Accounting for Urban China’s Rising Income Inequality: The Roles of the Labor Market, Human Capital, and Marriage Market Factors

China has witnessed persistent increases in economic inequality since the early 1990s when the urban labor market began its transformation — from centrally-controlled to market-driven. Using the Urban Household Survey data, this paper (Feng and Tang, 2018) documents the trends in income inequality over the period of 1992-2009 and decomposes changes in income inequality by considering three main factors: the labor market, human capital, and marriage market. We find that labor market factors account for approximately three-quarters of the overall increases in income inequality while the falling marriage rate has contributed the other quarter. Changes in human capital levels and marital assortativeness have not contributed to the rising inequality.

Family income inequality in urban China has persistently and significantly increased from 1992-2009. Based on our calculations using the Urban Household Survey (UHS) data, the Gini coefficient for urban China has risen from 0.266 to 0.407 (by 53 percent). P90/P10, which is the ratio of the 90th percentile and the 10th percentile family incomes, respectively, has increased even more — from 3.2 to 8.6, or by 169 percent. Meanwhile, China has also experienced drastic changes in many aspects of its society and economy. During this time, China’s economic system has been transformed from centrally-planned to market-oriented and Chinese society has been significantly modernized. It is expected that many of these changes would inevitably trigger increased inequality. It is therefore important to understand what factors (and to what extent) have shaped economic inequality during this process of industrialization, marketization, and modernization.

We classify various underlying drivers of income distribution into three broad categories: labor market, human capital, and marriage market — all of which have experienced considerable changes during our study period. First, beginning in the early 1990s, economic restructuring has fundamentally transformed China’s urban labor market, which affects people’s employment status and returns to observed and unobserved skills. Second, levels of human capital have increased significantly during this period due to the college enrollment expansion program started in 1999. Last, but not least, since individual incomes are shared within a family, changes in the marriage market, including whether people marry and whom they marry, are also potentially important determinants of family income inequality.

The paper extends the new methodology proposed by Eika et al. (2014), which expounds upon the work of DiNardo et al. (1996). The idea is to hold the distribution of one factor fixed at the base period, while letting the distribution of other factors vary over time to obtain the counterfactual distribution of family income. By comparing the counterfactual income inequality measures with the actual ones, we are then able to assess how family income inequality has been affected by the changes in the specific factors considered.

Structural Changes in the Labor Market are the Key to Understanding China’s Rising Income Inequality

We further differentiate labor market factors into employment, returns to education, and within-education-group inequality. During our study period, the state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform, the introduction of the first labor law, and the increase in rural-to-urban migration together transformed China's urban labor market into one that is mainly market-driven. The reforms in the urban labor market significantly increased returns to observed and unobserved skills, which led to higher between-education-group and within-education group inequalities. In addition, people from low-income families have experienced more employment declines as they are more likely to be adversely affected by the structural changes in the labor market. This also leads to higher family income inequality.

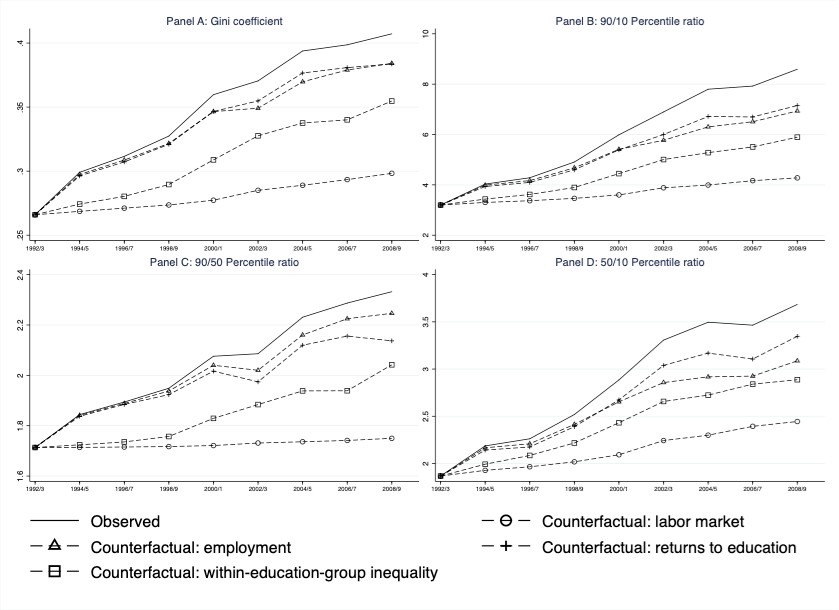

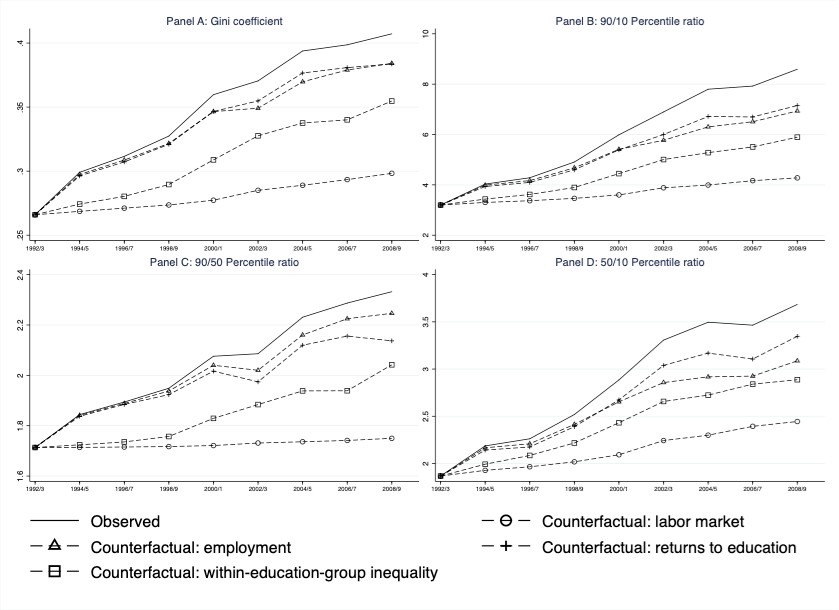

Our results suggest that labor market factors are most important to the increases in family income inequality during the 1992-2009 period. Figure 1 shows that if allthree of the factors are held unchanged at the levels of 1992/93, the Gini coefficient would only increase from 0.266 to 0.298, instead of to the actual 0.407. Therefore, labor market factors collectively contribute more than three-quarters of the total increase in inequality. Further, labor market factors are more important in affecting the upper part of the income distribution as they account for almost all of the changes in P90/P50, the ratio of the 90th percentile to median family incomes.

A more careful examination suggests that each labor market factor plays an important role. Changes in employment and returns to education both contribute about 16 percent of the change in inequality over the study period, while within-education-group inequality accounts for around 37 percent of the overall increase in inequality. Therefore, within-education-group inequalities are not only crucial in changes to individual income inequality, as many previous researchers have noted, but are also important in the rise in regards to family income inequality.

Note: Figure 5 in Feng and Tang (2018). This figure displays actual and counterfactual time trends in family income inequality from 1992/93 to 2008/09. The solid lines show the Gini coefficient/income differentials in the actual distribution of household income. The dashed lines show counterfactual income inequalities in various scenarios.

The Declining Marriage Rate Contributes to the Rising Inequality

For marriage market factors, we consider both the marriage rate (of females) and educational assortative mating. Educational assortative mating is measured as marital sorting parameters; i.e., the ratio of the observed probability that a husband with a given education level is married to a wife with a given education level to the probability under random matching. It is well-known that China has experienced a delay in ages at first marriage and a decline of the marriage rate in the last few decades. Also, changes in educational assortative mating (individuals sorting into internally homogeneous marriages) also affect family inequality as education is one of the most important predictors of income.

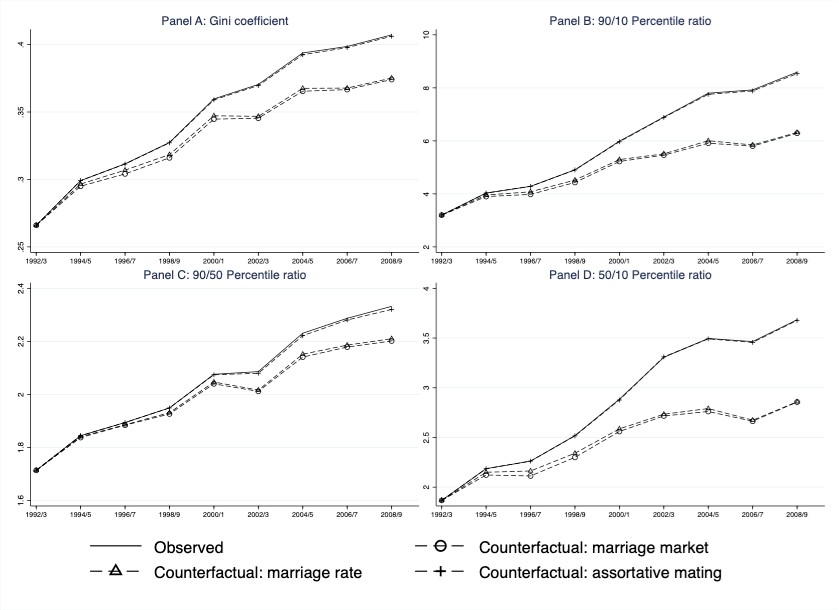

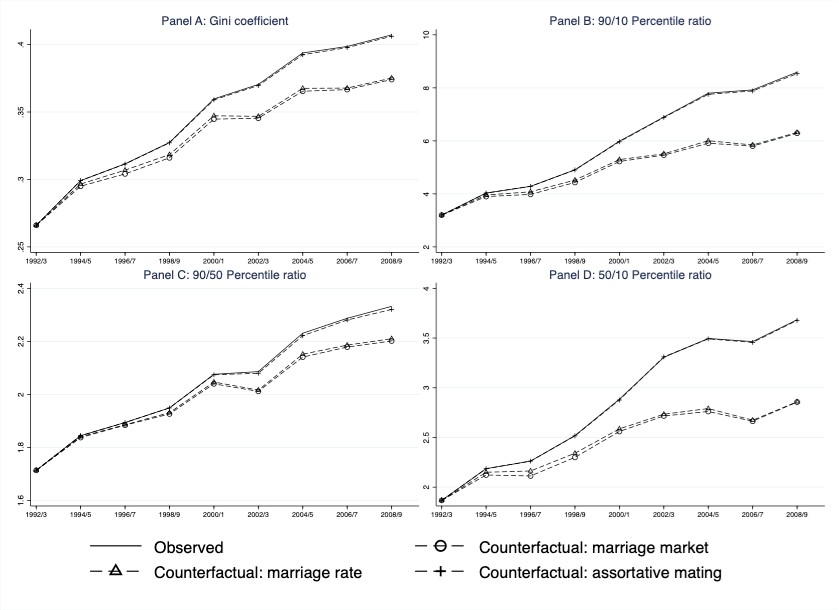

Our results show that marriage market factors account for about one-quarter of the increase in the Gini coefficient. Figure 2 shows that the effects are mostly due to the declining marriage rate rather than changes in educational assortative mating, which contributes almost nothing. The declining marriage rate is also more important in the lower part of the income distribution as measured by P50/P10, the ratio of the median to the 10th percentile family incomes. As shown in Panel A of Figure 2, marriage market factors collectively contribute nearly one-quarter of the increase in the Gini coefficient during the 1992-2009 period. Also, as Panel D shows, marriage rate changes contribute almost half of the increase in the lower part inequality as measured by P50/P10. We also find that changes in assortative mating play almost no role in the change in family income inequality. This finding is also similar to what Eika et al. (2014) demonstrated for the United States. Therefore, policymakers should pay special attention to the declining marriage rates for males and females with low levels of education.

Notes: Figure 10 in Feng and Tang (2018). This figure displays actual and counterfactual time trends in family income inequality from 1992/93 to 2008/09. The solid lines show the Gini coefficient/income differentials in the actual distribution of household income. The dashed lines show counterfactual income inequalities in various scenarios.

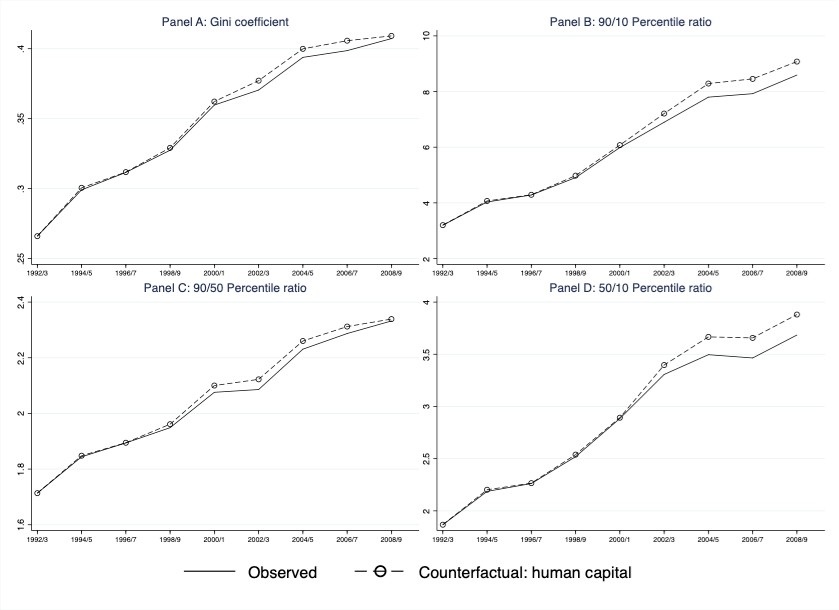

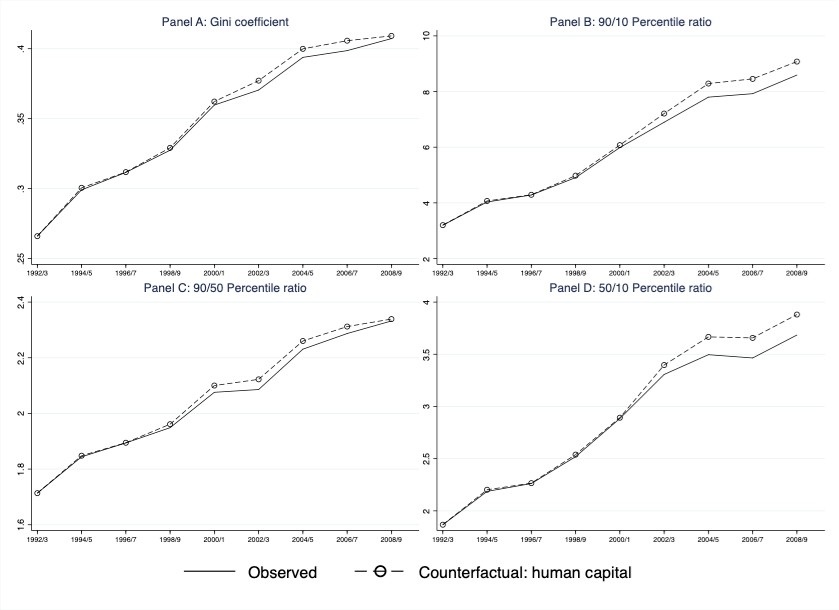

Last, we explore the effect of changes in human capital, as the levels of educational attainment have increased significantly during this period due to the college enrollment expansion program started in 1999. Figure 3 shows that despite the significant increases in educational attainments, changes in human capital have only contributed to offsetting the rising inequality in family income, although the effects are very small. This is understandable as the distribution of education or educational inequality has not changed much despite the general increases in the levels of education. The results are very similar when percentile ratios are used. In addition, it seems that education expansion has improved the lower part of the income distribution as measured by the P50/P10 index in Panel D of Figure 3.

Note: Figure 7 in Feng and Tang (2018). This figure displays actual and counterfactual time trends in family income inequality from 1992/93 to 2008/09. The solid lines show the Gini coefficient/income differentials in the actual distribution of household income. The dashed lines show counterfactual income inequalities when the education distribution is held constant at the initial levels.

The Northeast has Gone from the Most Equal Region to the Most Unequal Region

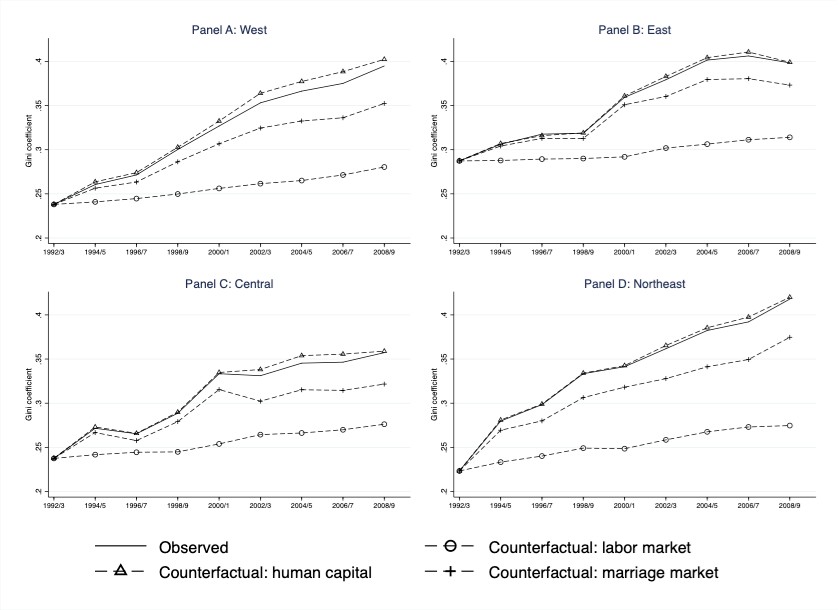

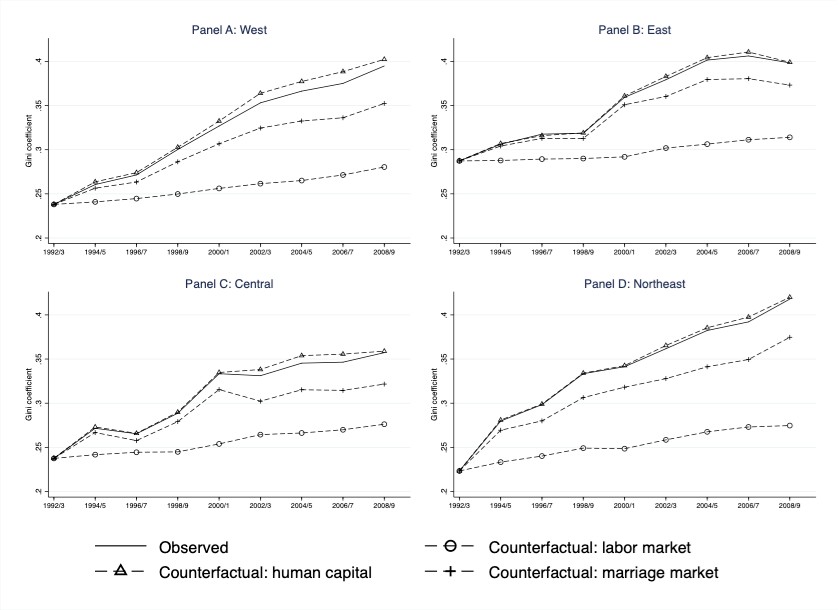

As China is a country with considerable regional heterogeneities, it is important to examine whether different regions have different inequality trends and underlying drivers of inequality. This is particularly relevant given that some previous studies have listed regional differences as one of the most important contributors to China’s overall inequality. We divide China into four regions: East, West, Central, and Northeast. For each region, we show inequality trends and contributions from the labor market, human capital, and marriage market factors (Figure 4). First, it is important to note that all of the regions have witnessed considerable increases in inequality. The main drivers of rising inequality are labor market factors, followed by marriage market factors, while human capital has played no role. Therefore, our national results are not driven by peculiarities from any particular region. Second, there are some differences across regions. For example, the Northeast has gone from the most equal region to the most unequal region during 1992-2009. This is actually consistent with our main hypothesis that economic restructuring has been the fundamental driver of rising inequality in China during the post-1990s period. The Northeast region was traditionally dominated by heavy industry and was the hardest-hit area during the SOE reform period (Feng et al., 2017). From 1995-2002, 7.3 million workers were laid off in the Northeast region, accounting for 42 percent of its total SOE employment in 1995.

Note: Figure 11 in Feng and Tang (2018). This figure displays actual and counterfactual time trends in family income inequality from 1992/93 to 2008/09. The solid lines show the Gini coefficient/income differentials in the actual distribution of household income. The dashed lines show counterfactual income inequalities in various scenarios.

DiNardo, J., N. Fortin, and T. Lemieux (1996). “Labor Market Institutions and the Distribution of Wages, 1973-1992: A Semiparametric Approach,” Econometrica64(5): 1001-1044. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2171954?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Eika, L., M. Mogstad, and B. Zafar (2014). “Educational Assortative Mating and Household Income Inequality,” NBER working paper No. 20271. https://www.nber.org/papers/w20271

Feng, S., Y. Hu, and R. Moffitt (2017). “Long-run Trends in Unemployment and Labor Force Participation in Urban China,” Journal of Comparative Economics 45 (2): 304–324. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0147596717300227

Family income inequality in urban China has persistently and significantly increased from 1992-2009. Based on our calculations using the Urban Household Survey (UHS) data, the Gini coefficient for urban China has risen from 0.266 to 0.407 (by 53 percent). P90/P10, which is the ratio of the 90th percentile and the 10th percentile family incomes, respectively, has increased even more — from 3.2 to 8.6, or by 169 percent. Meanwhile, China has also experienced drastic changes in many aspects of its society and economy. During this time, China’s economic system has been transformed from centrally-planned to market-oriented and Chinese society has been significantly modernized. It is expected that many of these changes would inevitably trigger increased inequality. It is therefore important to understand what factors (and to what extent) have shaped economic inequality during this process of industrialization, marketization, and modernization.

We classify various underlying drivers of income distribution into three broad categories: labor market, human capital, and marriage market — all of which have experienced considerable changes during our study period. First, beginning in the early 1990s, economic restructuring has fundamentally transformed China’s urban labor market, which affects people’s employment status and returns to observed and unobserved skills. Second, levels of human capital have increased significantly during this period due to the college enrollment expansion program started in 1999. Last, but not least, since individual incomes are shared within a family, changes in the marriage market, including whether people marry and whom they marry, are also potentially important determinants of family income inequality.

The paper extends the new methodology proposed by Eika et al. (2014), which expounds upon the work of DiNardo et al. (1996). The idea is to hold the distribution of one factor fixed at the base period, while letting the distribution of other factors vary over time to obtain the counterfactual distribution of family income. By comparing the counterfactual income inequality measures with the actual ones, we are then able to assess how family income inequality has been affected by the changes in the specific factors considered.

Structural Changes in the Labor Market are the Key to Understanding China’s Rising Income Inequality

We further differentiate labor market factors into employment, returns to education, and within-education-group inequality. During our study period, the state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform, the introduction of the first labor law, and the increase in rural-to-urban migration together transformed China's urban labor market into one that is mainly market-driven. The reforms in the urban labor market significantly increased returns to observed and unobserved skills, which led to higher between-education-group and within-education group inequalities. In addition, people from low-income families have experienced more employment declines as they are more likely to be adversely affected by the structural changes in the labor market. This also leads to higher family income inequality.

Our results suggest that labor market factors are most important to the increases in family income inequality during the 1992-2009 period. Figure 1 shows that if allthree of the factors are held unchanged at the levels of 1992/93, the Gini coefficient would only increase from 0.266 to 0.298, instead of to the actual 0.407. Therefore, labor market factors collectively contribute more than three-quarters of the total increase in inequality. Further, labor market factors are more important in affecting the upper part of the income distribution as they account for almost all of the changes in P90/P50, the ratio of the 90th percentile to median family incomes.

A more careful examination suggests that each labor market factor plays an important role. Changes in employment and returns to education both contribute about 16 percent of the change in inequality over the study period, while within-education-group inequality accounts for around 37 percent of the overall increase in inequality. Therefore, within-education-group inequalities are not only crucial in changes to individual income inequality, as many previous researchers have noted, but are also important in the rise in regards to family income inequality.

Figure 1: The Roles of Labor Market Factors

Note: Figure 5 in Feng and Tang (2018). This figure displays actual and counterfactual time trends in family income inequality from 1992/93 to 2008/09. The solid lines show the Gini coefficient/income differentials in the actual distribution of household income. The dashed lines show counterfactual income inequalities in various scenarios.

The Declining Marriage Rate Contributes to the Rising Inequality

For marriage market factors, we consider both the marriage rate (of females) and educational assortative mating. Educational assortative mating is measured as marital sorting parameters; i.e., the ratio of the observed probability that a husband with a given education level is married to a wife with a given education level to the probability under random matching. It is well-known that China has experienced a delay in ages at first marriage and a decline of the marriage rate in the last few decades. Also, changes in educational assortative mating (individuals sorting into internally homogeneous marriages) also affect family inequality as education is one of the most important predictors of income.

Our results show that marriage market factors account for about one-quarter of the increase in the Gini coefficient. Figure 2 shows that the effects are mostly due to the declining marriage rate rather than changes in educational assortative mating, which contributes almost nothing. The declining marriage rate is also more important in the lower part of the income distribution as measured by P50/P10, the ratio of the median to the 10th percentile family incomes. As shown in Panel A of Figure 2, marriage market factors collectively contribute nearly one-quarter of the increase in the Gini coefficient during the 1992-2009 period. Also, as Panel D shows, marriage rate changes contribute almost half of the increase in the lower part inequality as measured by P50/P10. We also find that changes in assortative mating play almost no role in the change in family income inequality. This finding is also similar to what Eika et al. (2014) demonstrated for the United States. Therefore, policymakers should pay special attention to the declining marriage rates for males and females with low levels of education.

Figure 2: The Roles of Marriage Market Factors

Notes: Figure 10 in Feng and Tang (2018). This figure displays actual and counterfactual time trends in family income inequality from 1992/93 to 2008/09. The solid lines show the Gini coefficient/income differentials in the actual distribution of household income. The dashed lines show counterfactual income inequalities in various scenarios.

Last, we explore the effect of changes in human capital, as the levels of educational attainment have increased significantly during this period due to the college enrollment expansion program started in 1999. Figure 3 shows that despite the significant increases in educational attainments, changes in human capital have only contributed to offsetting the rising inequality in family income, although the effects are very small. This is understandable as the distribution of education or educational inequality has not changed much despite the general increases in the levels of education. The results are very similar when percentile ratios are used. In addition, it seems that education expansion has improved the lower part of the income distribution as measured by the P50/P10 index in Panel D of Figure 3.

Figure 3: The Roles of Human Capital Factors

Note: Figure 7 in Feng and Tang (2018). This figure displays actual and counterfactual time trends in family income inequality from 1992/93 to 2008/09. The solid lines show the Gini coefficient/income differentials in the actual distribution of household income. The dashed lines show counterfactual income inequalities when the education distribution is held constant at the initial levels.

The Northeast has Gone from the Most Equal Region to the Most Unequal Region

As China is a country with considerable regional heterogeneities, it is important to examine whether different regions have different inequality trends and underlying drivers of inequality. This is particularly relevant given that some previous studies have listed regional differences as one of the most important contributors to China’s overall inequality. We divide China into four regions: East, West, Central, and Northeast. For each region, we show inequality trends and contributions from the labor market, human capital, and marriage market factors (Figure 4). First, it is important to note that all of the regions have witnessed considerable increases in inequality. The main drivers of rising inequality are labor market factors, followed by marriage market factors, while human capital has played no role. Therefore, our national results are not driven by peculiarities from any particular region. Second, there are some differences across regions. For example, the Northeast has gone from the most equal region to the most unequal region during 1992-2009. This is actually consistent with our main hypothesis that economic restructuring has been the fundamental driver of rising inequality in China during the post-1990s period. The Northeast region was traditionally dominated by heavy industry and was the hardest-hit area during the SOE reform period (Feng et al., 2017). From 1995-2002, 7.3 million workers were laid off in the Northeast region, accounting for 42 percent of its total SOE employment in 1995.

Figure 4: Results by Region

Note: Figure 11 in Feng and Tang (2018). This figure displays actual and counterfactual time trends in family income inequality from 1992/93 to 2008/09. The solid lines show the Gini coefficient/income differentials in the actual distribution of household income. The dashed lines show counterfactual income inequalities in various scenarios.

(Shuaizhang Feng, Institute for Economic and Social Research, Jinan University; Gaojie Tang, School of Economics, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics.)

DiNardo, J., N. Fortin, and T. Lemieux (1996). “Labor Market Institutions and the Distribution of Wages, 1973-1992: A Semiparametric Approach,” Econometrica64(5): 1001-1044. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2171954?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

Eika, L., M. Mogstad, and B. Zafar (2014). “Educational Assortative Mating and Household Income Inequality,” NBER working paper No. 20271. https://www.nber.org/papers/w20271

Feng, S., Y. Hu, and R. Moffitt (2017). “Long-run Trends in Unemployment and Labor Force Participation in Urban China,” Journal of Comparative Economics 45 (2): 304–324. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0147596717300227

Feng, S., and G. Tang (2018). “Accounting for Urban China’s Rising Income Inequality: The Roles of Labor Market, Human Capital, and Marriage Market Factors,” Economic Inquiry, forthcoming. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ecin.12748?af=R

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email