Gender-Targeted Job Ads: Patterns, Impacts, and Mechanisms

Gender-targeted job ads are common in many emerging economies. Using data from jobboards—which differ substantially in terms of culture, size, and user groups targeted—our empirical evidence suggests that policies that target workers’ application decisions may be at least as important as policies that target employers’ screening decisions, if not more.

Gender-targeted job ads are common in many emerging economies. This article summarizes several of our recent studies on this subject. We find that explicit gender preferences in job ads 1) favor women about as frequently as men; 2) are much less common in jobs with high skill requirements; 3) vary substantially within firms but less within jobs, and 4) ‘tilt’ strongly towards men as workers get older. Besides employers’ job posting behavior, we have also examined workers’ application behavior and employers’ call-back behavior in the presence of gendered job ads.

Using data from a Chinese job board, we find that 1) job ads’ explicit gender preferences can account for 59% of the eventual gender segregation across jobs in our data; 2) most of this gender segregation can be accounted for by gender preference-linked self-selection in the application stage; and 3) job ads’ explicit gender preferences are very effective in directing workers’ application behavior. Furthermore, the impact of explicit gender preferences is strongest when the jobs’ titles are least likely to be interpreted as preferring the applicant’s gender. Interestingly, women are much less likely to apply than men when jobs don’t explicitly request their gender. These findings suggest that policies that target workers’ application decisions are at least as important as policies that target employers’ screening decisions, if not more.

Introduction

There is a huge literature on gender discrimination and inequality in the labor market (i.e., Blau and Kahn, 2017, and Goldin, 2014). While it is undeniable that the job search and matching process plays a pivotal role in gender inequality in the labor market, there have not been many studies from the search-and-matching perspective due to data availability constraints. But the increasing usage of online job boards in the past decade has largely alleviated such constraints. We use online job board data to examine gender targeted job ads in a series of recent studies.

The practice of stating an explicit gender preference in job ads is widely used in emerging economies. In China, the earliest regulation that we are aware of that specifically prohibits gender discrimination by labor market intermediaries is the Ministry of Labor and Social Security’s Regulations on Employment Service and Employment Management issued in 2007. However, enforcement of anti-discrimination laws at that time is widely perceived to have been weak. Gendered job ads largely disappeared from national job boards only after China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology issued a regulation aimed directly at gendered job ads on online job platforms in 2016. Nonetheless, in China such ads are still common in many local and smaller job boards. On the other hand, even in countries where gender discrimination is illegal, employers are now able to limit exposure of their job ads to their preferred worker types with the help of targeted advertising (Angwin, Scheiber and Tobin, 2017). Together, these observations indicate that employers’ discriminatory behavior demands continuous attention.

When we examine the labor market at a granular level, the agents in the labor market are obviously not matched with each other randomly. Instead, employers and workers strategically search and match over time through a three-stage dynamic process. First, employers decide on the content of job ads. Then workers decide on the set of jobs for which they apply. Finally, employers decide on the set of workers to interview and hire. In this process, employers’ job posting decisions on whether or not to include an explicit gender preference in the job ads initiates the whole dynamic of gender segregation. The impacts of employers’ gender requests depend on the responsiveness of workers as well as employers’ enforcement at the screening stage.

Here, we shall summarise the main findings of our studies on explicit gender preferences in job ads in terms of patterns, impacts, and mechanisms. A brief discussion of the policy implications of our studies will conclude this article.

1. Patterns

Using job posting data from four online job boards, Kuhn and Shen (2013) and Delgado Helleseter et al. (forthcoming) establish four major patterns of employers’ explicit gender preferences:

• Symmetry: The shares of job ads that request men and women roughly equal each other.

• Negative skill-targeting: Job ads requesting less education, less experience, and offering lower wages are more likely to express a gender preference. This applies to requests both for men and for women.

• Job- (rather than firm-) specificity: Whether a job ad requests a man or a woman is more closely linked to the type of work to be done than the identity of the firm posting the ad. In fact, it is common for the same employer to request men for some jobs and women for others.

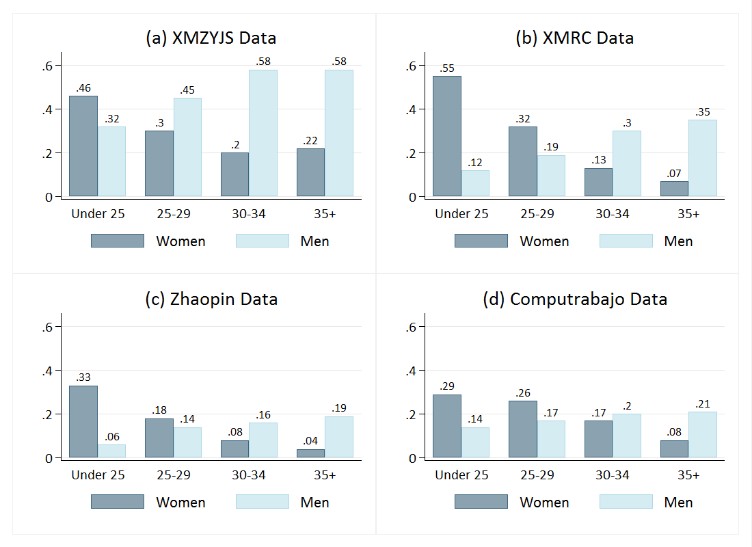

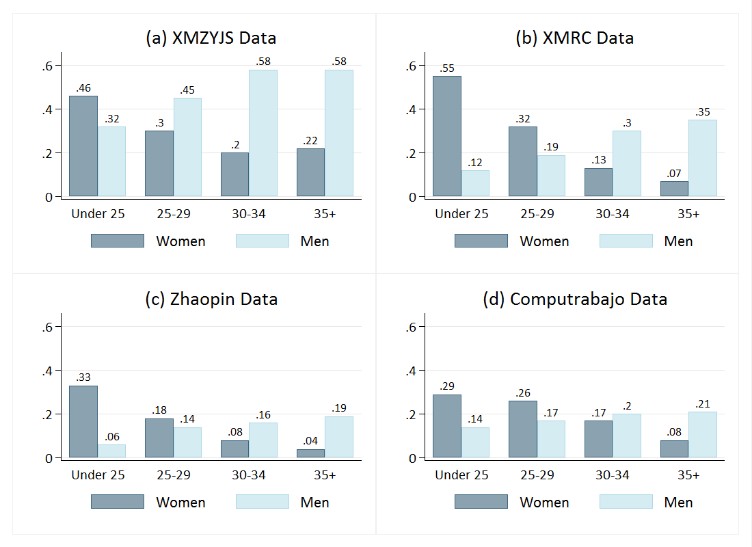

• The ‘age twist’: As the desired worker age rises between 18 and 45, employers’ advertised gender requests ‘flip’ from strongly favoring women to strongly favoring men. Figure 1 provides descriptive evidence of such age-twist patterns.

Note: This is Figure 2 of Delgado Helleseter et al. (forthcoming). The bars indicate the shares of job ads requesting women and men in each of the four desired age groups (under 25, 25-29, 30-34, and 35+).

To further understand the age twist in employers’ gender preferences, we use the information contained in job titles as well as nationally representative survey datasets of China and Mexico, and find that:

• 65% of the age twist can be ‘explained’ by age-related changes in the mix of tasks. In particular, employers tend to prefer young women for ‘helping’, customer contact, and administrative occupations, while preferring older men for managerial jobs.

• Employers’ preferences for young women and employers’ preferences for beauty are strongly, and positively, correlated.

• Employers’ gender-specific preferences for workers’ marital and fertility status also contribute to the age twist. Specifically, employers prefer single women and women without children, while preferring married men and men with children.

It is worth noting that the four online job boards we study—Zhaopin.com (a national job board in China), XMRC.com (a city level job board targeting white-collar jobs), XMZYJS.com (a city level job board targeting blue-collar jobs), and Computrabajo-Mexico (a national job board in Mexico)—differ substantially in terms of culture, size, and user groups targeted. Nonetheless, evidence from all four of these job boards support the above patterns.

2. Impacts and Mechanisms

Recently, our research has shifted to the second and third stages of the search and matching process. It is worth noting that workers’ application behavior and employers’ job posting and call back behavior are assumed to depend on each other in our setup. Such assumptions are supported by several empirical studies (i.e., Banfi and Villena-Roldan, 2018, and Niederle and Lise, 2007).

Specifically, Kuhn et al. (2018) examine the impacts of employers’ explicit gender preferences and the related mechanisms.

Using internal data provided by XMRC.com, they find that:

• 92.4% of applications and 94.8% of call-backs to gendered job ads are from (for) the requested gender.

• When considering all job ads (whether or not they have explicit gender preferences), 50-60% of the gender segregation among successful job applicants can be accounted for by job ads’ gender preferences.

Our decomposition exercises further suggest that most of the impact of gender preferences can be accounted for by workers’ application behavior, rather than employers’ call back behavior. While gender-mismatched applicants do suffer from substantial penalties in terms of callback chances, 74% of the observed matching between employer’s gender requests and successful applicants’ gender is due to workers’ self-selection at the application stage.

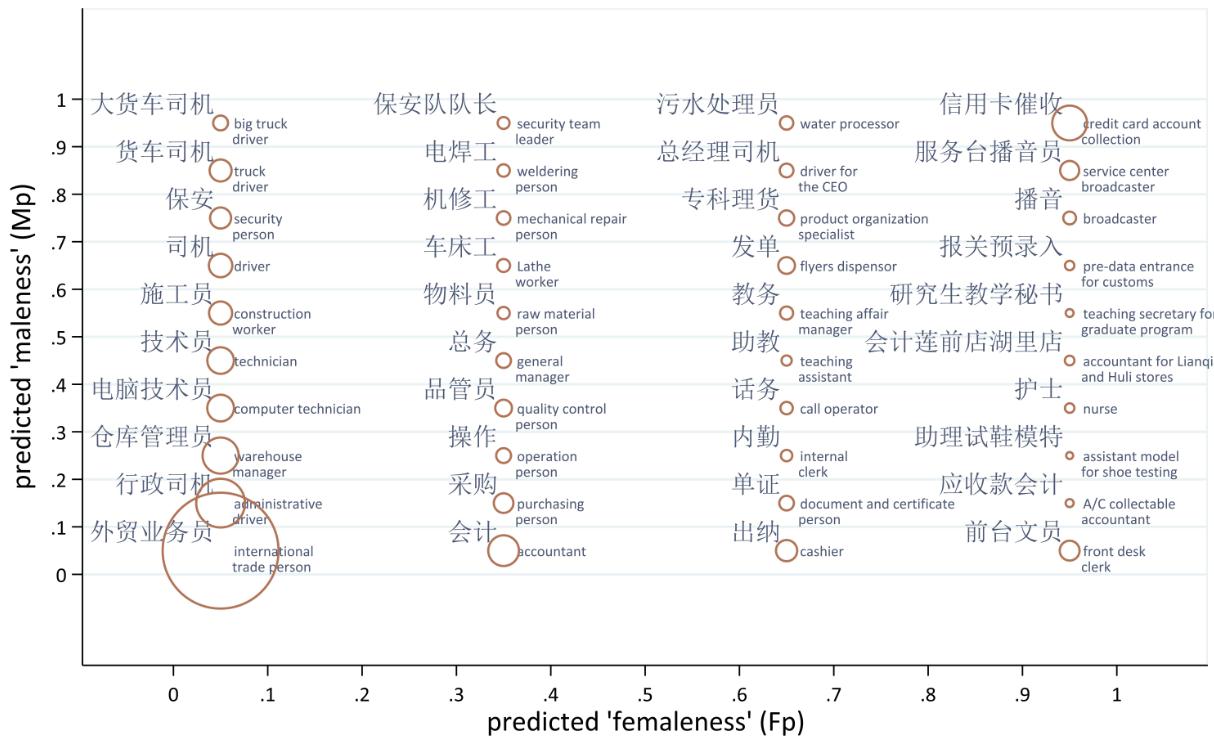

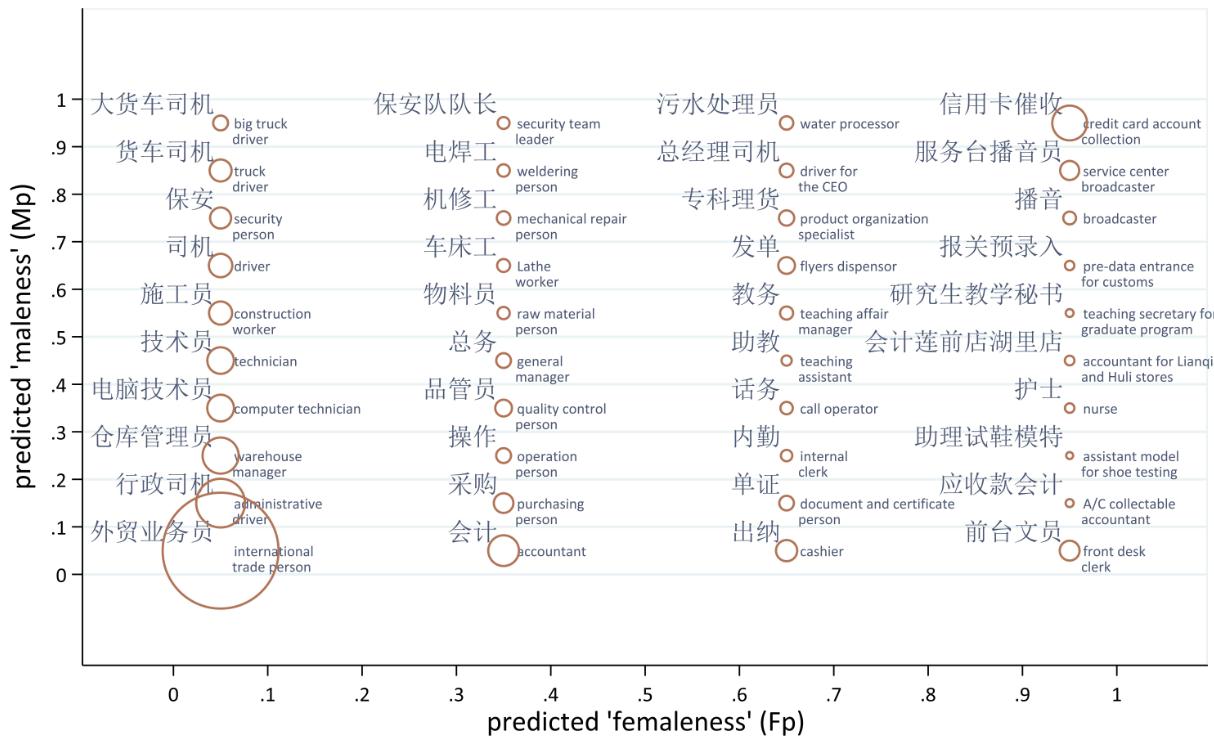

Since workers may be able to infer job ads’ implicit gender preferences from job titles, we construct indicators of the predicted, or implicit, ‘maleness’ or ‘femaleness’ of the jobs. This is done using machine learning analysis of the words in the job titles. The job titles with the most applications at different levels of predicted maleness and femaleness are presented in Figure 2. As Figure 2 shows, while “front desk clerks” and “big truck drivers” are typically female and male jobs, respectively, in this market, there are also jobs like “credit card account collection” that are often very explicit in their gender preferences but can prefer females in some postings and males in others. On the other hand, jobs like “international trade person” rarely express an explicit gender preference; thus, the predicted ‘maleness’ and ‘femaleness’ of these jobs are both very low.

Note: Symbol size is proportional to the number of unique job titles in the cell. The forty cells in the figure are defined by four predicted ‘femaleness’ ranges ([0, .1], (.3, .4), [.6, .7] and [.9, 1]) and ten predicted ‘maleness’ ranges ([0, .1], (.1, .2), through [.9, 1]).

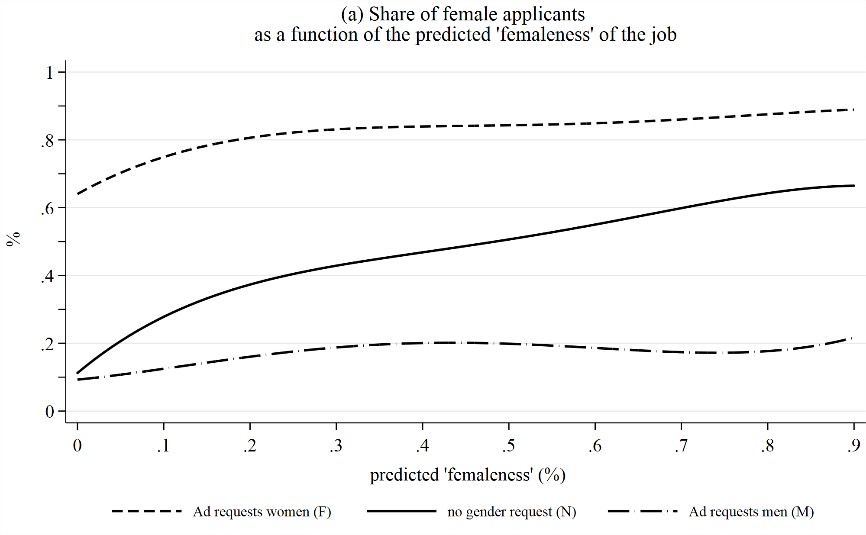

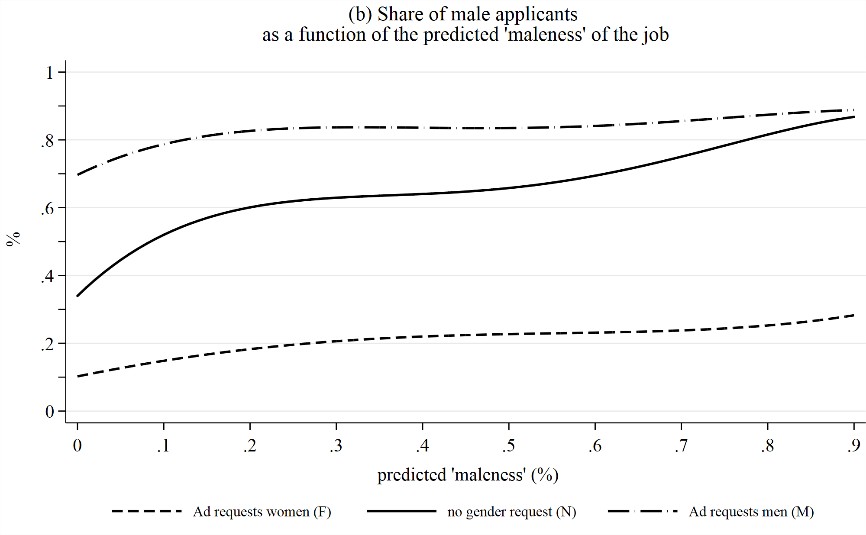

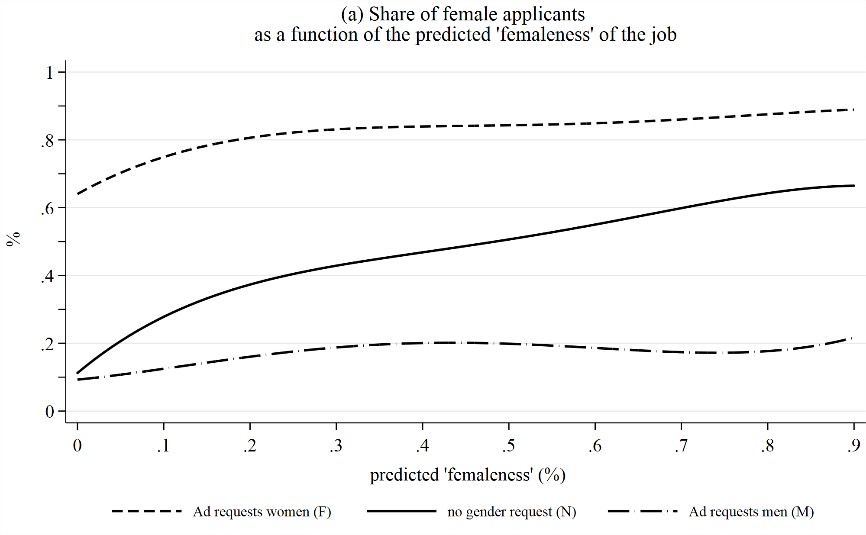

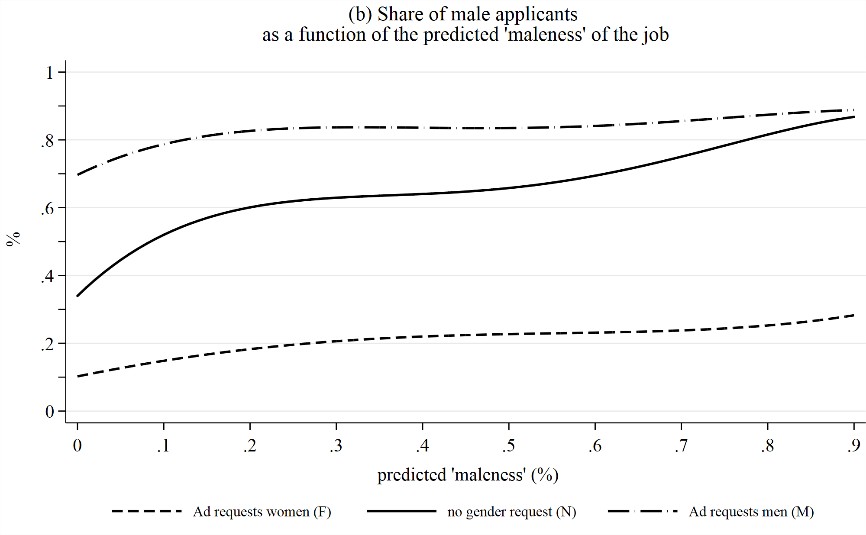

Note: This is Figure 1 of Kuhn, Shen and Zhang (2018). Here, Fp and Mp represent the predicted ‘femaleness’ or ‘maleness’ of the job ads based on job titles. F, N, and M represent job ads with explicit preference for female, none, and male workers, respectively.

These figures represent predicted values of the female (male) share of applicants from a regression of the fe(male) share of applicant on quartics in Fp and Mp and their interactions with F, N, and M. Panel (a) shows the effect of implicit femaleness (Fp) on female share of applicants, holding Mp at its mean. Panel (b) shows the effect of implicit maleness (Mp) on male share of applicants, holding Fp at its mean.

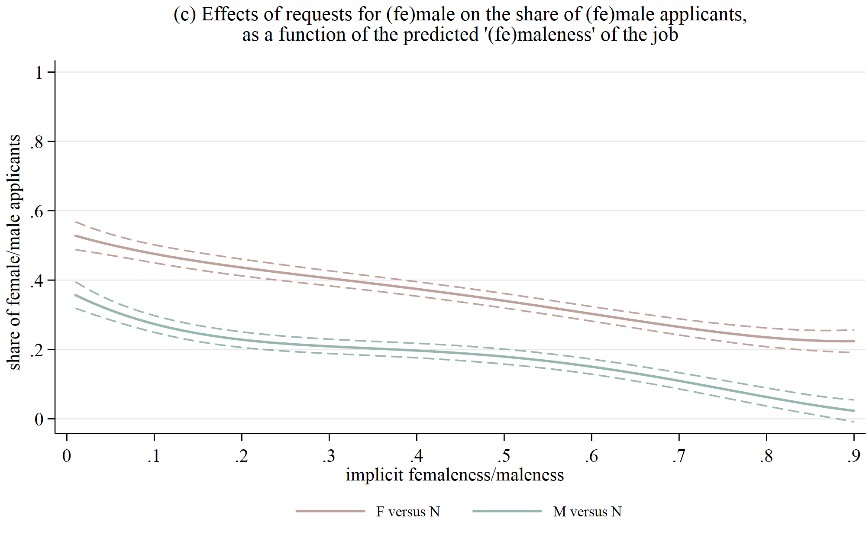

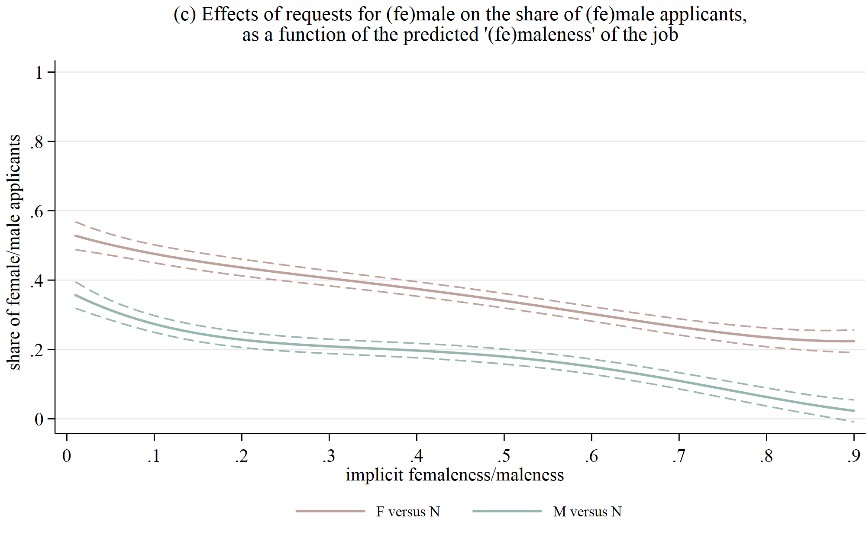

Panel (c) shows the predicted effects of attaching an explicit male (female) label to a job ad (relative to an N label) at different levels of implicit maleness (femaleness), with 95 per cent confidence bands represented by dashed lines.

By taking account of these implicit gender preference indicators, we are able to identify, arguably, the ‘pure’ impact of explicit gender preferences. As Figure 3 shows, we find that:

• Explicit gender preferences are very effective in directing workers’ application behavior [the F and M lines differ from the N lines significantly in both panel (a) and (b)].

• The impacts of job ads’ explicit gender preferences are stronger when the words in the job titles more strongly suggest the opposite gender for that type of work [the lines in panel (c) are highest when the predicted likelihood for the job to prefer the other gender is highest].

• Requesting women has a much stronger impact on the female applicant share than requesting men has on the male applicant share [the ‘F versus N’ line is higher than the ‘M versus N’ line in panel (c)]. Relatedly, women are much less likely to apply than men when jobs don’t explicitly request their gender [the ‘N’ line is much lower in panel (a) than in panel (b)].

The above results echo existing findings that female job searchers are more ambiguity-averse, more uncertainty-averse, and more responsive to affirmative action statements than men (Gee, forthcoming, Flory et al., 2015, Leibbrandt and List, 2014, and Ibanez and Reinter, 2018). Overall, our findings provide a rich set of empirical patterns which indicate how the explicit gender preferences of job ads actually affect the eventual labor market outcomes.

Policy implications

Our findings suggest the importance of directing workers to apply to certain jobs for gender equality in the labor market. Policies that target workers’ application behaviors are at least as important as policies that target employers’ screening behaviours, if not more.

Angwin, Julia, Noam Scheiber and Ariana Tobindec (2017). “Facebook Job Ads Raise Concerns About Age Discrimination,” New York Times, December 20, 2017

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/20/business/facebook-job-ads.html

Banfi, Stefano and Benjamin Villena-Roldan (forthcoming). “Do High-Wage Jobs Attract more Applicants? Directed Search Evidence from the Online Labor Market,” Journal of Labor Economics.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/702627

Blau, Francine and Lawrence Kahn (2017). “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Sources,” Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3), pp.789-865.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.20160995

Delgado Helleseter, Miguel, Peter Kuhn and Kailing Shen (forthcoming). “Age and Gender Profiling in the Chinese and Mexican Labor Markets: Evidence from Four Job Boards,” Journal of Human Resources.

http://jhr.uwpress.org/content/early/2018/10/11/jhr.55.3.0416-7836R2.full.pdf+html

Flory, Jeffrey A., Andreas Leibbrandt and John A. List (2015). “Do Competitive Workplaces Deter Female Workers? A Large-Scale Natural Field Experiment on Job Entry Decisions,” The Review of Economic Studies, 82(1), pp. 122–155.

https://academic.oup.com/restud/article/82/1/122/1545901

Gee, Laura (forthcoming). “The More You Know: Information Effects on Job Application Rates in a Large Field Experiment,” Management Science.

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2994

Goldin Claudia (2014). “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter,” American Economic Review, 104 (4), pp.1091-1119.

https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/goldin/files/goldin_aeapress_2014_1.pdf

Ibanez, Marcela and Gerhard Reinter (2018). “Sorting through Affirmative Action: Three Field Experiments in Colombia,” Journal of Labor Economics, 36(2), pp. 437-478.

https://doi.org/10.1086/694469

Kuhn, Peter and Kailing Shen (2013). “Gender Discrimination in Job Ads: Evidence from China,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1), pp.287-336.

https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjs046

Kuhn, Peter, Kailing Shen and Shuo Zhang (2018). “Gender-Targeted Job Ads in the Recruitment Process: Evidence from China,” NBER working paper, 2018, no. 25365.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w25365

Leibbrandt, Andreas and John A. List (2014). “Do Women Avoid Salary Negotiations? Evidence from a Large-Scale Natural Field Experiment,” Management Science, 61(9), pp.2016-2024.

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1994

Niederle, Muriel and Lise Vesterlund (2007). “Do Women Shy Away from Competition? Do Men Compete Too Much?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(3), 1067-1101.

Gender-targeted job ads are common in many emerging economies. This article summarizes several of our recent studies on this subject. We find that explicit gender preferences in job ads 1) favor women about as frequently as men; 2) are much less common in jobs with high skill requirements; 3) vary substantially within firms but less within jobs, and 4) ‘tilt’ strongly towards men as workers get older. Besides employers’ job posting behavior, we have also examined workers’ application behavior and employers’ call-back behavior in the presence of gendered job ads.

Using data from a Chinese job board, we find that 1) job ads’ explicit gender preferences can account for 59% of the eventual gender segregation across jobs in our data; 2) most of this gender segregation can be accounted for by gender preference-linked self-selection in the application stage; and 3) job ads’ explicit gender preferences are very effective in directing workers’ application behavior. Furthermore, the impact of explicit gender preferences is strongest when the jobs’ titles are least likely to be interpreted as preferring the applicant’s gender. Interestingly, women are much less likely to apply than men when jobs don’t explicitly request their gender. These findings suggest that policies that target workers’ application decisions are at least as important as policies that target employers’ screening decisions, if not more.

Introduction

There is a huge literature on gender discrimination and inequality in the labor market (i.e., Blau and Kahn, 2017, and Goldin, 2014). While it is undeniable that the job search and matching process plays a pivotal role in gender inequality in the labor market, there have not been many studies from the search-and-matching perspective due to data availability constraints. But the increasing usage of online job boards in the past decade has largely alleviated such constraints. We use online job board data to examine gender targeted job ads in a series of recent studies.

The practice of stating an explicit gender preference in job ads is widely used in emerging economies. In China, the earliest regulation that we are aware of that specifically prohibits gender discrimination by labor market intermediaries is the Ministry of Labor and Social Security’s Regulations on Employment Service and Employment Management issued in 2007. However, enforcement of anti-discrimination laws at that time is widely perceived to have been weak. Gendered job ads largely disappeared from national job boards only after China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology issued a regulation aimed directly at gendered job ads on online job platforms in 2016. Nonetheless, in China such ads are still common in many local and smaller job boards. On the other hand, even in countries where gender discrimination is illegal, employers are now able to limit exposure of their job ads to their preferred worker types with the help of targeted advertising (Angwin, Scheiber and Tobin, 2017). Together, these observations indicate that employers’ discriminatory behavior demands continuous attention.

When we examine the labor market at a granular level, the agents in the labor market are obviously not matched with each other randomly. Instead, employers and workers strategically search and match over time through a three-stage dynamic process. First, employers decide on the content of job ads. Then workers decide on the set of jobs for which they apply. Finally, employers decide on the set of workers to interview and hire. In this process, employers’ job posting decisions on whether or not to include an explicit gender preference in the job ads initiates the whole dynamic of gender segregation. The impacts of employers’ gender requests depend on the responsiveness of workers as well as employers’ enforcement at the screening stage.

Here, we shall summarise the main findings of our studies on explicit gender preferences in job ads in terms of patterns, impacts, and mechanisms. A brief discussion of the policy implications of our studies will conclude this article.

1. Patterns

Using job posting data from four online job boards, Kuhn and Shen (2013) and Delgado Helleseter et al. (forthcoming) establish four major patterns of employers’ explicit gender preferences:

• Symmetry: The shares of job ads that request men and women roughly equal each other.

• Negative skill-targeting: Job ads requesting less education, less experience, and offering lower wages are more likely to express a gender preference. This applies to requests both for men and for women.

• Job- (rather than firm-) specificity: Whether a job ad requests a man or a woman is more closely linked to the type of work to be done than the identity of the firm posting the ad. In fact, it is common for the same employer to request men for some jobs and women for others.

• The ‘age twist’: As the desired worker age rises between 18 and 45, employers’ advertised gender requests ‘flip’ from strongly favoring women to strongly favoring men. Figure 1 provides descriptive evidence of such age-twist patterns.

Figure 1 The Age Twist in Gender Preferences in Job Ads

To further understand the age twist in employers’ gender preferences, we use the information contained in job titles as well as nationally representative survey datasets of China and Mexico, and find that:

• 65% of the age twist can be ‘explained’ by age-related changes in the mix of tasks. In particular, employers tend to prefer young women for ‘helping’, customer contact, and administrative occupations, while preferring older men for managerial jobs.

• Employers’ preferences for young women and employers’ preferences for beauty are strongly, and positively, correlated.

• Employers’ gender-specific preferences for workers’ marital and fertility status also contribute to the age twist. Specifically, employers prefer single women and women without children, while preferring married men and men with children.

It is worth noting that the four online job boards we study—Zhaopin.com (a national job board in China), XMRC.com (a city level job board targeting white-collar jobs), XMZYJS.com (a city level job board targeting blue-collar jobs), and Computrabajo-Mexico (a national job board in Mexico)—differ substantially in terms of culture, size, and user groups targeted. Nonetheless, evidence from all four of these job boards support the above patterns.

2. Impacts and Mechanisms

Recently, our research has shifted to the second and third stages of the search and matching process. It is worth noting that workers’ application behavior and employers’ job posting and call back behavior are assumed to depend on each other in our setup. Such assumptions are supported by several empirical studies (i.e., Banfi and Villena-Roldan, 2018, and Niederle and Lise, 2007).

Specifically, Kuhn et al. (2018) examine the impacts of employers’ explicit gender preferences and the related mechanisms.

Using internal data provided by XMRC.com, they find that:

• 92.4% of applications and 94.8% of call-backs to gendered job ads are from (for) the requested gender.

• When considering all job ads (whether or not they have explicit gender preferences), 50-60% of the gender segregation among successful job applicants can be accounted for by job ads’ gender preferences.

Our decomposition exercises further suggest that most of the impact of gender preferences can be accounted for by workers’ application behavior, rather than employers’ call back behavior. While gender-mismatched applicants do suffer from substantial penalties in terms of callback chances, 74% of the observed matching between employer’s gender requests and successful applicants’ gender is due to workers’ self-selection at the application stage.

Since workers may be able to infer job ads’ implicit gender preferences from job titles, we construct indicators of the predicted, or implicit, ‘maleness’ or ‘femaleness’ of the jobs. This is done using machine learning analysis of the words in the job titles. The job titles with the most applications at different levels of predicted maleness and femaleness are presented in Figure 2. As Figure 2 shows, while “front desk clerks” and “big truck drivers” are typically female and male jobs, respectively, in this market, there are also jobs like “credit card account collection” that are often very explicit in their gender preferences but can prefer females in some postings and males in others. On the other hand, jobs like “international trade person” rarely express an explicit gender preference; thus, the predicted ‘maleness’ and ‘femaleness’ of these jobs are both very low.

Figure 2. Selected Job Titles, by Predicted ‘Maleness’ (Mp) and ‘Femaleness’(Fp)

Figure 3. Effects of Gender Requests (F and M) and Predicted Gender (Fp and Mp) on Female/Male Share of Applicants

These figures represent predicted values of the female (male) share of applicants from a regression of the fe(male) share of applicant on quartics in Fp and Mp and their interactions with F, N, and M. Panel (a) shows the effect of implicit femaleness (Fp) on female share of applicants, holding Mp at its mean. Panel (b) shows the effect of implicit maleness (Mp) on male share of applicants, holding Fp at its mean.

Panel (c) shows the predicted effects of attaching an explicit male (female) label to a job ad (relative to an N label) at different levels of implicit maleness (femaleness), with 95 per cent confidence bands represented by dashed lines.

By taking account of these implicit gender preference indicators, we are able to identify, arguably, the ‘pure’ impact of explicit gender preferences. As Figure 3 shows, we find that:

• Explicit gender preferences are very effective in directing workers’ application behavior [the F and M lines differ from the N lines significantly in both panel (a) and (b)].

• The impacts of job ads’ explicit gender preferences are stronger when the words in the job titles more strongly suggest the opposite gender for that type of work [the lines in panel (c) are highest when the predicted likelihood for the job to prefer the other gender is highest].

• Requesting women has a much stronger impact on the female applicant share than requesting men has on the male applicant share [the ‘F versus N’ line is higher than the ‘M versus N’ line in panel (c)]. Relatedly, women are much less likely to apply than men when jobs don’t explicitly request their gender [the ‘N’ line is much lower in panel (a) than in panel (b)].

The above results echo existing findings that female job searchers are more ambiguity-averse, more uncertainty-averse, and more responsive to affirmative action statements than men (Gee, forthcoming, Flory et al., 2015, Leibbrandt and List, 2014, and Ibanez and Reinter, 2018). Overall, our findings provide a rich set of empirical patterns which indicate how the explicit gender preferences of job ads actually affect the eventual labor market outcomes.

Policy implications

Our findings suggest the importance of directing workers to apply to certain jobs for gender equality in the labor market. Policies that target workers’ application behaviors are at least as important as policies that target employers’ screening behaviours, if not more.

(Peter Kuhn, Department of Economics, University of California, Santa Barbara; Kailing Shen, Research School of Economics, The Australian National University.)

Angwin, Julia, Noam Scheiber and Ariana Tobindec (2017). “Facebook Job Ads Raise Concerns About Age Discrimination,” New York Times, December 20, 2017

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/20/business/facebook-job-ads.html

Banfi, Stefano and Benjamin Villena-Roldan (forthcoming). “Do High-Wage Jobs Attract more Applicants? Directed Search Evidence from the Online Labor Market,” Journal of Labor Economics.

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/702627

Blau, Francine and Lawrence Kahn (2017). “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Sources,” Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3), pp.789-865.

https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.20160995

Delgado Helleseter, Miguel, Peter Kuhn and Kailing Shen (forthcoming). “Age and Gender Profiling in the Chinese and Mexican Labor Markets: Evidence from Four Job Boards,” Journal of Human Resources.

http://jhr.uwpress.org/content/early/2018/10/11/jhr.55.3.0416-7836R2.full.pdf+html

Flory, Jeffrey A., Andreas Leibbrandt and John A. List (2015). “Do Competitive Workplaces Deter Female Workers? A Large-Scale Natural Field Experiment on Job Entry Decisions,” The Review of Economic Studies, 82(1), pp. 122–155.

https://academic.oup.com/restud/article/82/1/122/1545901

Gee, Laura (forthcoming). “The More You Know: Information Effects on Job Application Rates in a Large Field Experiment,” Management Science.

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2994

Goldin Claudia (2014). “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter,” American Economic Review, 104 (4), pp.1091-1119.

https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/goldin/files/goldin_aeapress_2014_1.pdf

Ibanez, Marcela and Gerhard Reinter (2018). “Sorting through Affirmative Action: Three Field Experiments in Colombia,” Journal of Labor Economics, 36(2), pp. 437-478.

https://doi.org/10.1086/694469

Kuhn, Peter and Kailing Shen (2013). “Gender Discrimination in Job Ads: Evidence from China,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1), pp.287-336.

https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjs046

Kuhn, Peter, Kailing Shen and Shuo Zhang (2018). “Gender-Targeted Job Ads in the Recruitment Process: Evidence from China,” NBER working paper, 2018, no. 25365.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w25365

Leibbrandt, Andreas and John A. List (2014). “Do Women Avoid Salary Negotiations? Evidence from a Large-Scale Natural Field Experiment,” Management Science, 61(9), pp.2016-2024.

https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1994

Niederle, Muriel and Lise Vesterlund (2007). “Do Women Shy Away from Competition? Do Men Compete Too Much?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(3), 1067-1101.

https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.1067

Latest

Most Popular

- VoxChina Covid-19 Forum (Second Edition): China’s Post-Lockdown Economic Recovery VoxChina, Apr 18, 2020

- China’s Great Housing Boom Kaiji Chen, Yi Wen, Oct 11, 2017

- China’s Joint Venture Policy and the International Transfer of Technology Kun Jiang, Wolfgang Keller, Larry D. Qiu, William Ridley, Feb 06, 2019

- The Dark Side of the Chinese Fiscal Stimulus: Evidence from Local Government Debt Yi Huang, Marco Pagano, Ugo Panizza, Jun 28, 2017

- Wealth Redistribution in the Chinese Stock Market: the Role of Bubbles and Crashes Li An, Jiangze Bian, Dong Lou, Donghui Shi, Jul 01, 2020

- What Is Special about China’s Housing Boom? Edward L. Glaeser, Wei Huang, Yueran Ma, Andrei Shleifer, Jun 20, 2017

- Evaluating Risk across Chinese Housing Markets Yongheng Deng, Joseph Gyourko, Jing Wu, Aug 02, 2017

- Privatization and Productivity in China Yuyu Chen, Mitsuru Igami, Masayuki Sawada, Mo Xiao, Jan 31, 2018

- How did China Move Up the Global Value Chains? Hiau Looi Kee, Heiwai Tang, Aug 30, 2017

- China’s Shadow Banking Sector: Wealth Management Products and Issuing Banks Viral V. Acharya, Jun Qian, Zhishu Yang, Aug 09, 2017

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Instagram

Instagram WeChat

WeChat  Email

Email