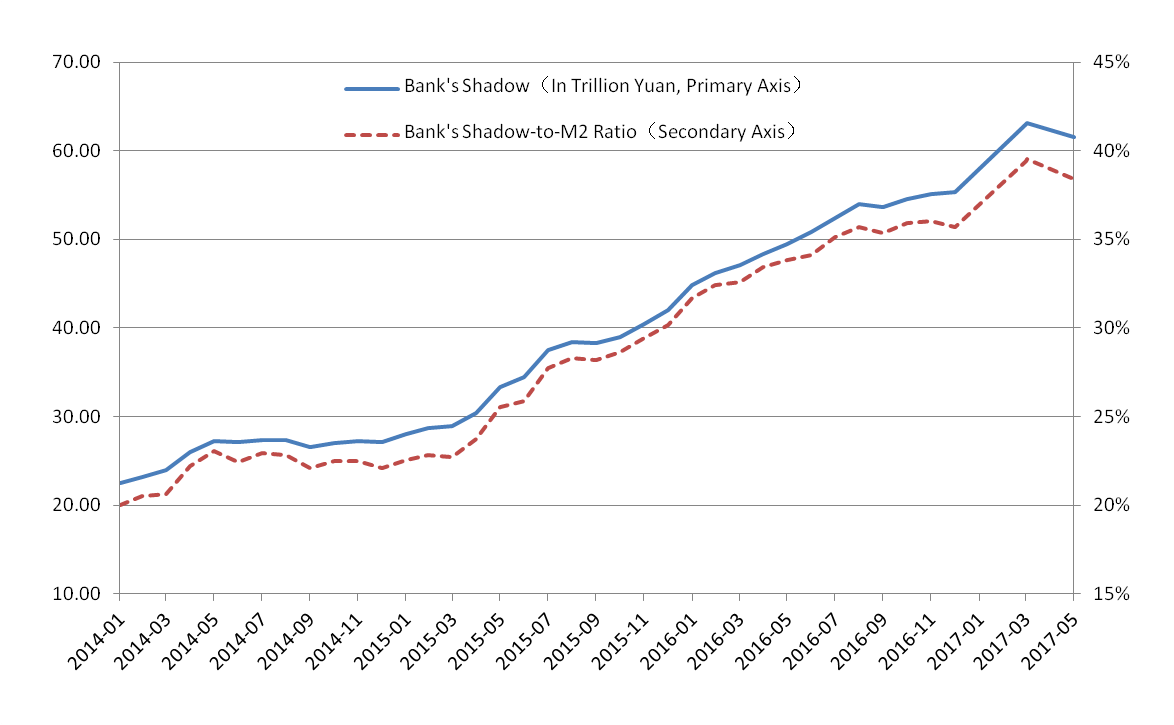

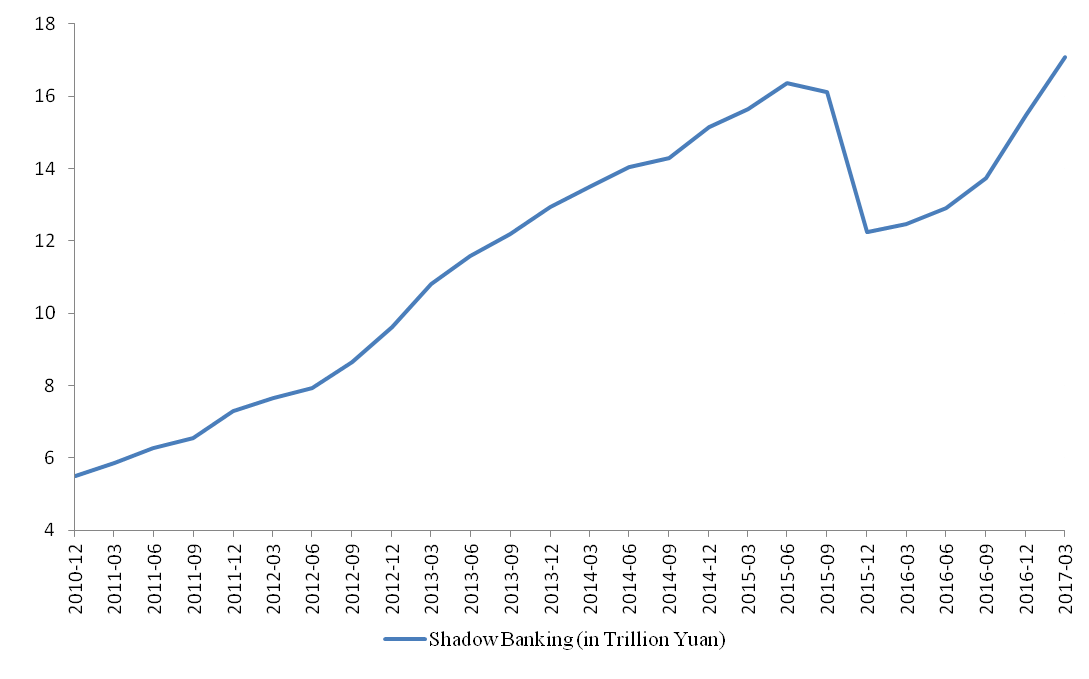

Following approaches introduced by Sun and Jia (2015), I measure Banks’ Shadow with the deduction method and apply direct counting for estimating Traditional Shadow Banking. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show not only the evolution of Chinese shadow banking (both Banks' Shadow and Traditional Shadow Banking), but also the impacts of regulations on banks’ active responses in switching among various Banks’ Shadow channels.

As illustrated in Figure 2, between June and December 2014, the scale of Banks’ Shadow and its proportion in money creation declined (Panel A), and this is mainly due to the shrinkage in Banks’ Shadow that channeled through other banks, such as interbank payment and reverse repo (Panel B). Ultimately, this is due to stricter regulations on interbank business that were implemented by Chinese financial market regulators. During January 2015 through December 2016, although the volume of reverse repo kept declining, Banks’ Shadow picked up its momentum in growth and the ensuing credit money contributed to an increasing proportion in total credit money creation by banks. These trends indicate that banks switch from the reverse repo channel to alternative channels to hide assets, such as financial assets available for sale and receivable investments (Panel B). (NB: Banks are required to consolidate all bank-trust-cooperation WMPs on balance sheet.)

Compared with Banks’ Shadow, China's Traditional Shadow Banking is relatively small (Panel A of Figure 3). Among channels of Traditional Shadow Banking, trust assets take the largest share, and their contraction led to a sharp drop in the scale of Traditional Shadow Banking in 2015. This contraction of trust assets was due to stricter regulations (e.g., capital requirements, etc.) on trust companies imposed by Chinese financial market regulators.

Panel A: Size of Banks’ Shadow in China (Unit: Trillion Yuan)

To further strengthen the supervision of shadow banking, separate tools are needed to implement macro-prudential regulations of Banks’ Shadow and Traditional Shadow Banking. Regulators should impose an "Asset Reserve" requirement on banks and a “risk reserve” requirement on non-bank financial institutions. The “Asset Reserve” requirement requests banks to hold deposit at central bank according to the amount of banks’ assets. This requirement pays attention to the asset side of a bank’s balance sheet, compared to the existing reserve requirement which focuses on the liability side of a bank’s balance sheet; is based on risk characteristics of different bank assets; and can control not only asset risk but also money creation from bank assets (not liabilities), thus improving the efficiency of monetary policy transmission. The “Risk Reserve” requirement compels non-bank financial institutions to hold deposits at central bank according to the amount of fundings that they absorb in order to cope with liquidity risk. Because non-bank financial insitutions can only use their fundings to provide credit to enterprises, and can not creat credit through assets expansion, so this requirement can bind the credit creation of Traditional Shadow Banking to the balance sheet of monetary authorities, effectively restraining credit creation of non-bank financial institutions. Equipped with these two kinds of institutional arrangements, a generalized macro-prudential regulation framework could be erected. Combining this framework with other policies, such as micro-prudential regulations, would form a comprehensive law and regulation system for shadow banking supervision.

To summarize, my analysis of China’s shadow banking system highlights the important role of Banks’ Shadow in the credit money creation process, which poses challenges to monetary policy regulation and financial risk management. I urge regulators to closely track the evolution of various shadow banking channels both on- and off-balance sheet. To strengthen supervision, separate macro-prudential regulation tools are needed for Banks’ Shadow and Traditional Shadow Banking, respectively.

(Sun Guofeng is now the Director General of the Research Institute of the People’s Bank of China.)

Sun, G. and Jia, J. (2015). “Definition and Measurement of China’s Shadow Banking:From the Perspective of Credit Money Creation,”Social Sciences in China, 2015(11): 92-110. http://voxchina.org/show-55-40.html

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email